Infobae’s new report delves into the football star’s last days, the apathy within his inner circle and his doctors shown through interviews, pictures and audio messages included in the investigation that seeks to determine whether he was the victim of involuntary manslaughter

On October 30, 2020, Diego Armando Maradona walked through the mouth of a plastic wolf and entered the pitch of the Juan Carmelo Zerillo stadium, located in the outskirts of La Plata, Argentina. The field was lined with cameras and reporters, but the bleachers were half-empty due to the pandemic. A rumor of chants came from the few who were present, the stadium draped in flags despticting Maradona as a hero, his silhouette and the spirit of Mexico 1986. There were argentine footballing dignitaries that day, top officials who lined up to greet him and pat his back and give him gifts of little interest to him. His last son, Dieguito Fernando, was there. Maradona turned 60 and celebrated it as Gimnasia y Esgrima de La Plata’s head coach, a local A-League team and the host of his birthday party. He was also celebrating it as a man whose end was much closer than it was perhaps supposed to. The legend that lived too much was running on too little.

While the stadium roared, an assistant held his hand through the plastic wolf’s mouth as he waded through with the pace of a little worn out man. Those who became members of his inner circle, lawyers Víctor Stinfale and Matías Morla —the men who claimed to represent his interests throughout the last decade of his life, skillful players who played a role in the last days of a man of vast fortune and vaster fame— had been the ones who entered his room to wake him up that morning. Maradona was visibly upset. His family members said he looked fed up, sad. He had drank five cans of an energy drink also had coffee that moring. Perhaps it was the only thing that could get him going.

“Can he talk coherently? If he strings two words together, it’s amazing” wondered another member of his entourage. In the stadium, he barely mumbled a few words while people patted his back and posed for selfies. He didn’t even stay until the end of his own birthday party. He left. Through it all, the flags hung at the wired fences celebrated a man that, perhaps, didn’t exist anymore. Maradona had been erased, eroded. He was a palace that was no more, as if the servants of Versailles had stolen its gold and luxury objects to an extent where it was left unrecognizable, a husk.

Ironically, his own friends had become his wolves. Something was already eating away his heart on his birthday: not a plot, not a scheme, a team of four prosecutors would later suspect, but criminal neglect. That day, perhaps, on his own birthday, Maradona began to die.

And so he did. On November 25, less a month later, shortly before noon, in a room at the San Andrés de Tigre gated community, Maradona finally passed. The most beloved man in Argentina, one of the most beloved men in the world, literally died alone, with no one at his side to comfort him and take his hand. Diego was supposed to be in house hospitalization, which aimed at helping him beat alcoholism, his latest addiction following decades of hardcore cocaine and prescription pills use. He had beaten one health crisis after another. They had hurt him, but he was still standing.

However, in this case the nurse who was in the next room had not even checked his health during the previous hours, fearful, she said, of waking him up. She would later lie about nursing him at the request of one of her bosses. There were no oxygen canisters, a defibrillator, or even a buzzer next to Maradona’s bed, so he could ring to warn his caregivers in his time of greatest suffering.

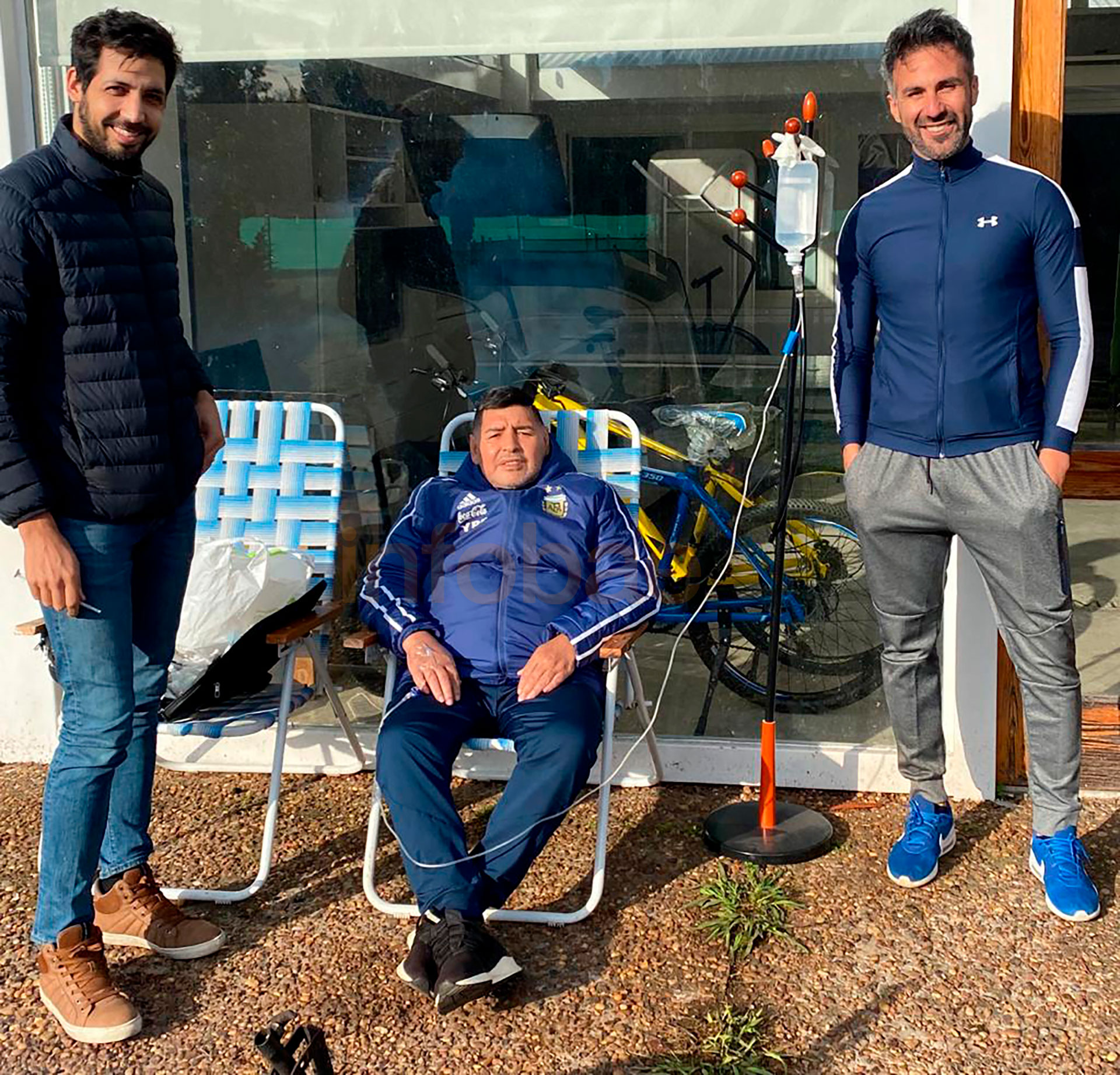

Those responsible for his health had put on a little show during the previous weeks, when Maradona underwent a brain surgery at the Olivos hospital. Neurosurgeon Leopoldo Luque and psychiatrist Agustina Cosachov faced the press and boasted about their alleged success. Luque, who did not perform the operation, had posted on his Instagram account several selfies with Maradona as if they were the best friends.

Cosachov, present that noon at the San Andrés house, couldn’t even help Maradona on his deathbed with basic CPR. Amid a hysteric situation, she was surrounded by assistants and alleged friends, an entourage who answered ultimately to Morla, Maradona’s lawyer, who years before had skilfully taken ownership of his trademark rights, the ownership of his name, one of the most coveted sports brands in the world.

Then, the world knew. And for those alleged friends, those assistants, that entourage of hangers-on, everything began to fall apart. The described circumstances of Maradona’s passing were immediately called into question by the justice system, which decided to start investigating them. Prosecutors Cosme Iribarren, Laura Capra, Patricio Ferrari, all of them led by General Prosecutor John Broyad, ordered Maradona’s body be examined in an autopsy at the San Fernando Morgue.

The coroners found out that his heart weighed more than half a kilo, an anomaly. The organ had certainly been eaten away: a cardiac insufficiency that led to a pulmonary edema was the final cause of death. But they also found scars and signs of micro-heart attacks dating back decades. Others happened right before his death. Days before, maybe hours.

Maradona had a state funeral that went chaotic. The presidential palace was taken over by fans and violent football ultras who danced meters away from the coffin, Maradona’s own family running scared while the rumor that someone or something had been criminally responsible for the idol’s death roamed the country. It was a bonafide riot. It seemed like those who went to war with the police on the streets had drunk a beverage of pain and revenge in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. The roar even frightened the president Alberto Fernández security.

The investigation continued. The posthumous drug test revealed that Cosachov had prescribed him a cocktail of psychiatric drugs: antidepressants, antipsychotics like Venlafaxine, which was clearly advised against those who suffered a heart condition like Maradona’s, diagnosed years before. His kidneys were failing. His liver was damaged by cirrhosis.

The results of the autopsy and the general lack of medical equipment at Maradona’s final home created suspicion among the prosecutors. Those who loved Maradona when he was alive and appeared before the San Isidro court as damaged parties felt the same way. Diego Fernando, Maradona’s youngest son, had Mario Baudry as his lawyer, also Dalma and Gianinna arrived to the court with their own attorney. Argentina’s greatest idol could have been the victim of involuntary manslaughter, of medical malpractice, a crime caused by negligence or omission. Consequently, the homes and offices of Luque and Cosachov were raided, their phones seized.

Those phones were cracked open by forensic experts, who extracted and analyzed their content. They had months’ worth of WhatsApp audio messages and chats with friends and strangers.

The pettiness the conversations revealed is overwhelming: it is a tale that explains Maradona’s death.

The apathy and self-interest of those who surrounded him, their only care for a place at the right side of the Father, even if it was just a selfie while his state decayed in plain sight.

Those tales, those intimate messages, which have not been exposed until now, are at the heart of this documentary. It is, ultimately, not only about Maradona: it is the secret story behind the death of Argentina’s very own heart.