Undoubtedly, one of the most recognized presidents in Mexico is Benito Juárez, who ruled in the second half of the 19th century, and who was in charge of facing the Second French Intervention and the Second Empire of Mexico, in charge of Austrian Emperor Maximilian of Habsburg and his wife Charlotte of Belgium.

Juarez also fought the Conservatives in the War of Reform, known as the Three-Years' War. In addition, from a very young age he was orphaned by parents, and he was left in charge of one of his uncles, who pushed him to get ahead. For this and more, Benito Juárez is one of the most recognized Mexican presidents in the country, and even in the world.

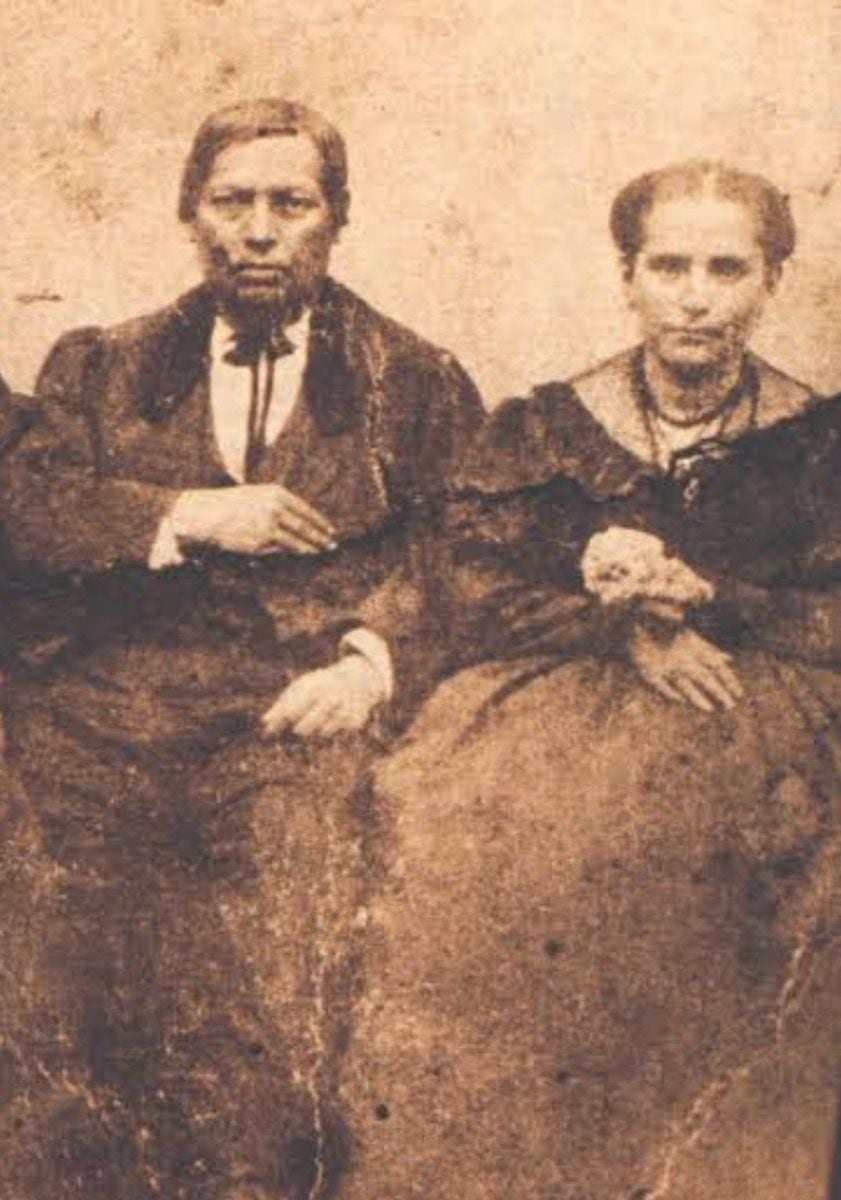

However, little is known about the woman who shared much of her life with him. Margarita Maza Parada was Benito Juarez's wife, and she was married to him for 28 years.

Margarita Maza was born on March 29, 1826, in the city of Oaxaca. She was the adopted daughter of Antonio Maza Padilla and Petra Parada, who welcomed her at birth and raised her without distinction, as the younger sister of the family. He had a childhood in a comfortable and refined home, in which his education was encouraged, which always showed solidarity with those who had the least. By 1819, the Maza Padilla family also took in Benito Juárez, a Zapotec boy just 12 years old who arrived at their home, where his sister served.

They married on July 31, 1843, when she was just 17 years old, and he was 37, with an age difference that was common in marriages of that time.

Throughout their lives, both experienced the highest moments in Mexican history, such as the war against the United States, the Ayutla Revolution, the Reformation War, the Second French Intervention and the Second Empire of Mexico. The couple had a total of twelve children: nine women and three men. However, five of them (three women and two men) died when they were young.

Throughout her life alongside Juárez, Margarita developed her liberal ideology and anticlericalism. He had great intelligence, initiative and a determined character, and was able to give political advice to the Merciful of the Americas in his struggle for religious tolerance and the creation of a secular state in Mexico.

The existing epistolary documents reveal the relationship of mutual support and support between her and her husband in dealing with family problems during the period of the Reformation and the military invasions of the country. Margarita did not fear political struggle if it was inspired by disinterest and honorability, and as proof of this, she was the first woman in the history of the country to appear as a collaborator of an elected president, with an attitude of her own.

When Juarez was governor of Oaxaca and General Antonio López de Santa Anna was emerging from a defeat against the United States, he banned Juarez from entering the capital of the state he governed, considering it a danger to peace, and when he returned to power, Santa Anna locked Juárez in the prisons of San Juan de Ulúa and sent him into exile in 1853. At that moment, Margarita's life changed.

Not only did the Juarez Maza suffer persecution by the dictator; they canceled the freedom of the press, banished all those suspected of conspiracy regardless of age, sex or illness, leaving whole families in the homeless.

Margarita, in addition to suffering separation from her husband, faced persecution and harassment from the conservative Santanist general José María Cobos who proposed to take her prisoner. With a large family to support and in difficult conditions, she managed to also provide resources to Juárez, until she returned to join the Ayutla Revolution. Pregnant with twins and six children, she escaped and managed to support her family, and financially supported her husband, who was in New Orleans and survived by rolling tobacco. At first, he received shelter and support in different farms, related to the Juarista struggle. Later, he opened a store in Oaxaca, in the town of Etla.

Just like this time, Margarita was with Juárez during the Ayutla Revolution, the Second French Intervention and the Second Empire of Mexico, where she showed loyalty and unconditional support to her husband, sometimes fleeing, such as during the Second Empire, to the United States, and returning to Mexico once the Republic was restored.

Margarita died on January 2, 1871, when she was only 45 years old. Throughout her life, she was a representative of Mexican liberals, coordinated civil society efforts to contribute resources to the fight against foreign intervention, and was a worthy diplomatic representative of the Republican Government in the United States.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies