(From Warsaw, special envoy) Natasha cries unintentionally. She seems angry with herself when she lets out a few tears of helplessness. His blue eyes soak and his eyebrows frown.

“The sound of bombs is a special sound, in the worst way,” he says. “Even if you haven't heard it before, you recognize it instantly.”

He comes from a city near Kiev and his trip lasted three days. With a friend and her son they traveled day and night without water or food and gasoline problems (“like everyone else”, interjects Katerina, a Ukrainian volunteer in Warszawa Centralna who offers herself as an interpreter for Infobae).

Warszawa Centralna, the most important railway and metro station in Warsaw, has become one of the most crowded Ukrainian refugee epicenters since the war broke out.

More than a tenth of all those fleeing Ukraine arrive in the Polish capital. Some settle there, while others continue to travel to other destinations, so the main train stations become crowded centers where people camp on the flats, fatigued and terrified. Locals try to accompany them as they can, with assistance, food and a support arm.

There are volunteers who speak English, Italian and Spanish, as well as Ukrainian and Russian. There are medicines, coffee, a place to eat a hot plate and people who help organize a trip to a third destination.

Natasha goes to Finland, where she does not know anyone, nor does she understand the language, but where she leaves because she heard that Ukrainian refugees are treated very well there. He left behind his parents and everything he knows. She is alone, and she cries, now with resignation. “The only thing I brought was my extreme love for my family and for my country. There's nothing more important than that.”

He didn't think the invasion would happen until the last second. “They bombed near where I lived, a few miles away. I woke up to the sound in the middle of the night shaking. At that moment I realized what was happening. I told my family, but they didn't believe me. Three days ago, at last, I decided to leave.”

Boris comes from Kharkiv, one of the most dangerous places now in Ukraine. According to local news agencies, around 600 homes, 50 schools and health care facilities were destroyed by Russian bombings in that area. Boris traveled with his wife and two children aged 12 and 14. While talking to Infobae, his wife is on the phone trying to work out the last details of his transport to Spain, where he will go to meet his brother.

They escaped nine days after the invasion. They took a long time, because they were stopping at night for the children. “We spent a week in a refugee basement. At first it wasn't so bad because we could come and go. The last few days we had to stay there, quiet and hidden. It was terrible for my children.”

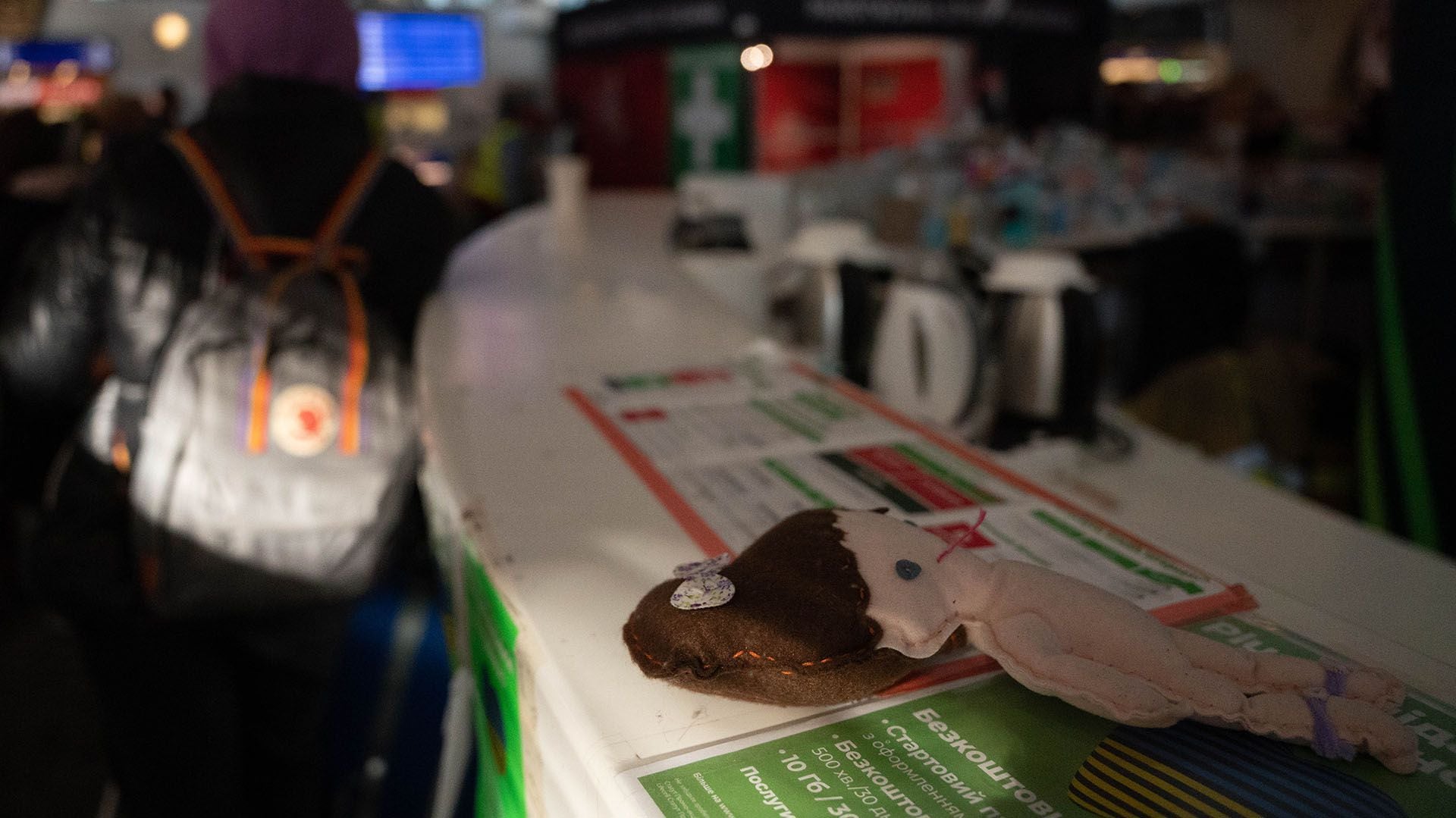

They arrived a week ago at the train station, spent a few days there, others in a hotel and the next day their bus will leave for Spain. “I brought only documents and things for the children, I regret not grabbing something else, but we couldn't, we had to leave.”

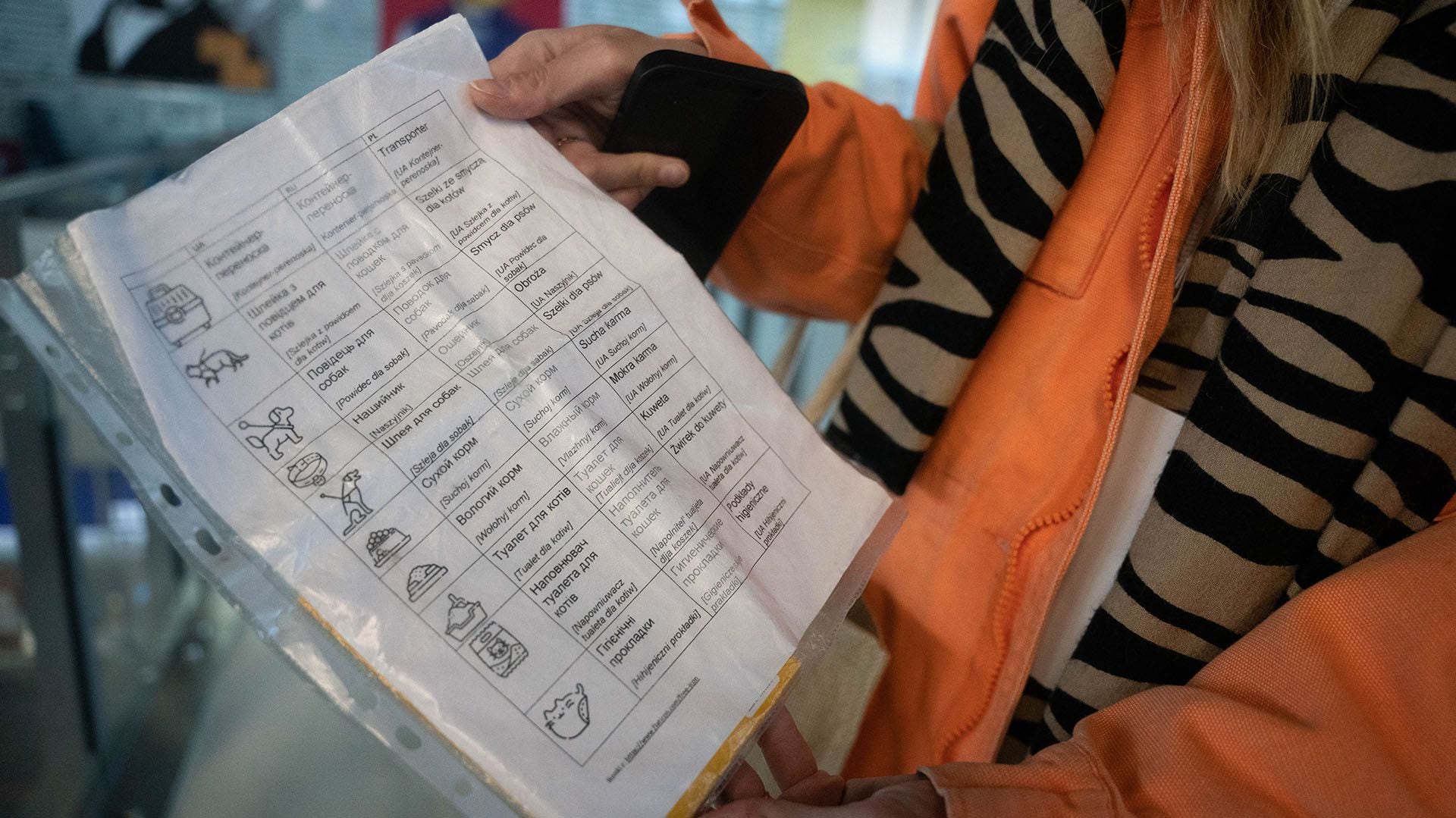

A tall volunteer, with red hair, walks among the people. He has a sign on his back indicating that he is in charge of pets. “We help animals traveling with Ukrainians. We saw many cats and dogs and some hamsters and guinea pigs from India. And some geckos! We give them food, water, vaccines, medicines and the necessary care until they have to leave.”

Gala escaped from Dnipropetrovsk, with her family of 13 people. Now they lie on the top floor of the station. Several makeshift mattresses line next to a row of baby strollers. Many sleep, others look suspiciously, but Gala wants to share her story, as she looks at her young grandchildren huddled around her. “We have been waiting at the station for two weeks. The problem is that we have Ukrainian passports and we can't leave Poland.”

He traveled wearing it, barely wearing a robe as a coat. He regrets that many of his people were left behind, but the three-day and three-night trip was necessary. “I want to go back, but when it's safe. Not now, even if it tears my heart.”

Fotos: Franco Fafasuli

Keep reading:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs