In an excerpt from chapter 5 of the book “La casa de la calle 30th. A story of Chicha Mariani”, journalist Laureano Barrera writes:

“I'm getting married.

He said it one night like the others, in May 1972, without preludes. Chicha and Pepe were silent. Daniel, who had just graduated, finished detailing the plan: he had accepted a job at the Federal Investment Council (IFC) offered by a former professor, and he was traveling in three weeks to a scholarship in Santiago, Chile for a regional planning course organized by the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC). Before leaving, he married Diana. The honeymoon would be in Salvador Allende's Socialist Republic of Chile.

“It was all so fast that I don't even remember if we toasted,” says Chicha when he recalls the journey that would be, perhaps, the beginning of the end.

At the fiancée's house, the news did not cause euphoria either.

Rather the opposite. Diana had to renounce the vows of the Baptist faith assumed at the age of 13 and rename herself in the Catholic flock.

Diana's father, Mario, had never been a practitioner, but he felt that abdication as a contempt for the values they had instilled in him. And she assumed it was the groom who was dragging her. That's why he didn't attend his daughter's Catholic baptism. A long time later, Bernardo and Daniel Teruggi, Diana's brothers, weave hypotheses about that wedding.

“No one at home understood the need to marry by church considering that neither of them had a religious history. I always thought it was more of a covering effect. To show themselves as a respectable marriage — Daniel Teruggi adventure from Paris. They went to talk to my father to explain. I don't remember if there was an argument, but the argument had been very confusing.

Bernardo Teruggi, the youngest of the four, talks about his sister one morning of suffocating heat. While preparing the mate, he listens to calls to finalize details of presentations: at the age of 55, he is director of the Academic Camerata del Teatro Argentino. He conducted more than twenty Rio de la Plata symphony orchestras. It took him a long time and many different therapies to grieve for Diana, he says. He stands and walks to the wall library. Take out the book “Peronism. Political philosophy of an Argentinian obstinacy”, by José Pablo Feinmann.

“I discovered several things about my sister in this book,” she says, while holding the volume in her hand. One of the things he says is that montonero paintings were verticalist. The montonero had to meet certain standards. Among them, being married by church. That's why she got married in the Valley church.

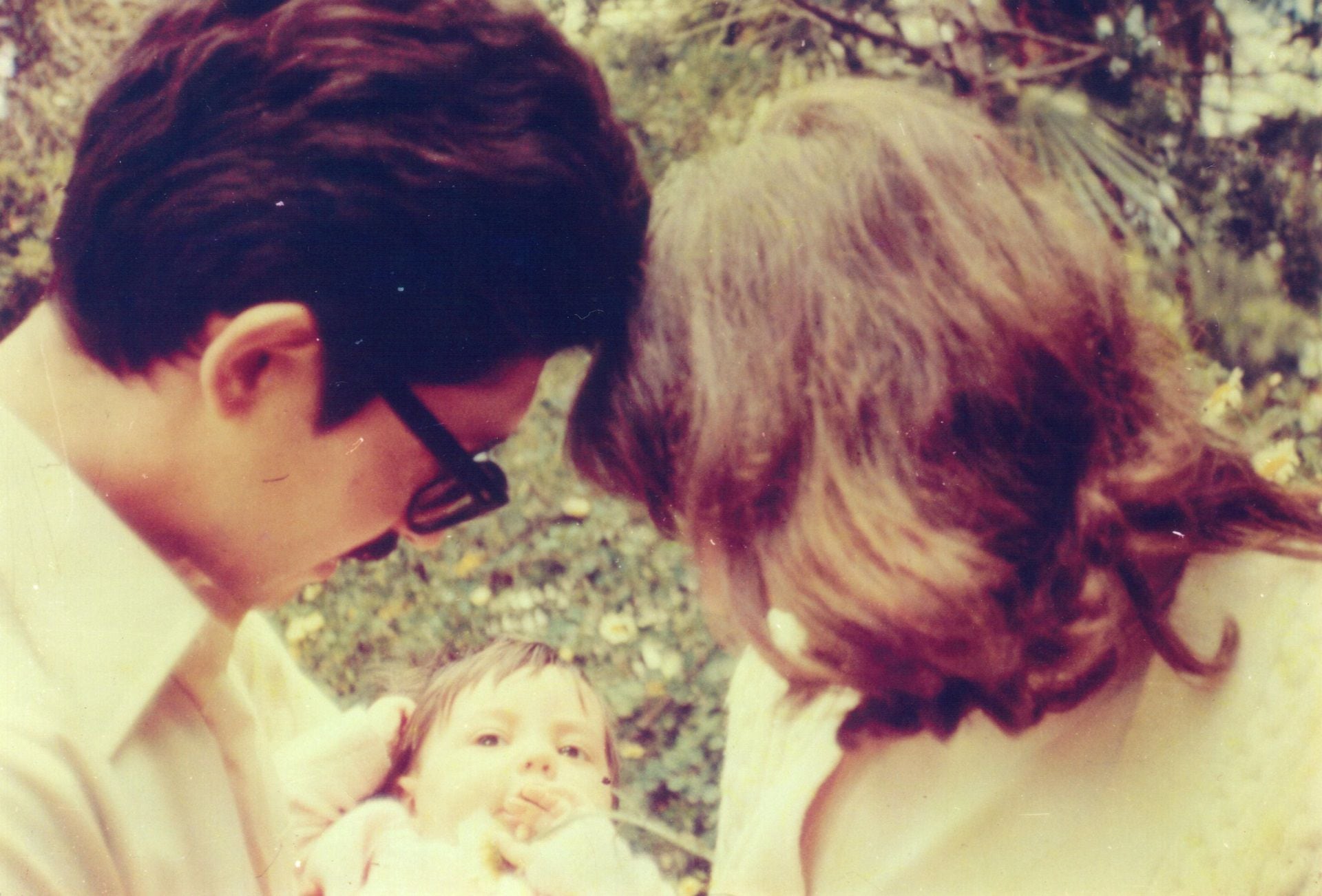

However, that June 14, 1972, when it was very cold and a terrible rain came out in the middle of the morning, Diana and Daniel still had no contact with the guerrilla organizations. The groom got up early, as usual, had breakfast and put on a tight dark suit, Bremer vest, a white shirt with a matching tie and loafers with a thin toe: a wardrobe not unlike the one he wore to go to college. Diana did not marry in white or in a dress with a long train and princess ruffles that were worn by the fiancees who used to go to see Bernardo years before, when they listened to the wedding march in the old organ of the Church of the Sacred Heart. A bride, a girlfriend! , his little brother shouted when he listened to the first chords of “Ave Maria” from the courtyard gallery. Diana put what she was doing on hold, grabbed him by the hand, and they ran the block and a half that separated her house from the temple to witness the weddings of unknown bride and groom. Bernardo looked at those white fairies with fascination and was enchanted by the sound of the piano. It was the adolescent times, when Diana still dreamed of being the heroine of the children's stories she read, the recipient of “Eu Te Darei o Céu”, by Roberto Carlos, or of the songs by Joan Manuel Serrat that they listened to on the old Winco record player with her sister Lili. From those evenings of the sixties to that of her wedding, time had passed leaving marks, and the things that mattered to her had turned. I was 21 years old, I was about to travel four months to a country with a revolution going on, and there was no time for frivolity. That is why, that day, he chose to dress up with a simple blue blazer, the knee-length skirt of the same color, black shoes with little heel and a white scarf with a knot around the neck, in the manner of children explorers. She wore her hair down below her shoulders, with natural undulations: the planchita, which had been essential so many weekends of her teenage years, was also left behind.

The religious ceremony was held in Nuestra Señora del Valle parish, presided over by priests José María Montes and Juan Carlos Ruta. It was spontaneous and unusual, because the bride and groom helped in the liturgy. Then, in the midst of the storm, the two families accompanied the newlyweds by caravan to the airport where they boarded the flight to Santiago de Chile. That night, when she closed the door of her house, Chicha felt absolutely alone. His son and daughter-in-law would spend the next four months on the other side of the Andes, and Pepe was focused on the upcoming string quartet tour of Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Honduras, Mexico and New York. He spent the whole day locked up in the attic, rehearsing in the morning and listening to recordings and deciphering scores in the afternoon. Chicha channeled her energies into the only responsibility she had left: the Lyceum classes”.

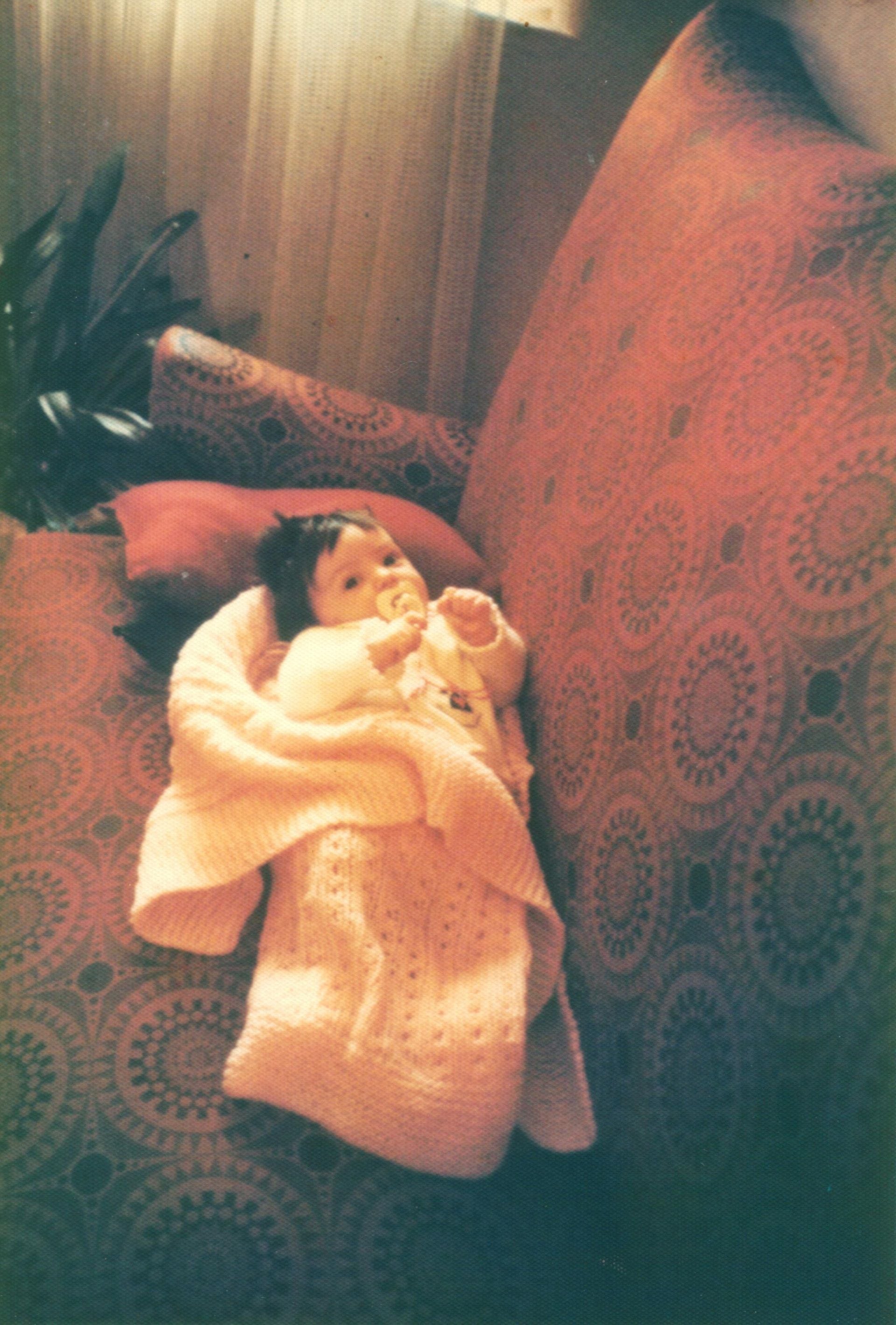

The personal and intimate portrait of María Isabel Chorobik de Mariani, Chicha, founder and second president of Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, who died in 2018, is the novelty of the collection of Mirada Crónica by Leila Guerriero, edited by Tusquets, and which this medium carries out exclusively. Laureano Barrera's book begins in November 1976, with the episode of Chicha's birthday, and ends more than forty years later, with his death. In the center, one of the most sinister events of the military dictatorship. On November 24, 1976, a task force attacked the house in the city of La Plata where his son Daniel Mariani, his daughter-in-law Diana Teruggi, both Montoneros militants, and their daughter, a three-month-old baby named Clara Anahí, lived. Diana died in the attack, the baby was kidnapped and Daniel, killed less than a year later. That search, that of her granddaughter Clara Anahí, was the turning point that turned Chicha Mariani into “an ordinary and wild woman who began to go through an extraordinary life,” according to Barrera.

Starting in 2014, and with more than 40 hours of interview, Laureano Barrera visited Chicha at his home every fifteen or twenty days, with the idea of writing a long text about his childhood in Mendoza. She took the opportunity to organize her memories and from there the mission of máxima was modified in a review of her life. Between talk and talk, the author found, with amazement, that his genealogies - that of the founder of Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo and hers - crossed a century ago. “Our common ancestors were a formidable starting point for the story, but they couldn't be the limit. Only then did the original impulse take the form of a book,” Barrera says.

Thus, for instance, the journalist returned to those events so often told, not so different from that of other mothers and grandmothers who lost children and grandchildren during the last military dictatorship. As in the emblematic house of rabbits that Laura Alcoba masterfully represented in her novel, the one that motivated one of the most sanguinarians commanded by the head of the police force, Ramón Camps, and his right hand, Miguel Osvaldo Etchecolatz, with more than 100 troops and a shooting that stunned a city. In fact, a treasure of militancy was hidden in the house on Calle 30 in La Plata: “Evita Montonera”, the official magazine of the organization, was printed there. Daniel Mariani -Chicha's son- and Diana Teruggi -his daughter-in-law- were in the Montoneros Press area, and they also coordinated the distribution, making it reach the largest number of colleagues. As a screen, the site appeared to be a rabbit farm, but it was, in fact, a clandestine printing press that was accessed through a sophisticated hidden mechanism.

Laureano Barrera, in his reporting, accessed unique details to approach the story from a new way of telling it. “The dawn of November 24 is for Daniel Mariani and his wife Diana Teruggi like any other: there are no signs of danger or premonitions that force them to alter the routine. They wake up around seven o'clock, with the first cry of Clara Anahí. Daniel, who was always an early riser, puts water in the kettle while Diana warms up a bottle of powdered milk (...) Sometimes Roberto Porfidio joins, who has been sleeping in the back room for a month. They know him by the name `Abel'. Abel was born in Necochea, received in La Plata as a professor of Letters and is now torn apart. A month ago, Mariana Beatriz 'la Negrita' Quiroga, a graduate in Philosophy and mother of her ten-month-old baby, Maria Cecilia, was killed. Abel wandered around different houses until he landed in Diana and Daniel's service room. In addition to the silent mourning forced by clandestinity, he had to get away from his daughter, because in the house of the Mariani-Teruggi family there cannot be two babies (...) At that time in the morning, they probably bought the newspaper El Día at the kiosk on 31st Avenue and you know that 'the Joint Forces shot each other in Toulouse with seditious' and that hazardous materials were seized in two headquarters of the Workers' Power. They work on counterinformation and detect with a clinical eye the almost textual reproduction of the cables that the Armed Forces send to the newsrooms. They know that the siege is great.”

More than a biography, Barrera's is an in-depth profile of Chicha Mariani, a long-winded look at a 42-year struggle in the search for her granddaughter, Clara Anahí. How a woman was troubled by her life as a professor of Art History at the Liceo School of the National University of La Plata and, after the massacre, she knew that her granddaughter was alive and began to search for her frantically, in solitude, with her husband working abroad and communicating through letters. About how Chicha had to abandon the lifestyle of a simple woman, who divided her time between teaching and dinners with friends, concerts, plays and art exhibitions in the capital of Buenos Aires, to head to find her granddaughter. How he began with his incessant inquiries in police offices, courts, churches, hospitals, political offices and the media. “When I was just 60 years old, I visited courts and spoke daily with lawyers, officials and leaders from all over the world, but I hardly went to the theater or visit friends anymore,” Barrera writes in a section of the book.

The work also traces the beginnings of Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo, the pilgrimage of these women through international organizations to gather support and at the same time denounce the horror of the dictatorship before the eyes of the world. It also recalls the creation of the Genetic Data Bank, one of Chicha's most paradigmatic creations, responsible for obtaining and storing information to determine cases of filiation of children of disappeared persons. Chicha had read a note in a diary, kept it, then met scientists from all over the world: without her arduous and persistent conviction, science would not have advanced.

Along with the review of files, personal letters and diaries of the time, Barrera does not avoid the approach to counterpoints in Chicha's life, such as the appearance of an alleged Clara Anahí , who later turned out not to be the granddaughter sought; such as the complex and tense relationship with her husband, the outstanding conductor and violinist Enrique José Mariani; or the estrangement with Estela Barnes de Carlotto, which culminated in Chicha's resignation from Abuelas through a public letter and after which, in 1996, he founded the Anahí Association.

“I met Chicha in her last time of life,” Barrera tells this media. She was lucid, she was sharp and at the same time serene, she always had a precise phrase that put things in their place. Understanding who Chicha had been and what her daily life was like as she traveled the world to find her granddaughter, that was the challenge of this book.”

Chicha Mariani's fears, routines, weaknesses, contradictions and strengths: not only her achievements or her idealization as an example of life. “As I put it in the book, it was an ordinary woman who did extraordinary things. The figure of Chicha is known in La Plata but has not yet been recognized as it should be, it is rare that she is not remembered in the country every March 24 beyond the acts in the house on 30th street. Chicha opened paths, such as the creation of the Genetic Data Bank. I tried to place it, in its proper dimension, as a woman who, with her pain and courage, twisted the recent history of this country.”

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies