It's night and Pablo J. Boczkowski walks along Avenida Corrientes without a mask. The pandemic does not exist yet: it is another era, very distant, although very similar, to the one we are experiencing today. He walks on the gray path, just restored, and sees a family in a street situation. They are just numbers in the statistics of an increasingly unequal world. In the open weather, the family is piled up around a cell phone, a screen. “It struck me a lot. It was a scene of material scarcity and abundance of information,” says the Argentine researcher. He took some photos with his phone and kept walking, but that image lasted years in his head.

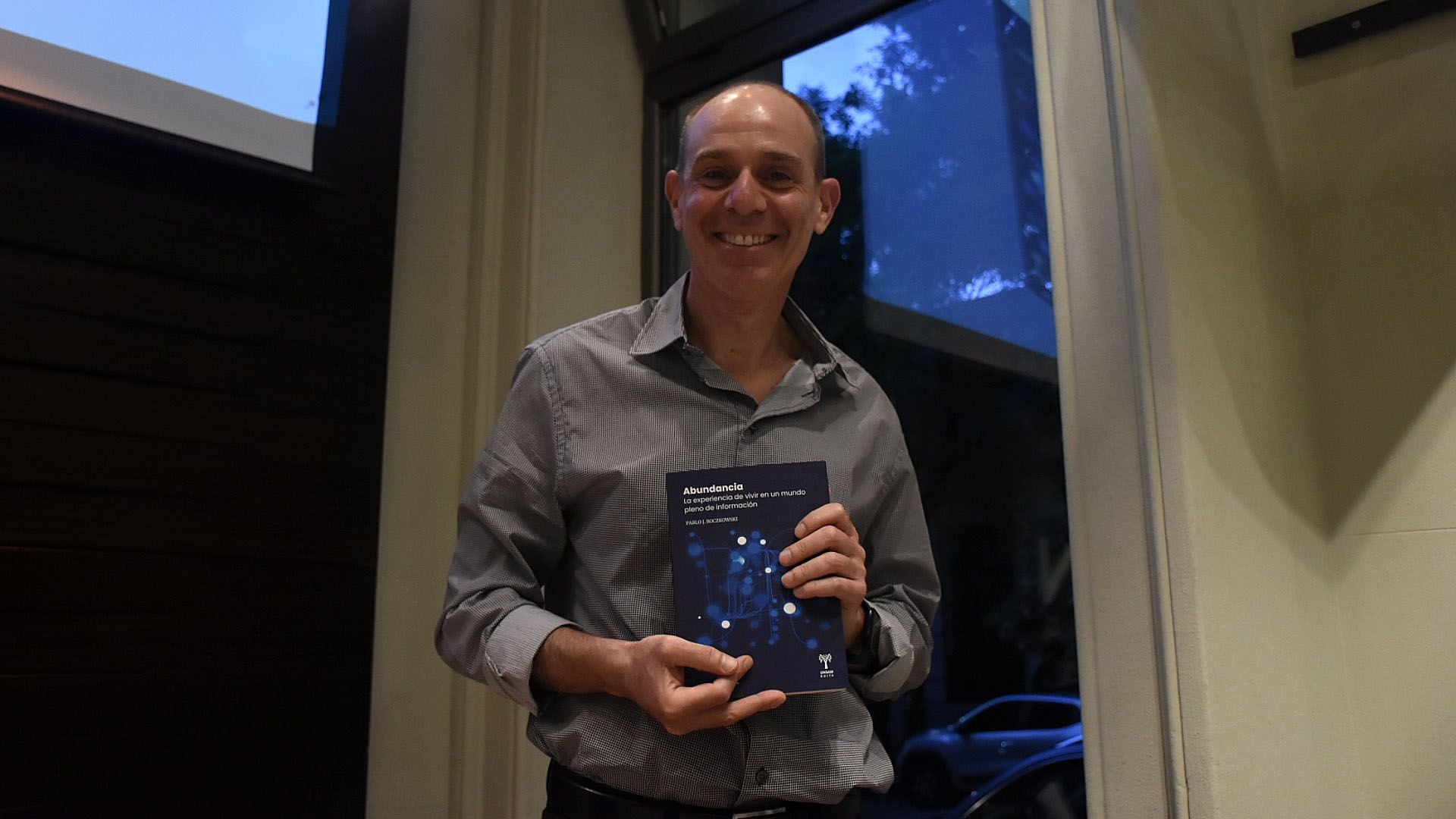

Thus, with this paradoxical street scene, Abundancia was born: the experience of living in a world full of information, a book that has just been published by Unsam Edita, the seal of the National University of San Martín, the second in the Futuro Amphibio collection. Now it's also night, but we're at Dain Usina Cultural, a bookstore on the corner of Thames and Nicaragua, Palermo Profundo. There are masks, many. It's the presentation of the book and about forty people listen to Boczkowski. “Since that night I felt taken over by the book, by the idea of that book. You don't really take books, books take you,” he confesses.

From then on, he began to investigate the consumption of information in Argentina. He talked to a lot of people, he listened to her. He was an interviewer, chronicler, even writer, then essayist and academic: he reversed the order. “It's a tango and calamaresque book. My intention was for the book to go against the grain; I don't know if I succeeded. In a world where academia prioritizes rationality, what I tried was to make people feel and make people think, not to divide emotion from thought. I launched myself against the bureaucratization of academia and research,” says the author this Monday afternoon surrounded by colleagues, family, friends, journalists.

He is accompanied by three people on the panel. One is the researcher Leila Mesyngier, director of the collection, the first to speak, the one she introduced to everyone, who highlights that Boczkowski “is an amphibious author” due to his ability to combine journalism and academia. The second is Silvina Heguy, director of strategy for DiarioAR and author of Viaje al fin del Amazonas. She argues that the book “addresses abundance from imperfection”, adhering to the statement that “information, platforms, technology are not good or bad; it is the audiences that give them meaning, audiences that are political and active subjects”.

The third and last, before it is the turn of the author of Abudancia, is Iván Schuliaquer, professor and Doctor of Information and Communication Sciences, who places this book in a trilogy marking how Boczkowski's interest as a researcher began in the media, continued with journalism and decided on the information. “Pablo is a provocateur, also a disturber, something unusual, because it also makes you want to discuss him”, adding that “what he does is a criticism of determinism. And if a book can be read in relation to who is fighting, here it discusses with the catastrophists.”

“In a world where everything seems to be known with a click,” says Schuliaquer — the era of algorithm, segmentation, consumer prototypes, where we are numbers justifying consumer trends —, “what Pablo does is ask people again.” Look for a thoughtful and heartfelt word that has nothing to do with the cold mechanism of completing a survey and discovering that “while a desktop computer connected to the internet can work in a way almost identical to that of a television, it is rarely experienced as a warm and comforting company like television.” Uses are often opposed to marketing.

He writes in the conclusions of Abundancia: “The wide variety of modes and purposes of use, linked in part to an even greater number of circumstances in which interviewees used their personal screens, rejects any possibility of establishing an overall optimal level of quantity and quality of information beyond which would have detrimental effects. Is it optimal to interact with and through a mobile phone during the entirety of a public transport trip — as Mariela does — or is it better to take a nap?” Sometimes technology offers a chance to “deal in other ways with the problems of silence and loneliness”.

Now, on this evening in the Dain bookstore, Boczkowski argues that while “it's hard just to be with yourself without being bombarded with information”, “without the abundance of information the health crisis would have been much more difficult than it was.” What is technology but a cold and strange tool that humanizes itself in the heat of the use we give it ourselves? In this pendulum is this researcher, a university professor at different faculties around the world, director of study centers and a world-influential thinker around these topics: “The materiality in which we live is not made of silicon, but of sand”.

To this manifest and conscious impossibility of knowing everything, Boczkowski adds estrangement, something typical of journalism, even more so of literature. That estrangement, he says, was a fundamental element in the writing of this book: “I wanted to keep the eyes of the child who lives amazed.” “The world we live in is science fiction,” he says afterwards, pointing to the small camera on a tripod that broadcasts the presentation live. No one looks at it for more than a second; it is another object of the current landscape. “That, when I started studying, belonged to science fiction,” he says.

“This book is a farewell to the media... well, to the media as we knew them.” The one speaking is Ivan Schuliaquer. “Pablo is very counterintuitive. It is when he says, for example, that we are less alone, that technology does not take you away from others, as many often repeat.” He also takes up a fundamental line from the book when he says: “Why would technologies be perfect if societies are not? Why would technologies make us perfect?” Boczkowski smiles and thanks. The presentation concludes with applause. The camera, now, stops transmitting.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs