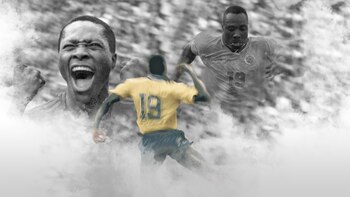

“I was born in Bonaventure on August 14, 1966. I played in Santa Fe and America, 287 games, 76 goals. I performed in Naples in Italy, Real Madrid in Spain, Palmeiras, Corinthians, Santos and Cruzeiro in Brazil (...) I never lowered my arms.” It is Holy Thursday, I return today to the words that Freddy Rincón wrote in Volume 1 of the History of the Colombian National Team, by Guillermo Ruíz Bonilla. A few days ago, the 'morocho', as 'El Pibe' Valderrama called him, had an accident in his car, in Cali. He was driving very early and at an unsuspecting crossing, a bus took him in front of him. He was taken to the headquarters of the Imbanaco Clinic and quickly, after determining that he had suffered severe head trauma, he was operated on. The news began to be filled with reports about it. “This is the state of the former footballer”, “This is how the recovery of Freddy Rincón progresses”, “The condition in which the former Real Madrid player is very serious”, “Strength, Freddy, the message of Colombians to the former footballer”, “Up old, we need you”, “The state of Freddy Rincón continues to worsen”. There was no need to search for the word “Freddy” on Google, when all the news and newspaper updates already had something to say about it. Radio, television, all the press, and almost the country thought of only one thing, uttered only one name: Freddy Rincón.

A few hours after the last medical report, on April 13, 2022, the news of the death of 'El Colosso' was reported. Then, the noise was extinguished. It was inevitable to think of something else. More than one felt inside that something was breaking. More than one cried, grieved, sunk in pain, in the lament of having lost something with the subtlety of a sigh. Perhaps, for my generation and those that followed, the tragic event had no greater reception, but for that of my parents and theirs, this wound is deep.

The first time I heard about Freddy Rincón was because of my dad. Football is the only language in which my old man and I understand each other, and from a very young age he taught it to me. He told me about Millionaires and the great players of the time, about Di Stéfano and Pedernera, about Gambeta Estrada, Blessed Fajardo and old Willy, about Valderrama and Asprilla, about Rincon and Madrid, Rincon and Naples, Rincon and Brazil. For me, he was the brightest player. I could never see him play, not live, but from what my dad told me and from the videos, photos, interviews, I knew he was one of the greatest, that he will always be.

Everyone is talking about that goal he scored against Germany, and of course, there is no other that erices the skin so much. That goal, for the Colombians, is like for the Argentines that of Maradona to the English. There is so much poetry at that moment, so much history. Thirty-two years have passed and chronicles are still written about it, sketches, entire books. Eduardo Galeano once described it, in a few words, in his Football to Sol y Sombra:

Alberto Galvis, in a chronicle that is part of his book Deportivas de Colombia, described it as the most important episode of Colombian football and quotes Francisco Maturana, who at the time said that Rincón's goal had been “a breath of faith and hope.” Nobody forgets the passionate story of William Vinasco. It is that emotion that transmits, I think, that ends up touching those of us who, years later, continue to watch the videos of that wonderful goal. “Colombia is coming, my God. Colombia is coming! I don't think there is another narrative of a match that we have learned by heart, nor any with such magnetism.

Rincón himself described his goal in Ruíz Bonilla's book: “I remember the play. Recovers Leonel Álvarez who passes the ball to Fajardo, again receives Valderrama who puts a deep pass so that I can get there and beat the German goalkeeper through the legs. Goal! It was one of the happiest moments of my life.” Not just his life, I'm sure, but of so many others. “That goal lifted the country,” my mother once told me, who although not a football player, treasures great moments. “All the kids wanted to be like Freddy Rincon.” And of course, who would not have wanted to be like 'El Colosso', nicknamed after journalist Mario Alfonso Escobar. It is that he was a brunette almost two meters tall who ran like gazelles and scored goals with tremendous coldness and strength, who had reached the most important team in the world and went on to win Pelé's 10 at Santos.

Rincón was part of the so-called “Golden Generation” of our football. If you looked in the old world cup albums, there was your picture. My uncle had some saved and I was always looking for the page where Colombia was, and there was the morocho, who managed to play in three world championships with the National Team and score Argentina in 5-0. If even figurines with his face and dolls had. Rincón was the superhero in the 90s, and he will remain so for a long time, because we haven't figured out how to kill superheroes yet.

'El Colosso' began his career as a footballer in an amateur team from Buenaventura. The coaches of that time were not interested in getting there and that's why they couldn't see it before. Wilson Díaz, who worked in customs, proposed to Rafael Pachón that he take some players to Bogotá to try them out. They chose four: Juan Reyes, Carlos Potes, Edison Cuero and Freddy Rincón. That's where it all started, although on the way there was more than one stumbling block. It was the year of 1986. The player joined the inferior players of Independiente Santa Fe and there he played his first reserve matches. He made his first team debut against Junior from Barranquilla, under the command of Jorge Luis Pinto.

In his first game, Rincon scored two goals. That's when they knew I was called to do big things. He won a title with the cardinals in 1989 and that was enough. It was the first title the team won after 13 years of drought. That's when they saw him from the America of Cali and he left. Rather than being part of the team, he decided to join the Red Devils by returning to their homeland. In Bogotá I had to experience difficult episodes. He arrived to be led by Gabriel Ochoa Uribe and surprised in the Copa Libertadores in 92, scoring several goals. Then, Boca Juniors from Argentina asked about him, but it was from Brazil that the most concrete proposal came. He ended up joining Palmeiras in the year I was born, the same year in which Colombia played the United States World Cup and Andrés Escobar was killed.

His fast and stylized play allowed him to surprise and quickly fit into Brazilian football, where he would spend several years and where he would return several times throughout his career. With Palmeiras he won two titles and became the first Colombian player to score in the Brazilian tournament. His time at the club did not last long, but it was enough to leave his name printed on its history. Then came the dream of playing in Europe. Freddy Rincón was signed by Napoli, the legendary team that had achieved everything with Diego Armando Maradona as their top reference.

It is a pity that Rincon was not able to succeed in Italy as expected. However, his good football, regardless of the obstacles, ended up being imposed on more than one occasion and this allowed him to be watched from Spain. In Seria A, the Colombian played 27 games and scored 7 goals. He did not win any title and his relationship with the fans was not the best. Several episodes of racism ended up causing him to gradually move away from the team and the city. Like a lifesaver, Real Madrid's offer came.

His performances at Calcio aroused the interest of meringues. Jorge Valdano was the one who suggested to the board of the white club that they sign him. In 1995, Freddy Eusebio Rincón became the first Colombian to wear the Real Madrid shirt. He was also the first national footballer to participate in the Champions League. At first, it seemed as if his arrival was ready for everything to work out, but he did not manage to adapt easily to Spanish football and with the team's poor performance, coach Valdano, who trusted him, was dismissed. With the arrival of Arsenio Iglesias Pardo to technical management, the Colombian understood that his time with the Spanish club was coming to an end. He only participated in 21 matches and scored 1 goal.

In mid-1996 he returned to Brazil and after a short time at Palmeiras, he signed for Corinthians, a team where, today, he is fondly remembered. He won several titles, including the Club World Cup, and was captain for several years. In 2000 he went to Santos and he is there for a while. In 2001 he joined Cruzeiro and, amid controversies over bad business off the court, he was with the team until 2004, when he returned to Corinthians and ended his sports career there.

The thing about Rincón in Brazil was so good that, in the years after his time in European football, Lorenzo Sanz, president of Real Madrid, traveled to Brazil in the spirit of watching players who could join the white team, but returned without making any offers, saying that there was no doubt that the best player in the league was Freddy Rincon, and he had already been on the team. What would have happened if the Colombian had a second cycle with meringues? I would be more of a Madrid fan than I am today. It is a pity that time itself has been turned against him, as if it were a divine punishment. As if the gods were envious.

Rincón is remembered for having been present in several of the most important episodes of Colombian football, but I am interested in remembering him as the man who aroused the most emotions in the country with his mere existence, who made me shudder, even though I saw him on a recording that had been going on for years. He died, but only in body. Rincón is and will always be one of those winged humans who are sent to earth to balance the lives of us worldly people. His way of running on the field, of carrying the ball by his feet, was the dance of a fallen angel sentenced to face men who did not deserve to enjoy his presence. Rincón was the joy of a country, its sadness, its pain. It was the rise and fall, the dream and the nightmare. It is the legend of those times that were already, where there was talk of the life that arose behind a ball, and it was beautiful, like poetry.

That's the story my father told me, the story of Bonaventure's 'The Colossus'.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs