(Infobae today begins publishing MEDIAMORPHOSIS, a series of monthly articles on the international journalistic media market, written by Juan Antonio Giner, with permission from La Vanguardia de Barcelona).

When the aristocratic and phlegmatic Denis Hamilton, director of the Sunday Times, presented the project to Lord Thompson in 1962, the newspaper's owner exclaimed in terror: “My God, this is going to be a disaster”. But, for once, that Canadian garrulo was wrong, and a few years later he recognized that that magazine had become a formidable “sales engine” for the Sunday edition of the London Times.

It is well known that Roy Thompson could only be convinced if whatever it was (new director, new supplement or new columnist) guaranteed that he would make more money with it.

Sir Denis Hamilton was winning it, the newspaper was a success and so he asked him to see that new magazine, in full color, as an investment in the future. I argue that, as usual, never convinced Lord Thompson's pesetero.

The beginnings were not bad but fatal: in the first 18 months of the new “colour magazine” the Times lost the astronomical figure of 900,000 pounds (more than 10 million euros today). Little joke. Hamilton recalls in his memoirs that they also received a thousand letters of protest from older readers who complained about the style and graphic content of the magazine inserted in a “sábana diary” still printed in black and white from the first to the last page.

The Sunday Times then sold a million copies and it was a money-making machine. That's why, and to Thompson's surprise, his two biggest competitors also launched the same type of full-color magazines: The Observer on Sundays and the Daily Telegraph on Fridays.

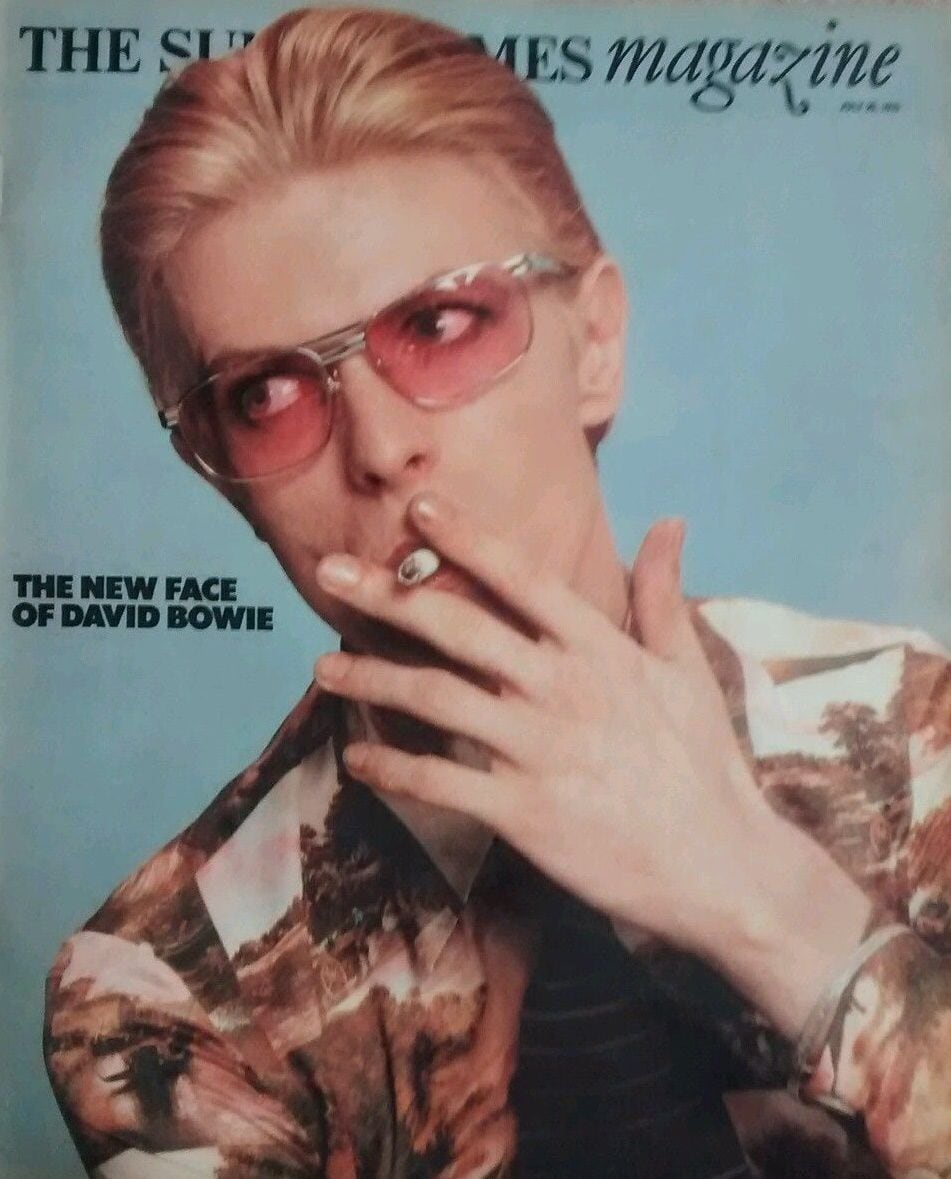

Sir Denis Hamilton thought, and was not mistaken, that Sunday Magazine would attract more young readers thanks to color and aggressive and shocking photographic content, even more so when the Illustrated London News was already in decline.

But not only did more readers arrive (sales increased by 25%), but commercial success was brilliant with advertising revenue unimaginable today: for many weeks each edition more than a million pounds was billed in a magazine of more than 120 pages.

Lord Thompson was exultant; he had discovered the great secret, then and now, of these “sunday magazines” as a luxury advertising claim for newspapers, as a decoy for younger readers and, above all, as a pretext for buying the Sunday newspaper.

This had happened at the turn of the century in The World, Pulitzer's newspaper in New York (World Pictures) or in the weekly supplements with gravure printed photographs of the New York Times (Mid-Week Pictorial Supplement) or La Vanguardia, whose print from Graphic Notes began to be published in 1929.

The Sunday Times journalists began to collaborate with the photographers of the Magnum agency and this resulted in a mix of reports on “pure and hard photography” (wars, crimes, hunger, disease, drugs and the underworld) and others typical of new countercultural lifestyles, always thinking about new and young people audiences.

The harshness of many of these photos frightened some advertisers who feared seeing their brands contaminated by those “blood, sweat and tears” coverage, but surveys soon showed them that the “sunday magazine” attracted many more readers than the black and white newspaper.

Over the years, different variables of this magazine achieved the same results: from the glamour of Le Figaro Magazine and the sophisticated M of Le Monde in Paris, to the E of Expresso in Lisbon, the New York Times Sunday Magazine or the How to Spend It of the Financial Times in London .

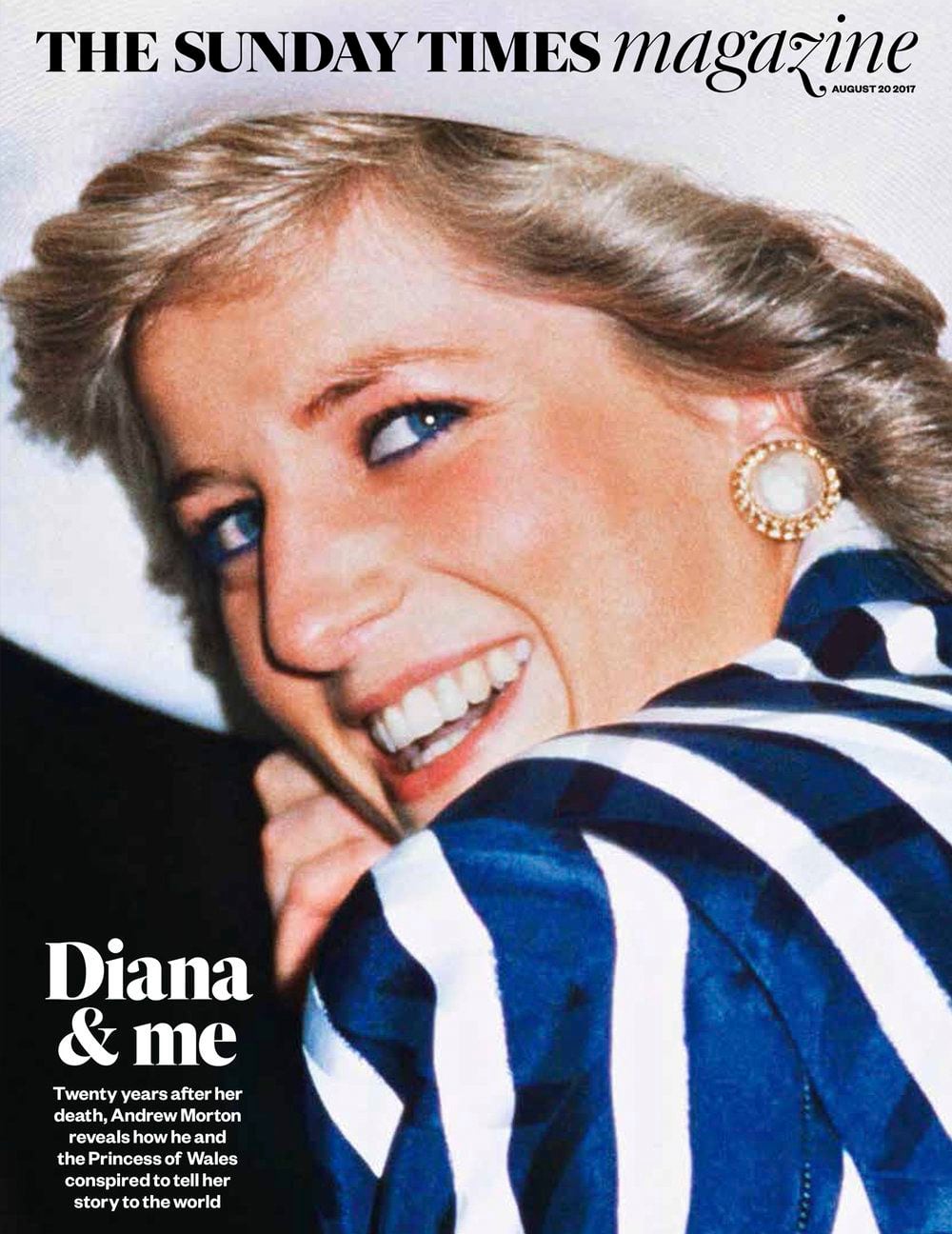

In all these and many other cases, the evolution was very similar: from being a means of capturing color ads, it went to publications that attracted young people who did not read newspapers and, finally, to the definitive argument: being the main reason why Sunday editions of newspapers are bought.

A few years ago, the weekly Expresso de Pinto Balsemao in Lisbon relaunched its magazine, which was designed by the Spaniard Antonio Martín and the Brazilian Marco Grieco: it increased its pagination and printed it in giant size. It was a success because its readers recognized that this mega-magazine was the “main reason” they bought the newspaper

La Vanguardia pioneered the use of photography and I remember Milton Glaser's admiration for the weekly supplement Gráficas Notes that printed in gravure was published in the 1930s. After its redesign in 1989, La Vanguardia promoted a Sunday magazine with Pepe Baeza and Carlos Pérez de Rozas as graphic editors. A tradition that continues today under the baton of Pedro Madueño and Rosa Mundet in new formats of journalism under the baton of the newspaper and outside the newspaper.

And the fact is that “telling stories” with photographs, the magical “Show don't tell” remains a journalistic genre as popular as it is unbeatable either on printed paper or in new digital formats: in London, New York, Paris, Lisbon or Barcelona.

* Juan Antonio Giner is a founding partner of the Innovation Media Consulting Group (London, UK) and author with Carlos Soria of “Stories of Innovation” (Amazon).

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies