On a set of canvases carefully placed side by side, the different shades of pink and brown form the flowers and trunks of cherry trees that frame the figure of what any lover of Japanese culture recognizes as the imposing Mount Fuji, an undisputed icon of that country: the 4-metre-long work by two tall, who for several months has been decorating one of the rooms of the Japanese Garden, belongs to the artist Julia Funai, a 78-year-old woman who considers this painting a “milestone” in the career that began just two decades ago, when she was able to free herself from the impositions that plagued her in the past and decided to rediscover herself, pursuing her dreams and embarking on a path that led her to exhibit in galleries internationally and to become a well-known figure within her community.

Today his home is full of paintings, dozens of them distributed in two rooms exclusively intended for the storage of creations that for different reasons were not put up for sale, and many others in the workshop where he teaches his students the technique that he perfected over time, also located within his large department of the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Flores.

However, this was not always the case: for much of her life Julia was a modest housewife who dedicated all her days to serving her husband, she had to keep strict schedules, prepare food for her family every morning, afternoon and night, always dress in dark clothes and remain quiet at social gatherings.

“All that had nothing to do with Japanese culture, machismo was everywhere and I am from a generation in which the mentality was still very closed. It took a lot for me to get out of there, even until recently I kept signing my paintings with my married name. He didn't encourage me to change it for fear of what he might do to me from wherever he is now,” the artist told Infobae.

Despite having been in that environment for many years, to the point that she got used to and accepted all those mandates that were imposed on her, when she was widowed by loneliness at 55 she pushed her to seek her own destiny and it was then that, little by little, she began to experiment, both with her hair, that she cut in different ways and dyed in different colors, such as with clothes, music and oriental painting, in which he discovered his true passion.

Julia was born in 1943 in the City of Buenos Aires. She is the daughter of a Japanese immigrant from Kumamoto prefecture who after World War I decided to settle in Argentina, where she met his wife, a Japanese descendant.

Like her, her father was also an artist, albeit from other branches, as he served as a dance instructor, writer and teacher of Ikebana, the discipline dedicated to flower arrangements.

“He was a reserved man with few words, so he complemented himself very well with my mother, a lady with a stronger character, who was in charge of the house. She worked a lot of things, she did everything. I'm sure it would have been brilliant if I could have studied, but I had to feed us,” he recalled.

In the closed circle of the Japanese community in Buenos Aires, Julia grew up among the dances and kimonos she wore at events to which her father was invited, where she felt “contained” and far from the discrimination she suffered in primary school because of her roots.

At the age of 15 she met and became a girlfriend with who would later become her husband, a person much older than her, elegant and also descendant of Orientals, whom she dedicated herself to pleasing until she died in 1998, when her life took a turn.

Secluded in her home and with a good financial background, the woman felt that she was not complete and the multiple visits to the tarotistas she found in the Buenos Aires suburbs did not give her the answer she needed, until one day they read her birth chart, which indicated that her destiny lay in art and teaching.

The start of his career, the trips to Japan and the creation of his own style

This is how Julia decided to call an old friend who sold Bach flowers, who in turn contacted her with a teacher of Japanese painting and thus began to take her first steps into the world of oil drawings.

Little by little she became a much freer person than she was before, and although she was already old, she was encouraged to break away from all the structures that bound her during her marriage and enter an environment that until then was completely unknown to her.

The first instruction he received was a screenshot of the two main styles that have dominated the culture of that country for centuries in terms of paintings: Sumi-e, which is characterized by its black and white strokes made with Chinese ink on sticks, by the simplicity of its figures and by its large voids, and the Nihon-ga , much more colorful than the previous one and a little more modern.

From the beginning he was inclined to the second, for his “love of working with colors, mixing them and playing”, and he quickly improved his technique. Soon he was exhibiting in the main museums of Buenos Aires and then also in New York and Canada, but he got tired of the commercial circuit and in 2013 he participated for the last time in an exhibition in which he had to negotiate a space in exchange for a small part of the profit. It was at the San Miguel Palace.

Again disoriented, in 2017 she decided to spend her last savings on traveling and getting to know Tokyo better, where she had already been in the 90s as a tourist, but this time she devoted herself to visiting art galleries and connecting with the local scene.

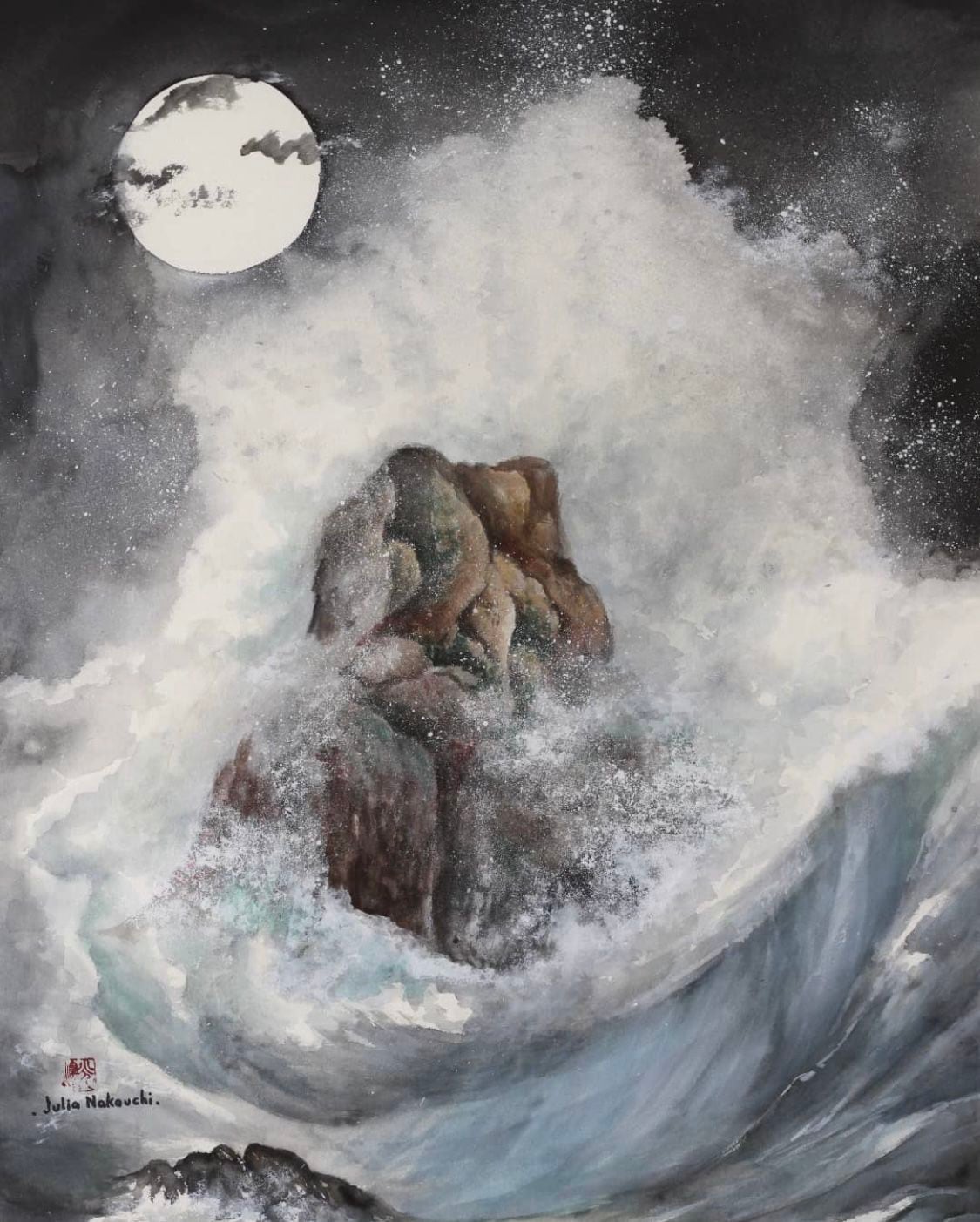

By that time she had already been appointed a Member of Notables of the Japanese Garden, but in the diploma they gave her a detail appeared: “They told me that my works could not be classified as Nihon-ga and that they had to put me in the category of painter. It was the best thing they could have said to me, because that was my thing, painting,” Julia recalled.

What happened was that the already professional watercolorist had decided to modify the rules of this traditional style, combining it with some aspects of Sumi-e and also incorporating some materials that had never been used for this type of work, such as plaster.

Two years later she called her niece who is living in Japan and asked her if she knew any watercolorist from that country who could teach her so she could continue learning, and after an exhaustive search the young woman found Sato Kozo, who worked in various shrines and agreed to receive her.

Already in the land of her ancestors, on a train trip to Kyoto, the artist first saw Mount Fuji, a volcanic cone that lies between Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures, which at 3776 meters is the highest peak on the island. This imposing figure was forever engraved on his retina and is part of many of his paintings.

“He is an icon of Japanese culture and represents me. It is serene and majestic on the outside, but one knows that inside, at any moment, it can exploit its full potential. That's why my logo is Mount Fuji,” he said.

When he was taking the seminar with Kozo, one day the woman asked him why he didn't correct her during classes: “If you allow me, I'll give you some advice, you have nothing to learn. You have something inside and I'm not going to impose my technique on you. His thing is not Nihon-ga, nor is Sumi-e, it is his thing, it is Ryu (Japanese word meaning style). You go ahead with everything, because you have your head in this century, not in the sixth century,” was the teacher's reply.

When she finished the course, the time she had left before she had to return to Argentina, Julia spent getting to know with her friends Kumamoto, the place where her father came from. Fate wanted an old childhood acquaintance to contact her on Facebook just then to guide her.

“It turned out that she was a civil servant in the area of culture of the government. He took us to the most important meditation garden in the city, to which no one has access, and there, in that Buddhist temple, I met my dad again. That's when I felt like I was a Funai. From there everything changed for me, because until that moment things were going well, people praised me, but at that moment I turned my profession upside down,” he explained.

Back in Buenos Aires, a new challenge was encouraged. Rodrigo, a musician from Buenos Aires he met when he wanted to take singing lessons and who became his close friend and collaborator, suggested that he make a mural on one of the walls of his room, a technique he had observed in Brazil and that fascinated him.

At first the woman accepted, although somewhat doubtful because of the physical effort required to paint large areas. He had a lot of experience, but he was 76 years old. Halfway through the job he realized that he couldn't hold his arm up for so long and gave up, but his assistant looked for a solution.

“He said 'if you can't paint on the wall, then do it on paper'. I didn't understand anything. He grabbed a canvas and explained to me 'we do it in parts and then with my dad we join them all together and put it in the courtyard'. I loved the idea,” Funai explained.

But when the painting was finished, it turned out so well that they decided to call the plastic artist Jorge Palacios, who was in charge of making the ensemble so that the joints between the different sectors of the drawing were not noticeable and ended up being exhibited in the Japanese Garden.

Then came the coronavirus pandemic and the renowned cultural space remained closed for more than a year, so the huge image of the night forest that the watercolorist made remained there for several months.

However, when the park reopened this first mural, it was claimed by the person who originally was going to own it and ended up in Rodrigo's house, but the authorities of the site had liked it so much that they asked the artist to make another one, who remains decorating one of the rooms and, of course, it is a representation of Mount Fuji.

Currently, Julia Funai continues to provide workshops at the Japanese Garden and at her Flores house, at the same time she sells paintings on her own and recently ventured into a new project, an online school that consists of a distance seminar with one-hour tutorials in which she teaches the technique she created throughout her career.

“There are three words that define being Japanese. The first of them is wabi, which means sobriety: Japanese are sober, in their home, in their food, in their whole life, and that is what we try to show in painting. The second is mono no aware, which is the sensation produced by things, such as haiku, poems that are not armed, that are the product of what you see generates, and that is what I tell my students that we have to achieve. And the third, which for me is the most beautiful, is utsuroi, transience. For the Japanese, life is fleeting Good and bad is fleeting. That's why they don't talk about the beauty of a flower, but about a beautiful flower. I add that we, from painting, managed to eternalize that moment”, he closed.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs