In Guayaquil, an Ecuadorian city known for its high rates of violence, a particular figure painted on the walls caused panic among its inhabitants. Several pigs — as pigs are called in some Latin American countries — appeared spray-painted on the walls of the city and on the road to Samborondón, a city a few minutes from Guayaquil, known for housing the upper class of that coastal area. The pigs had different colors and, apparently, have a macabre meaning. It was December 2004 when the “chanchocracy” terrorized the port city.

Almost two months after being fired from a job, Daniel Adum, a “sinceptual” artist (with no concept), as he defines himself, received an email announcing a tragedy: “It is said that two of the leaders of these Latin Kings youth gangs have been murdered in Spain. It seems that the murderer is an upper-class Guayaquilean. The fact is that members of this band have come from Spain and have joined with those who were already here and it is rumored that they will retaliate against four hundred Guayaquileans: two hundred for each dead”. The message, which was reproduced as a mail chain — something very typical from the beginning of 2000 — referred to pigs spray-painted on the walls of Guayaquil. The mail assured that these figures were a macabre message from the Latin Kings.

The Latin Kings, a street gang that started in the United States, but that replicated in several countries, especially in the 1990s. In Ecuador and Spain there was news about his misdeeds. In Guayaquil, they were the criminal gang responsible for robberies, murders and assaults. The Latin Kings were at odds with the Ñetas, according to the press in early 2000. Los Ñetas are an armed band originally founded at the Rio Piedras State Penitentiary in Puerto Rico, after several mutinies within different penal institutions. They arrived in Ecuador during the 2000s, accompanied by Los Latin King.

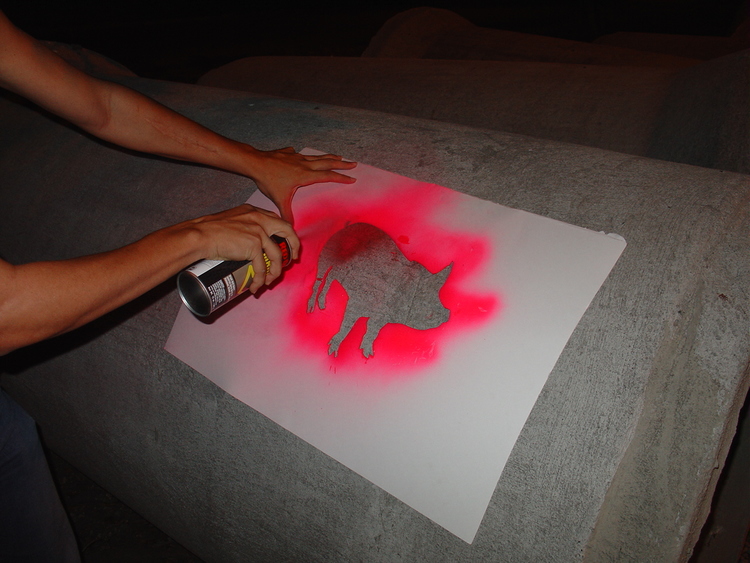

With this background, the email warning about the terrible meaning of spray pigs alarmed everyone who received it. The message detailed that the colors of each pig meant something. The black pigs were synonymous with death, the red ones announced rape and the whites were a reference to “fright” or fear, meaning that the object was to “scare them”. As gang expert and peace activist Nelsa Curbelo explained to Radio Ambulante, the way gangs communicate is through graffiti and not stencils — a technique that uses a template to make figures on various surfaces. Despite this, the press, the authorities and citizens took the mail for a real warning.

Adum, who decided to paint pigs on the walls after being fired to practice his stencil technique, could not believe his reading. He knew that spray pigs painted on the walls were an experiment that he started, a couple of months earlier, seconded by his girlfriend, who accompanied him to paint them. At that time, Adum was only 25 years old and had already achieved something that many artists take years to do: his work was commented on by everyone, although the meaning they had attributed to it was completely wrong.

There were 30 pigs painted, especially on the road to Samborondón. The media, knowing the supposed meaning of the pigs, began to report on the threat, even the city authorities and the police gave statements trying to calm citizens, they said that there was already a plan to preserve the safety of children and adolescents, that there was a ongoing research. The police gave security talks and to keep calm in schools and colleges.

As expected, parents who knew about the alleged murderous message of spray pigs prevented their children from being alone at parties, malls and other public places. The teenagers of that time were afraid and every time they saw one of the pigs they became alert. Adum, who preferred not to watch television or watch newspapers, was not aware that the city lived in fear because of the pigs he had painted.

The collective hysteria was progressing and Adum didn't know it. One day — as Adum tells on the NPR podcast — the young artist received a call from a journalist from the newspaper El Universo, one of Ecuador's largest and most important newspapers. The journalist asked him to confess that he had painted the pigs, that he had information that made him responsible for the paintings. Adum only said that he did know about the author of the art project and that speculations around the pigs were wrong. Despite this, the next day, on the front page, El Universo told the news that was already known to everyone: the Latin Kings sent a macabre message through 30 pigs painted in Guayaquil. Once again, Adum, at the age of 25, achieved something unexpected: news of his work was the headline of one of the most important media in Ecuador.

An aunt from Adum worked in the Municipality of Guayaquil. She called her nephew and asked him for information about the pigs. In the conversation he told him that if he was responsible they would be lenient, that he should only delete them and pay a fine of $100. Adum told him everything and, as they agreed with his aunt, he went to the Municipality to pay the fine and then a cameraman and a lawyer from the council accompanied him to delete the pigs that frightened the whole city. The media learned of the author's identity, through an official mayoral bulletin, and began asking Adum for interviews. The young artist took advantage of his media visibility to give his work a more transcendent meaning and called it the “Chanchocracy”.

According to the official website of Adum, the Chanchocracy “contains the classism, fear and irresponsibility of Guayaquil society. On the surface it is just a bunch of pigs loose in Guayaquil, but its interior preserves the most filthy essence of society and its successful model. If at one point in my life I was interested in disturbing public order or generating some kind of collective paranoia, the stupid idea of painting pigs on walls would never have occurred to me.”

Chanchocracy was also a form of demand for politicians' propaganda. Adum told Radio Ambulante that: “If they can get to the city during election time and wallpaper the city, paint murals, put stickers on your cars without asking your permission, do whatever they want. I can also go out as a citizen and paint my pigs and... or whatever I want.”

Adum told Infobae that the Chanchocracy is still in force. For the artist, the discourse of the status quo of political parties continues to be installed in the minds of Guayaquileans: “They continue to stumble upon the same stone and continue to believe the same stories,” he says.

Although almost 20 years have passed since the Adum experiment, the Chanchocracy and the collective chaos it generated have been reflected in several reports, in a documentary and Adum himself has written a book where he tells the details of his work. From that experiment by a young unemployed artist who terrorized all of Guayaquil.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies