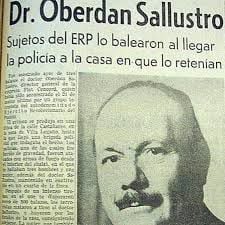

On April 10, 1972, the director of Argentina's FIAT Group, Oberdán Sallustro, was found dead in a house in Villa Lugano. His body had three shots, one in the head and two in the chest. The outcome came when four policemen raking the neighborhood knocked on the door of Castañares 5413's home and were shot away. For twenty minutes the block was paralyzed by the shooting. Until from the house they yelled to the cops that they had Sallustro and that, if they didn't leave, they would kill him. There was a truce in fact, a moment of silence that was broken by the sound of three shots, and immediately, three men escaped through the back of the house.

When the police broke in, they found a young woman, who was alone and still in the living room, unarmed.

Sallustro was the son of Italian parents. He was born in Paraguay, but lived in Turin since he was a child. He was part of the anti-fascist resistance that fought Benito Mussolini, and after the war he received his doctorate in Jurisprudence and began his career as a manager in the FIAT Group. In the 1960s, when the company had moments of conflict with workers, it was sent to Argentina to boost the production of automobiles.

The decision to kidnap came at a time when, due to arrests, falls and party crisis, the guerrilla organization PRT-ERP (Revolutionary Workers Party-People's Revolutionary Army) operated with a de facto autonomy, with “parallel leaders” that decided its military actions outside the agencies of the party. In the last quarter of 1971, the Buenos Aires Military Committee was in charge of Osvaldo Sigfrido De Benedetti, “El Tordo”.

De Benedetti put two operational plans into operation. One of them was in the air, but they were not being executed: the robbery at the headquarters of the National Development Bank, located a few meters from the Casa Rosada, where they took $10 million loot at the end of 1972, and the kidnapping of Sallustro, in the month of March. The operation was conducted by himself.

At the time of his abduction, the FIAT official was living in a house on Casares Street, in Martínez, north of Greater Buenos Aires. Every morning, his chauffeur and bodyguard José Fuentes drove him to the company's offices in downtown porteño. That was the first report that reported intelligence on Sallustro. From then on, the design of the operation was carried out. The information that the official would be traveling to Italy imminently accelerated times. De Benedetti decided to implement the plan, even though the “village jail” that would house him had not been completed.

In the original design, a car parked above Casares would alert by walkie-talkie when Sallustro left his house, and a van would shut him off when he crossed the corner of Pasteur. The van was ready. It had been stolen and adapted a few days before. And the car that would give the warning, too.

On March 21, 1972, the van locked up Sallustro's Fiat 1500, who was beaten out by a group of men. His driver, José Fuentes, was neutralized with a shoulder shot. The family warned that same day that the employer had a heart condition that required permanent attention. He asked the kidnappers to supply him with the drugs they were dealing with.

In the afternoon, in the bathroom of a porteño bar, a PRT-ERP statement was found that Sallustro was at the disposal of “popular justice” to respond on “monopolistic practices”, dismissals of FIAT workers and imprisonment of workers and union leaders.

For the reference in the statement, six hundred men from the Army, the Gendarmerie and the local police raked the province of Cordoba, where the automobile complex was located. There were twenty-five detainees.

A day later, from Italy, the president of the FIAT Group, Aurelio Peccei, landed in Buenos Aires to intervene in the negotiations. The arrival of Peccei marked the real dimension of the manager they had abducted to the PRT-ERP. The company considered Sallustro irreplaceable. But Peccei's interest in preserving his life was personal: he was his friend since the time of resistance to fascism — when Peccei was about to be shot — and they had worked together in Argentina. Peccei — and also FIAT — was ready to give everything for Sallustro's freedom.

The demands of the PRT-ERP for their rescue became known two days after the kidnapping. They had to do it in forty-eight hours, under penalty of firing. Five of the seven points were not difficult for the company to resolve, but they were within reach. But two of them could only be resolved by the military dictatorship, then led by General Alejandro Agustín Lanusse: the freedom of workers and trade union leaders arrested by the conflict with FIAT and the release of fifty prisoners from the PRT-ERP.

The guerrilla organization proposed moving them to Algeria or another country to be agreed.

Peccei's presence in Argentina put additional pressure on Lanusse. The president of FIAT wanted the dictatorship to exhaust all instances for his friend to appear safe and sound, and that demand was also expressed by the President of Italy, Giovanni Leone, and Pope Paul VI in their sermon on Sunday in St. Peter's Square.

Lanusse blocked the pressure with a statement he released after his meeting with Peccei. The dictatorship would engage in deals with the PRT-ERP. They would not do it or allow FIAT, or any third party to do it.

In short: for the dictatorship, the Sallustro case was an internal matter, within the exclusive competence of the Argentine State and would act as such, in accordance with its own convictions.

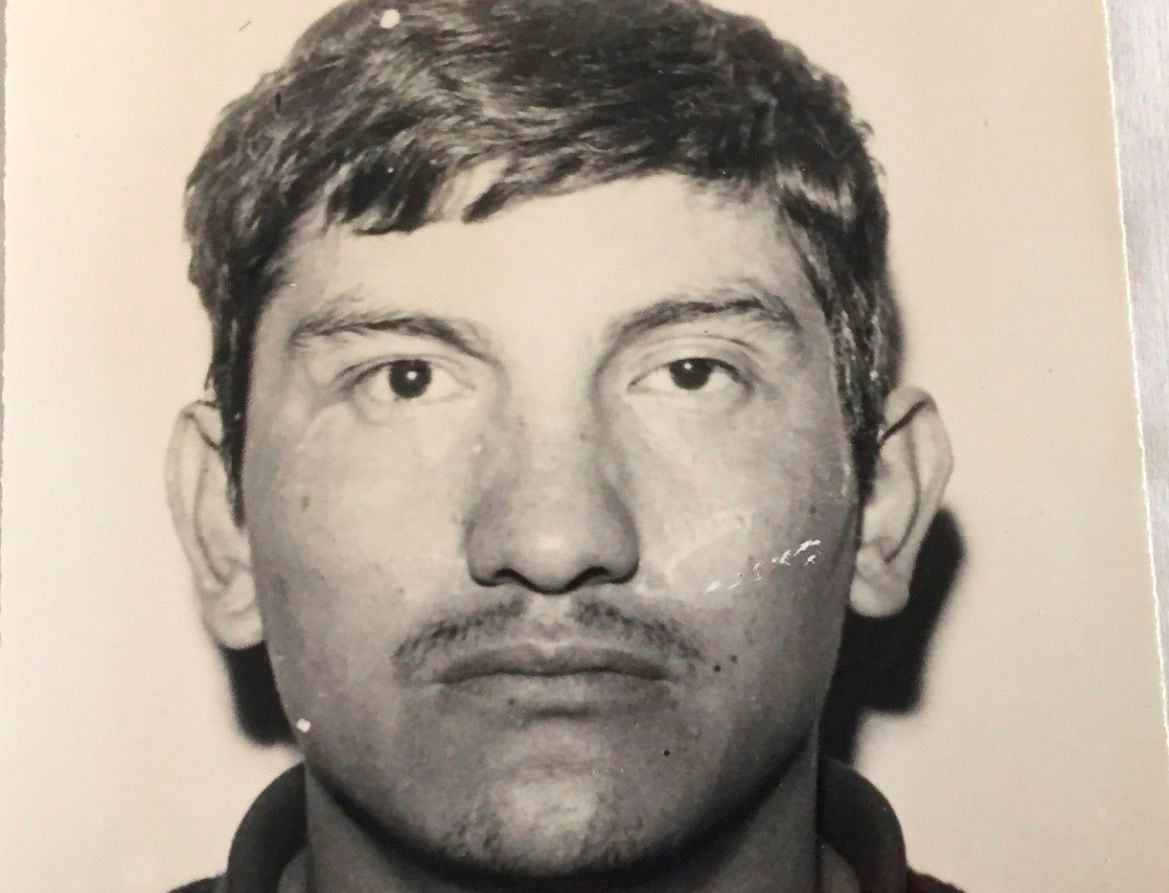

After his abduction, Sallustro had been transferred to Reconquista 180, a house in Villa Ballester. They placed it in the lounge chair of a basement located under a piece. There they took a photo of him, which they distributed as proof of life, in front of a sheet with the inscription “ERP. To win or die.”

Sallustro was wearing a white shirt and a serene and uncertain expression.

The house was not prepared as a “people's jail”. A few months ago it had been rented by two PRT-ERP militants who signed the contract with legal names. They were about 25 years old. The young man would come and go, almost always at the same times, with a white Citroen van. The woman, only a few months pregnant, swept the sidewalk and made purchases in the store at different times.

Sallustro spent nine days in the basement of the house. The treatment was kind. He told his captors anecdotes about the antifascist resistance in the Giustizia and Libertabrigades. At one point he wanted to write a note for his family and they gave him a paper and told him they would send it to him. It was a short letter, written in Italian with the pen that he had kept at the time of the kidnapping, and it came into the hands of his family that same night. It was addressed to “Ida and children, grandchildren, brothers and friends of FIAT and the entire organization”. It said:

“I'm fine. I remember them all. They treat me with deference. I embrace everyone and bless all children present and distant. To all of you a very strong embrace reminding you, for your serenity, that I have always acted in order with my conscience. Affectionately, Oberdán Sallustro.”

Calligraphic expertise certified that the letter corresponded to the director, and its ink allowed to confirm that it had been written a few hours ago. On the basis of that conclusion, the track was abandoned in Córdoba and the search focused on the Federal Capital and Greater Buenos Aires. About four thousand men from the Army and security forces inspected homes, depots, factories, railway playgrounds. Control checkpoints were installed on roads, avenues and streets. The finest and most methodical search advanced on the rental contracts of houses signed in the last three months by young couples and with purchased guarantees.

Meanwhile, Peccei — who had not taken anything from his meeting with Lanusse at the Government House — decided to act on his own account and engage in direct dialogue with Mario Roberto Santucho, head of the PRT-ERP, then detained in Devoto prison.

It was a solo meeting in the last days of March 1972. Peccei explained to the guerrilla leader the difficulties he faced in achieving the freedoms he demanded prisoners, workers, trade unionists and guerrillas and lawyer Alfredo Curuchet, who was arrested without judicial process. That obstacle was insurmountable. Lanusse was not permeable to negotiation.

FIAT could only significantly increase the ransom figure, but it was not in a position to release the prisoners. Santucho left the door open for a future negotiation with Peccei and sent a message to find out what Sallustro's safety was like. De Benedetti replied that it was guaranteed.

Lanusse would close the door of the dialogue: he ordered the transfer of Santucho, Curutchet and some twenty guerrillas from Devoto prison to Rawson prison. Peccei left unexpectedly for Italy. He left a message for the PRT-ERP. “I was also a guerrilla fighter in Italy, but I was always willing to respect human life.”

In those hours, the investigation approached Sallustro. One raid led to another. In less than two days, the police arrested twenty-eight people.

One of them was Carlos Ponce de León. In an interview with the author of this article, almost fifty years after the fact, he recounted:

I was a fighter. He worked in a rubber mixing and steel rolling mill, Castells Hermanos, in Bajo Flores. I rented in Ramos Mejía, on Bolivávar street. He was a turner. I joined the match in '68. I was in the Buenos Aires Regional and they sent me to a cell with a seminarian, (José Luis) Da Silva Parreira, since '68 I was operating with him. He was a school teacher. In the cell was his wife Mirta Adriana Mitidiero, who was an English teacher for Ford executives; there was Da Silva Parreira's sister, Elena María, and her husband, El Gordo (Angel) Averame, who was very poor, the mother washed the clothes of the convent and the father picked up the garbage from the street, was municipal. El Gordo worked at the Derga shoe factory.

I had met Sallustro. I worked at FIAT de Palomar. The chief of staff, who had been Sallustro's private secretary, invited me to lunch at noon at the factory, and the second time, when I went to the proficiency test, Sallustro was just visiting. That was one of the advantages I had over the rest of the command. I knew his face, his height. To make the bag where it was bagged, you had to know the height. He was tall like me, one meter eighty-five. That was in '67.

When I entered the cell, the operation was planned by the Military Committee. My job was to get him out of the car. The objective was to kidnap him for 48 hours and ask for five points: one million dollars for the TRP, one million dollars for distribution, reinstatement of FIAT workers, the release of the detainees of Sitrac-Sitram (from the class trade union current) and the departure of the Gendarmerie from the factory (in Cordoba). There was no more.

I did most of the checkup with the partner Mirta Adriana Mitidiero, the wife of Da Silva Parreira. We went almost every morning. It was a relatively easy thing. He was dressed as a cane. Afterwards, all the witnesses said I was a cop. There were many security companies in the area. Gray hair everywhere, some in civilian clothes. Sallustro's house was in a quarter block. The car came out from inside the house, they didn't come looking for it. They came out in the range of ten and twelve at noon. To do the checkup I asked for the change at work, I started working in the afternoon. And then I went back to work in the morning, six to three. The check-up lasted fifteen days. The operation rushed because someone lowered the fact that he had a meeting in Italy. Sallustro was the third in the world FIAT. Agnelli, Peccei and Sallustro were coming. And we didn't know if he was coming back or not.

The design was made, a Dodge truck, in which all those who participated in the operation were going to be, was going to close the way. There was one who parked it, and it was going to do something and it didn't come back, and one of those who was behind in the checkout was passing by. And there was also a Fiat 1500, I think with just one, dressed in a driver's hat, as if waiting for someone, on the sidewalk in front of the house. The Fiat 1500 had to warn that Sallustro was leaving and close it from behind so that it would not fall back. The only question we had was whether the driver was a bodyguard. We didn't rehearse the operation. When Sallustro's car passed, the van closed his way, the car stopped. There was no crash. We all went down. La Petisa and Vasco went on one side of the car, and El Gordo and I went the other. There were people, neighbors watering.

I went to the open face and in a suit. He never operated like a beggar. He always operated in a suit. I was mistaken for a reed, tall, darocho. I caught Sallustro's neck; he was on the driver's side. The bodyguard is seen to have patted the glove compartment and they put the chumbazo in it. And I take Sallustro out of the car, put a stump on him because he didn't want to get out, he threw himself back, he was knocked out, we immediately picked him up, threw him into the van, put him in the bag, closed the bag and bye. It was a bag made of imitation leather. With a scissors that we had carried, I cut off the top area so that he could breathe.

I told him we were from the People's Revolutionary Army, not to shout because we had orders to kill him. And he stayed calm. We took him around Pasteur, crossed the tracks to under a bridge, and there, another mistake, the ping-pong ball (to start the fire) didn't fit into the mouth of the truck's tank. I had carried two cans of gasoline. We made the transfer, they put Sallustro in a Citroneta, fully conditioned so that there was no noise, and Da Silva Parreira and her partner took him to the house on Reconquista Street.

In the original plan we were going to have Sallustro between 24 and 48 hours, and we had it almost ten days. Why? Because what the military committee had said that there was a “people's prison” was a lie. And the draining of weapons also failed. I took the .45 to my house.

On the first day after the kidnapping, when I went to work, Antonio, who always opened the door, said to me: “Where is Sallustro?” “Oh, yes, I have it in my house...”. I don't know if he had marked me or told me because he was missing, but Sallustro was a terrible mess in the media. When I found out that Sallustro was not shot at 48 hours, I raise it at the first cell meeting: “If we said that the deadline was 48 hours, it must be met. If you got it wrong, you're screwed, but you have to stick to it. If not, it is a lack of seriousness.” And what I call “petty bourgeois impressionism” happens. The management didn't know who Sallustro was. When they saw the huge impact it had, they added the fifty prisoners of the party to exchange them for Sallustro. They were impressed by the guy. The fifty prisoners were to be exchanged for the kidnapping of General Sánchez (in Rosario). The plan for Sallustro was that of those five points, and for Sanchez, fifty free companions.

The following Saturday — on Saturdays I worked until noon — I went to Caseros Station, and there they gave me another appointment at Malaver or Chilavert station, I don't know, one of the two. And Da Silva Parreira picked me up with the white Citronette, I didn't look at anything, and we went into the house. I was already poisoned because we still had Sallustro. Parreira was waiting for the order to move him. The kidnapping was on a Tuesday, and this was a Saturday. And Parreira began to speak well to me about Sallustro, who was macanudo, with a barbarian preparation, and that poisoned me even more. In the house was the wife, who was pregnant. Sallustro was our job, we all guarded it. During the week, Fat Averame took care of him, I imagine. I had to watch over the weekend, which were the days I could.

When they considered it coming down, I went down. I put on my hood and talked to him like a worker. I kept a newspaper La Razón the day before the kidnapping, which said that an unemployed FIAT worker, who had been fired, committed suicide when it became known that his daughter had prostituted herself to support the family. I took out the diary and said, “Explain this to me.” To his comrades, he could justify the barbarities he did. Most were students and were fascinated. Not me. “I know people of your kind, I know them. If you can allow the workers to starve, I can believe anything about you. Don't give me the partisan thing (clandestine civil resistance), because I also know him. It may have been true. But FIAT was one of the biggest arms factories in the world, it's not an SME, so don't screw with me. I understand that you can turn your fellow students around because they have no hate. I do have hatred. That's why I want you to explain this to me — and I give the diary to Sallustro —, to explain to me why the workers were fired, why the Gendarmerie is inside. Give me an explanation.” The guy, quiet.

And then we played chinchón, I asked him what music he liked. And he liked (Jorge) Cafrune, he asked for the Zamba for Don Rosendo. I went, I got him the Winco, I brought him the record. The guy was very whole while I was there. Parreira's sister, who was a nurse, put patches on her kidneys and changed them. That Saturday, Sallustro asked me if I could write a letter to the family, I said yes, as a rule he left, and took out the pen, looked at it, slapped it and went upstairs: “How the hell do they let him write with ink. Give me a pencil...?” , and I brought him the pencil. The comrades had let him write the first two messages and were checking Buenos Aires for that. The ink let them know we were in the area. And the basement couldn't resist any raking. It was very visible. In one room after the kitchen, there was the basement.

The Federal Police have a very good laboratory, these are things that should not be underestimated. The problem was the ink. Sallustro had an ink very similar to the Rotring system. They were the first of their kind. I didn't know about the messages until then, but it had struck me that the first few days no one had stopped me and then I was stopped three times, once by the police and twice by the army, always when I crossed the Liniers bridge to take the bus in the province. They checked my sailor's purse, where I carried the plate, knife and fork. They asked me where he worked, “José Marti 1853″, what he was doing, “turner”, where he lived, “Ramos Mejía”. When I took him out of Sallustro's car, I took the jacket out of him, and El Gordo tossed him into the van, and he was left in a short-sleeved shirt. And he got the pen back when they handed him the bag. It's the problem of not having training. You can't leave anything to chance.

On Sunday I left and told Parreira that, if Sallustro was transferred, he would burn everything, the mattress, the Winco, and to warn that I needed to drain, get the .45 out of my house. The following Thursday — I learned this later — they gave him the order to deliver the van with Sallustro to that place. And on Friday or Saturday... I know it was March 31, they gave me the appointment, I grabbed the gun, went to the Caseros station and we went to a working house in Villa Bosch. There was Fat Averame with his wife. I started to disarm the gun, and they took advantage of the fact that the door of the hall had been left open and four types of Federal Coordination entered. I covered the gun with a diary, but the magazine of the .45 was left uncovered. For me, they came by chance. I had told Fat Averame: “Go shopping, talk to the grocer, make yourselves known”, because you were like “Martians”. They suspected. But I don't know if the house was sung, because if it was so they would have bulleted us. And the gray hairs did a legal procedure, called witnesses.

They took all three of us to Coordination (on Moreno Street, Federal Capital). They took me to the second floor, to torture. Seven hours will have been. I said who I was, where I worked and lived. I had my “minute” armed. (The “minute” is the data, of legal and verifiable appearance, that a guerrilla fighter had to give when he was arrested by security forces).

My house was clean, I didn't live in a working house. There was my wife, the dog and a parrot, they were all I had. A supposed doctor came, asked me what happened to me, I didn't answer him, and there came a guy who said he was a commissioner; he told me, you are so and so,” said my pseudonym, “and you took Sallustro out of the car. I knew everything. Then I knew where they knew it from. That's where the house on Reconquista Street jumped. Citroneta fell with my fingerprints, the Winco with my fingerprints... not just mine. The bed where Sallustro had been, they found their hairs. All the things I had asked to be burned. The planning of the operation, was on brown paper, that big. Everything in the house. This is how the fall occurred. Thirty-two companions fell, twelve operational houses, part of the sanitary posts, ten clandestine companions in Parque Lezama, who had taken them out of Rosario for the operation of General Sánchez that was about to be done. Then Judge [Jaime] Smart came to the Federal Coordination to question me, and I continued to deny everything.

(This was the testimony to the author of this article by Carlos Ponce de León, who was detained for the kidnapping of Sallustro from March 31, 1972 to May 25, 1973).

On Sunday, April 2, La Opinión titled: “The security forces would have an important lead in the Sallustro case.” A day later, on Monday, April 3, the Federal Police claimed that there were twenty-eight detainees related to the kidnapping and the PRT-ERP. A few hours before the Army broke into Reconquista 180 and arrested Mirta Mitidiero de Da Silva Parreira and her husband, José Luis Da Silva Parreira, Sallustro had been transferred to the Citroneta, still aimlessly.

They moved for several hours in search of shelter.

The determination of the head of the ERP, Santucho, to stretch the terms of an impossible negotiation — the Army would not release prisoners under any circumstances — contradicted the fragility of the infrastructure of their captivity. That fragility was evident when the Citroneta that was carrying the FIAT executive punctured a rubber, and they circulated on the rim to a rubber band. Afterwards, Sallustro was housed a house in Villa del Parque, the original “jail of the people”, which was not yet finished. They placed him inside a tent and summoned a doctor from the organization to monitor his health.

When on April 9 the doctor fell in another massive raid, Sallustro was again transferred. The raid was uncertain. There was no reliable infrastructure. He ended up in the room of a house in Villa Lugano, in Castañares 5413, where a PRT-ERP architecture student, Mario Klachko, lived with his wife Guiomar Schmidt, Brazilian history professor and member of the Revolutionary Communist League. They had met on a holiday in Camboriú.

At that point, there was no negotiation or clear direction. If the PRT-ERP killed him, it could set a precedent for future kidnappings, but he would get nothing, neither reinstatement of workers nor money nor a delivery of arms in Uruguay, as FIAT would have proposed.

Two weeks after his abduction, Sallustro had no way out: he was killed by the PRT-ERP or he would die when his refuge was discovered. Since then, the PRT-ERP did not disseminate any more communications, FIAT reduced its prominence in public statements and raking was also reduced.

The Sallustro case entered a week of paralysis, which broke on Sunday, April 9, when the police raided the house of Martiniano Leguizamón 4441, in the neighborhood of Mataderos. There he arrested the head of the operation, Osvaldo De Benedetti, along with nine collaborators.

It could be assumed that the fall of that house led to that of Sallustro, the following noon. If there was prior knowledge of their whereabouts, it was strange that only two men in civilian clothes — as the neighbors later reported — came down from a patrol car to identify the house of Castañares 5413, in Villa Lugano, and even more strange that, as soon as they were met with fire, a police operation was deployed throughout the area.

The shooting paralyzed the neighborhood.

Until from inside they warned that if they did not leave, they would kill Sallustro, and they killed him with three shots, and Klachko and two other guerrillas jumped through the bottom and escaped on the other side of the block, as if the police themselves had left the rear open, had laid a silver bridge to the enemy to escape from an area fenced.

When the police entered the house, Guiomar Schmidt was alone in the living room and surrendered without resistance. In the room was Sallusto, killed by three shots. That day, the FIAT official was no longer a problem for the military government. The case had been clarified, and there would be no more international pressure. In his clothes, Sallustro had a letter to Peccei in which he anticipated a farewell. He said: “At the expense of your conscience, know that I too am very serene because I will finally know the truth of Giorgio — a son of Sallustro who died in a tragic way — and of God.” And he greeted everyone, in particular Fuentes, his driver.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs