A very sharp sound in the forest caught the attention of Ecuadorian biologist Jorge Brito. He thought it was the cri-cri of a cricket, but he found a kind of toad with a prominent nose that since its discovery, a century ago, science believed to be dumb.

“At first I thought it was some cricket that was out there vocalizing, but I noticed it and I was attentive,” recalls Brito, from the National Institute of Biodiversity (Inabio). What he saw next was a toad that “although it did not inflate the uvular sac, there was a small flicker” on his chin. Already at the camp, this specimen of the species Rhinella festae made a sound again. It was not the common croak of toads, but a very fine “ruuur-ruuur”.

By chance, he found the evidence that brought down the idea that this species could not sing because of its particular vocal anatomy. In February, the journal Neotropical Biodiversity reported the finding. In their article, Brito and fellow Ecuadorian biologist Diego Batallas described the sound of this species that inhabits the Amazonian mountain ranges of Cutucú and the Condor. The latter extends from Ecuador to Peru.

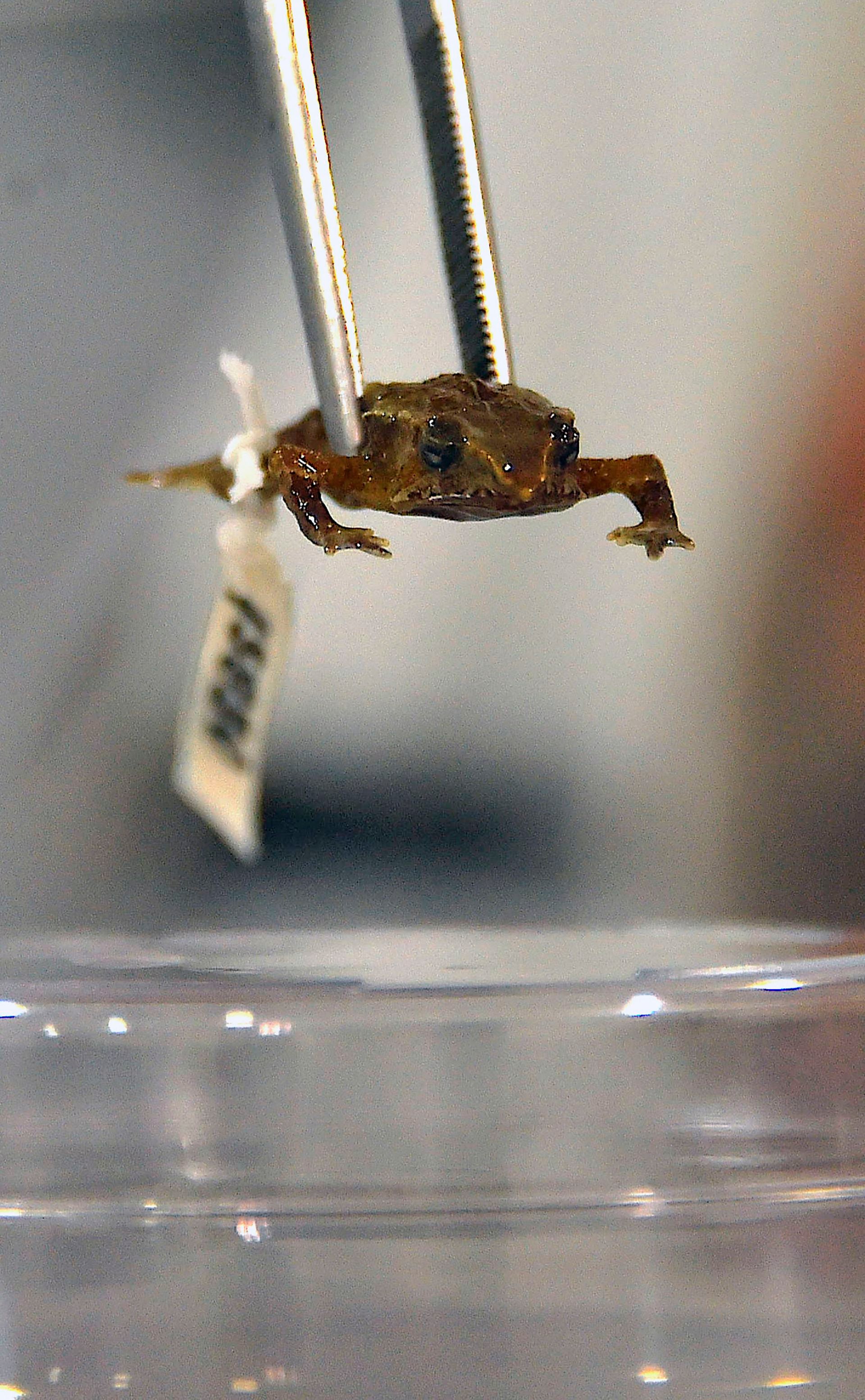

“This particular song by Rhinella festae is the first time it has been recorded and it is somewhat surprising because, in a few words, it should not sing”, he tells AFP Batallas. This variety is known as toad from the Santiago Valley. With brown and rough skin, it can measure between 45 and 68 millimeters and is characterized by the head ending in a nasal prominence.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) included it on its list of nearly threatened animals. The dominant frequency of his singing is in a range of 1.21 to 1.55 kilohertz, with one to two notes multipulsed, and an average duration of 0.72 seconds. “A very subtle sound and very difficult to hear in the field,” says Batallas, who before becoming a biologist was a chorus singer at a conservatory.

Rhinella festae toads lack sack and vocal clefts. The first is a cartilage that inflates and acts as a speaker; the second, a kind of valves that regulate the entry and exit of air. Located under the chin, the vocal sac allows amphibians to amplify their song to be heard more than 1 kilometer away.

The fine sound thread of the Rhinella festae would prove that all species of toads sing. “There are probably species that have gone unnoticed and that due to evolutionary processes that we don't know — which can be anti-predatory, that can be effects of the environment — do not need their sounds to be heard far away,” says Batallas.

In the case of the Rhinella festae, their singing is an announcement, as if it were a business card. In other species croaking is associated with courtship and the defense of territory.

Ecuador, a small but megadiverse country, has 658 species of amphibians registered. Of these, 623 correspond to toads and frogs and almost 60% are at risk or critically endangered of disappearing. Only Brazil and Colombia have more species of amphibians than Ecuador.

In a laboratory in Quito, Brito has the stuffed specimen of the Rhinella festae toad that surprised science. He still gets excited when he remembers the chance that led him to the discovery. In 2016, it compiled an inventory of the fauna that lives between the Upano and Abanico rivers, in the Amazonian province of Morona Santiago, on the border with Peru. One night, he says, he entered the forest and caught the sound that he first confused with that of a cricket. He contacted Batallas so that both, in the laboratory, will hear the call of the toad.

“The first time I heard I said: ugh! This doesn't sound like a toad, it's like some kind of a little bird, a trinito. It does not have the characteristic of an amphibian”, says Battles. Already with the certainty that it was a song never recorded by science, the researcher stresses the importance of finally having a sound identity like most species of toads. This finding allows the implementation of less invasive methods of research, since the entry of people to fragile habitats is limited to avoid the manipulation of specimens.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies