Global warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions has increased the temperature of the planet in recent years, and these alterations affect flora and fauna. Many bird species are nesting and laying eggs almost a month earlier than 100 years ago, according to a new study published in the journal Journal of Animal Ecology.

By comparing recent observations with centuries-old eggs preserved in museum collections, scientists were able to determine that about one-third of bird species nesting in Chicago have advanced egg laying by an average of 25 days. And as far as researchers can tell, the culprit for this is climate change.

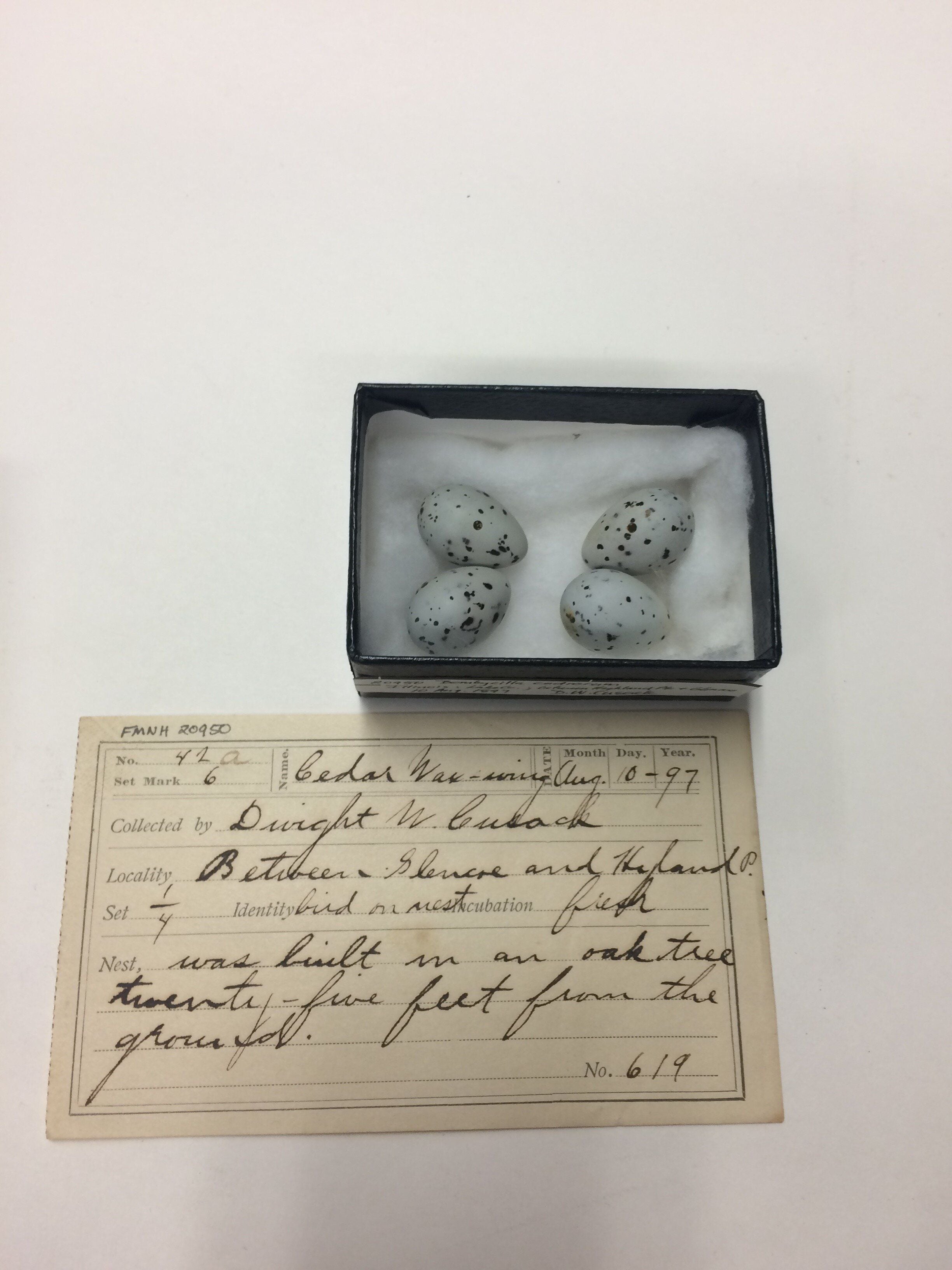

“Egg collections are a fascinating tool for us to learn about bird ecology over time,” said John Bates, bird curator at the Field Museum, in the US, and lead author of the study. “This paper combines older and more modern datasets to observe these trends for approximately 120 years and help answer really critical questions about how climate change is affecting birds,” the researcher added.

The Field Museum's egg collection occupies a small room filled with floor-to-ceiling cabinets, each containing hundreds of eggs, most of which were collected a century ago. The eggs themselves (or rather, just their shells clean and dry, with the contents flown a hundred years ago) are stored in small boxes and are accompanied by labels, often written by hand, which tell what kind of bird they belong to, where they were and precisely when they were collected, until the day.

The Field Museum's collection of bird eggs, like most, falls after the 1920s, when egg collection went out of fashion, both for amateurs and scientists. But a colleague of Bates, Bill Strausberger, had worked for years on the parasitism of thrush at the Morton Arboretum in suburban Chicago, climbing stairs and examining nests to see where brown-headed thrush had laid their eggs for other birds to breed. Thus, they were able to collect data from 1990 to 2015.

The researchers analyzed two large sets of nesting data: one from approximately 1880-1920 and another from approximately 1990 to 2015. The analyses showed a surprising trend: among the 72 species for which historical and modern data were available in the Chicago region, about a third were nesting earlier and earlier. Among the birds whose nesting habits changed, they were laying their first eggs 25,1 days earlier than a hundred years ago.

In addition to illustrating that birds are laying eggs earlier, the researchers looked for a reason. Since the climate crisis has dramatically affected so many aspects of biology, the researchers considered rising temperatures as a possible explanation for early nesting. But scientists found another drawback: there are no consistent temperature data for the region dating back to that time. So, they resorted to an indicator of temperature - the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over time is clearly mapped into larger temperature trends, and the researchers found that it also correlated with changes in egg-laying dates. “Global climate change has not been linear during this period of nearly 150 years and, therefore, species may not have advanced their date of implementation in a non-linear manner as well. Therefore, we include both linear and non-linear trends in our model,” Fidino explained.

The temperature changes are apparently small, only a few degrees, but these small changes result in the flowering of different plants and the appearance of insects, things that could affect the food available to birds.

“Most of the birds we watch eat insects, and the seasonal behavior of insects is also affected by the weather. Birds have to change their egg-laying dates to adapt,” the researchers concluded.

And although birds that lay their eggs a few weeks earlier may seem like a minor issue in the grand scheme of things, scientists point out that it is part of a larger story. “The birds in our study area, more than 150 species, have different evolutionary histories and different breeding biologies, so it's all about the details. These changes in nesting dates could cause them to compete for food and resources in ways they didn't.”

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs