Coronavirus can infect specialized cells that keep the heart rhythm. Altering them can trigger a process of self-destruction within cells and generate arrhythmias, according to a study preclinical co-led by researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian and the NYU Grossman School of Medicine. The results offer a possible explanation for the cardiac arrhythmias commonly seen in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The study was published in the specialized journal Circulation Research of the American Heart Association. The researchers used an animal model and human cells derived from stem cells to demonstrate that the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus can easily infect cells that are the heart's natural pacemaker and make up the so-called “sinus or sinoatrial node”.

They are a group of specialized cells, located in the upper part of the right atrium, that produce electrical impulses that spread through the heart up to reaching the ventricular muscle and stimulating the contraction of the heart. This organ of the human body pumps almost 5 liters of blood through the body per minute. Even at rest, the heart beats (dilates and contracts) between 60 and 80 times a minute.

It is known that in some people, arrhythmias are a congenital defect, that is, they are born with this problem. Some diseases, high blood pressure and hemochromatosis (accumulation of iron in the body), can contribute to arrhythmias. In addition, stress, caffeine, tobacco, alcohol, and some over-the-counter cough and cold medicines can affect the natural rhythm of the heartbeat.

The new research was developed by scientists from the Weill Cornell Medicine institution in the United States. The results amazed the experts. “This is a surprising and seemingly unique vulnerability of these cells: we have studied other types of human cells that can be infected by the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, including heart muscle cells, but we have only found signs of ferroptosis in pacemaker cells,” he says Dr. Shuibing Chen, co-author of the study and professor of chemical biology in surgery and chemical biology in biochemistry at Weill Cornell Medicine.

What they found is that if a person catches the coronavirus and develops the infection, it can trigger a process called “ferroptosis”, in which cells self-destruct but they also produce reactive oxygen molecules that can affect nearby cells.

Cases of arrhythmias including heart rhythms that are too fast (tachycardia) and too slow (bradycardia) have previously been observed among many COVID-19 patients, and multiple studies have linked these abnormal rhythms to worse COVID-19 outcomes. However, it was not clear how coronavirus infection could cause these arrhythmias.

In the new study, researchers, including Dr. Benjamin TeNoever, who is part of New York University's Grossman School of Medicine, examined golden hamsters - one of the only laboratory animals that reliably develop COVID-like signs. 19 due to the coronavirus. They found evidence that, following nasal exposure, the virus can infect the cells of the natural cardiac pacemaker unit, known as the sinoatrial node.

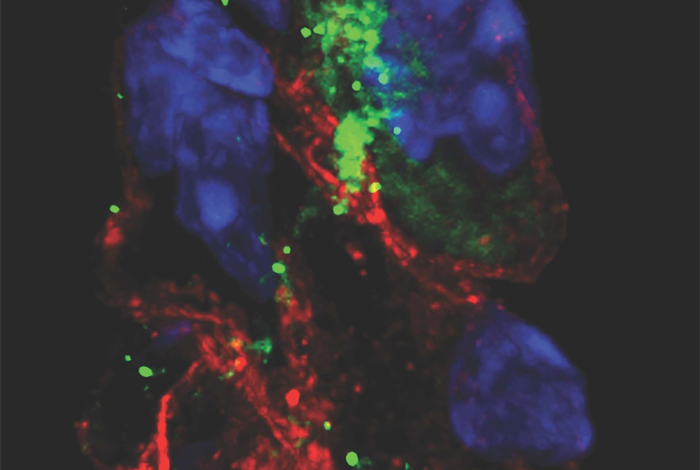

To study the effects of coronavirus on pacemaker cells in more detail and with human cells, the researchers used advanced stem cell techniques to induce the maturation of human embryonic stem cells into cells much like those of the sinoatrial node.

They demonstrated that these induced human pacemaker cells express the ACE2 receptor and other factors that the coronavirus uses to enter cells and are easily infected. Researchers also observed a large increase in the activity of inflammatory immune genes in infected cells.

However, the team's most surprising finding was that pacemaker cells, in response to the stress of infection, showed clear signs of a process of cellular self-destruction called “ferroptosis”. That process involves iron accumulation and the unbridled production of reactive oxygen molecules that destroy cells. Scientists managed to reverse these signs in cells using compounds known to bind iron and inhibit ferroptosis.

“This finding suggests that some of the cardiac arrhythmias detected in patients with COVID-19 could be caused by damage to the sinoatrial node caused by ferroptosis,” says Dr. Robert Schwartz, co-author of the study, associate professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Weill Cornell Medicine and hepatologist at the NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Although in principle patients with COVID-19 could be treated with ferroptosis inhibitors specifically to protect the cells of the sinoatrial node, antiviral drugs that block the effects of infection on all cell types would be preferable, the researchers said. Researchers plan to continue using their cellular and animal models to investigate sinoatrial node damage in COVID-19.

“There are other syndromes of sinoatrial arrhythmia in humans that we could model with our platform,” said Dr. Todd Evans, another co-author of the study, Peter I. Pressman professor of surgery and associate dean of research at Weill Cornell Medicine. “And while doctors can now use an artificial electronic pacemaker to replace the function of a damaged sinoatrial node, there is the potential here to use sinoatrial cells like the ones we have developed as an alternative, cell-based pacemaker therapy.”

Consulted by Infobae, cardiologist Mario Boskis, from the Argentine Society of Cardiology, commented: “The new study carried out in the United States helps us understand a little more the ability of coronavirus to generate arrhythmias. By infecting the sinus node, the “generating” center of our heart rhythm, the coronavirus could be responsible for inducing significant damage to its cellular architecture. That results in a decrease in heart rate or bradycardia.”

Regarding possible treatments, Dr. Boskis said: “If the arrhythmia is very severe, the treatment is the implantation of a cardiac pacemaker. The use of drugs such as deferoxamine or Imatinib demonstrated in this study in cell cultures that they could have a protective effect on the sino-atrial node, but it remains to be demonstrated whether this effect is true in patients. For now, attention should be paid in patients with Covid, to the generation of arrhythmias that can be potentially malignant, for example in cases that trigger inflammatory myocarditis”.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs