A moment is enough to mark a person's life, especially that of an artist. For Joel-Peter Witkin, that moment occurred when he was very young, an episode that was definitive to turn his work towards the macabre, since it was his first encounter with the grotesque of death, but also with the naturalness inherent in it.

It happened on a Sunday morning, when he and his mother and twin brother Jerome were preparing to go to church. They were going down the stairs of the tenancy where they lived and shortly before reaching the door to leave the building, a thunderous noise was heard in the street.

There had been an incredible collision outside, three cars had collided with each other, all with families inside. The noise of pain was deafening and mixed with the cries for help of terrified victims and passers-by. Suddenly, little Joel found himself standing on the sidewalk alone and his attention was focused on something rolling out of one of the overturned cars. The strange object stopped right at her feet, it was the head of a girl. Joel bent down to touch the face that looked at him, but just before he could do it, someone took him away.

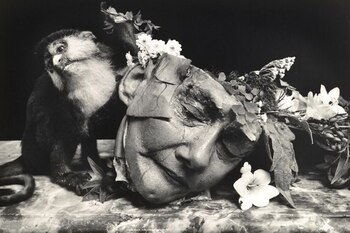

This image of a decapitated head would later be reinterpreted in his work, one of the most interesting and controversial in Western photography, which, far from adhering to aesthetic ideas popularly associated with beauty, explores the other side of the coin, ugliness as a means of artistic expression, the grotesque as an aesthetic exaltation , the abnormal, deformed, and mundane as a vindication of beautiful humanistic naturalism.

Although his artistic commitment has not been far removed from criticism, or even censorship, Joel-Peter Witkin's legacy has found ways to transcend time and make a presence in everyday life. His photographs of corpses, deformed or mutilated people, dwarves, transsexuals or hermaphrodites, usually accompanied by maximalist settings, have created a powerful aesthetic language that is impossible to go unnoticed, and which has undoubtedly influenced the cinematic language of modern horror appreciable in films such as Hereditary or Midsommar by American filmmaker Ari Aster.

A life linked to death

Joel-Peter Witkin was born on September 13, 1939 in Brooklyn, New York to a family consisting of a Jewish father and a Catholic mother, a cultural and religious difference that would end up being insurmountable and would lead the couple to divorce in a bad way.

The separation from his parents at a young age sent Joel to spend much of his childhood with his grandmother, whom he remembers with great affection. She suffered for years a gangrene on her leg that ended up causing her to lose her limb, in another key episode reported by the photographer, as she says that this caused him to associate love with the smell of putrefaction and clotted blood.

During the 1950s, at the age of 17, he bought his first camera and began to fall in love with the art of photography. He taught himself how to use it, discovering its technique and capturing with it the sad and macabre vision of life he had acquired during his childhood.

His first photos were of a rabbi who claimed he could talk to God, and a “freak show” that took place on Coney Island, which his brother Jerome asked him to portray to use as inspiration for his paintings.

Jerome, Joel's twin, is an artist of his own account, who opted for painting to deal with the demons that from an early age he shared with his brother.

In 1960 the United States Army recruited Joel during the Vietnam War, where he went as a photographer and where he could see, again, the harshness of death up close. There he would finish defining his style, dedicating himself almost exclusively to portraying the bodies of soldiers who committed suicide or died during training exercises, and thus embracing his fascination with bodies, living or dead, and the real or symbolic violence that is exerted on them.

Starting in 1967, after returning from the war, he became a freelance photographer and would continue to explore more and more in the macabre and techniques that would lead him to create shocking and dark images.

The beauty of horrible and macabre eroticism

“For me, extreme things are like miracles.” This phrase by Witkin could perfectly sum up his work, because seeing one of his photographs inevitably means entering a dreamlike and disturbing world, almost a nightmare, in which incredibly beauty appears in a striking way.

From the technical point of view, the photographer prefers the analogous processes used to produce the first daguerreotypes and ambrotypes, since these allow him to mistreat negatives, intentionally producing imperfections in the image, such as scratches, scratches or scratches, giving photos characteristic effects that amplify character violent nature of the composition and contribute a certain historical aspect, as if they were actually taken at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

On the subject, Witkin focuses on bodies, but on those bodies that we could describe as marginal or imperfect. Mutilated people, dwarves, hermaphrodites or transsexuals, often star in Witkin's photographs, which use the imperfections of their models to recreate works of art, or the styles of other artists that are a marked influence of the photographer.

Artists such as Velázquez, Giotto, Pablo Picasso or Joan Miró can be cited as influences on Witkin's work. But he also recreates works by Courbet, Seurat and Dali in his photographic paintings and some of his compositions, such as “Fetishista de Negre”, are a direct recreation of studies carried out by other photographers, with fetishistic details inserted.

But the most controversial part of his art is working with corpses, which he says he takes out of morgues in a completely legal process, which he manipulates to create striking images of a strong visual charge.

In one of his best-known photos, the one called “The Kiss”, he used a decapitated head that was cut in half in a morgue, and then inverted to give the appearance of two men who kiss.

For this type of photo, the term exploiter has been used several times against Witkin, and his work has suffered censorship in museums and exhibitions in several countries around the world. He has also been criticized for using dead animals for his works and compositions.

But Witkin's work goes far beyond the subject of death and physical deformations. Their models are very beautiful or clearly deformed and what they express with their poses evokes everything from the morbid to the erotic.

Another famous work, the so-called King Woman (1997), depicts an exceptionally tall and obese woman dressed and posed as king of some imaginary tribe. In another work called Abundancia (1997), he portrays a woman without legs or arms placed in an urn, while her head is covered with a variety of decorative elements, such as flowers and pearls. This woman symbolizes a horn of abundance, which is a term that originates in classical antiquity and evokes abundance and sustenance.

However, mortality and its issues are still considered by Witkin as the central idea of his creations, the basic skeleton of his work, which draws on sources that transcend painting and photography and mix history, literature, mythology or religion to create a surreal and horrifying fusion that many people encounter difficult to digest.

That is why the work of this photographer is provocative to the point of not leaving anyone indifferent who comes across it. In its essence, it raises moral and human questions, exacerbating the oddities of the body, corpses and its models to the point of creating a deeply spiritual and transcendent experience with its photography.

Sex is another of his major themes, as stated by the Mexican painter and art critic Francisco Soriano in an analysis of Witkin's work published on his youtube channel.

“Wilkin's photography moves between taboo subjects such as death, incest, sadomasochism and other variants of extreme sex,” says Soriano.

The critic also highlights the American photographer's vindication of ugliness. A bet that is fascinating today, finding this aesthetic of the grotesque spread not only in photography but also in cinema, theater or performative art.

This is why he explains the success of Witkin, who despite strong criticism, accusations of exploiter, abuser of animals, and censorship of his work, has gained wide international recognition by showing his work in important galleries and museums such as the Brooklyn Museum in New York, Interkamera in Prague, Picture Photo Space in Osaka, Japan and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

“Peter Witkin handles himself in a symbolic and metaphorical field that we cannot strip him of. No matter how hard we try to normalize his work, it cannot be normalized because this would imply that we have understood the taboos of all times and of all societies and do not understand them”, emphasizes the critic.

Therefore, he says, Witkin is an author who works on the boundary of what we cannot understand, the fine line between life and death, between the beautiful and the horrible, between beauty and ugliness, between the erotic and the morbid, and this is the great importance of his photography.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs