The Bank of the Province of Buenos Aires celebrated its two centuries of existence in January, beginning a jubilee year. Beyond the announcement of literary and artistic competitions, and an exhibition of objects and furniture in Mar del Plata, of its welcome initiatives, it seems that such an event calls for a commemorative program of categorical historiographic density, which allows critically questioning those origins, in that year 1822 environmentally “rivadaviano”, when the profile of the institution looked so different from the evolution it soon acquired.

The official commemorative speech has predictably placed the emphasis on the bank's current status as a public bank, ignoring that fact, which might sound uncomfortable to the ears pleased in the advocacy of statism as an exclusive engine of general welfare, that it was born as a private bank and that its initial capital was integrated by Argentine and foreign shareholders, mostly English among the latter. But the past is irreversible and, even detached from any empathy, it should not bother anyone, when it is objectively weighted and in the proper epochal perspective. On the other hand, it seems unreasonable to deny a priori private entrepreneurs of two hundred years ago a genuine inclination for the common interest and progress of the nascent country.

It is appropriate to recall some antecedents that, at the time, rigorous historians such as Alberto de Paula, an official of the institution for almost half a century and, undoubtedly, its senior chronicler, together with Noemí Girbal-Blacha and other researchers (Nicolás Casarino, among the classics) and agents of the establishment, highlighted and they disseminated.

Talking about the origin of the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires is almost the same as talking about the birth of national institutions, because its creation was, to some extent, a necessary sequence of the revolutionary program of May 1810, verified at that precise moment of consolidation of liberal and anglophile ideas that can be summed up in the political rise of the figure of Bernardino Rivadavia.

Let's go back in time and on the map. It could be said, to begin with, that Western monetary developments reached its point of greatest innovation when, at the end of the 17th century, the Bank of England issued the first convertible banknotes, and then, at the beginning of the 18th century, when the banknotes issued by the bank devised by John Law or Bank were forced into force in France General Privado (later Banque Royale).

The Scottish theorist Adam Smith, in his backbone work, The Wealth of Nations, advocated the replacement of gold and silver with paper values, giving prominence to banknotes issued by banks and bankers.

Sooner or later, these ideas were going to reach Spain and its overseas domains, because in the metropolis the principles of this new science, which was political economy, were fiercely debated. Manuel Belgrano, a student in Salamanca, was a witness and participant in that debate. Upon returning to Buenos Aires, full of updated readings, he was appointed secretary of the Royal Consulate, which was the institution that governed trade and industry in the Viceroyalty.

On the other hand, the depletion of the Argentine deposit of Potosí caused the shortage of metal coins, both in Lima and in the Rio de la Plata, which had to be replaced by other means of payment, such as those small silver discs marked by their issuers, whether they were warehouses, bakeries or shops.

In addition, the war of emancipation, while requiring enormous financial efforts to cover military expenditures, generated a significant outflow of foreign capital from the port of Callao. The scarcity of resources was pressing. The costs of the war were covered by the government through loans guaranteed with promises of payment that assumed the formality of Treasury bills or promissory notes.

The architects of the May Revolution had adopted the monetary theories in vogue, which favored hypothetical bank credit as a dynamo of industry and commerce. In 1811, the Triumvirate asked the Consulate to call a group of local and foreign capitalists to form a maritime insurance company and a discount bank.

In 1818, the National Fund Fund of South America was created, which was a far cry from being a bank, because it did not grant loans, nor received deposits, nor did it make money orders, nor deducted bills of exchange. Rather, as De Paula pointed out, it was a sui generis loan to sustain a literally “war” economy. It lasted until 1821.

The truth is that the financial burden of the independence war effort was borne by Buenos Aires, without significant external support or retribution from those other American states that it emancipated. In other words, a continental brotherhood that is well proclaimed but little and not supportive, when it comes to paying the bills.

As the British Consul Woodbine Parish put it, it was truly “astonishing” that the Province did not succumb to these brokenness. A concept that could well be withdrawn for other periods of Buenos Aires history, signified, no longer by war, but by the deficit caused by bad administrations.

In May 1821, English professor Santiago Wilde (who was a member of the Finance Commission created by the Chamber of Representatives) proposed the creation of a bank with capital of one million pesos to be signed by traders, capitalists and real estate owners. The institution would have the power to issue paper money and put it into circulation, as well as to grant credits for the promotion of industry and commerce, and to operate in the insurance sector. In November of the same year, the Public Credit and Amortization System was created.

As can be seen, the previous steps were taken for the emergence of a relevant banking institution, while the ideological environment was maturing for it. We thought of a banking model with private participation and strong political support from the Province.

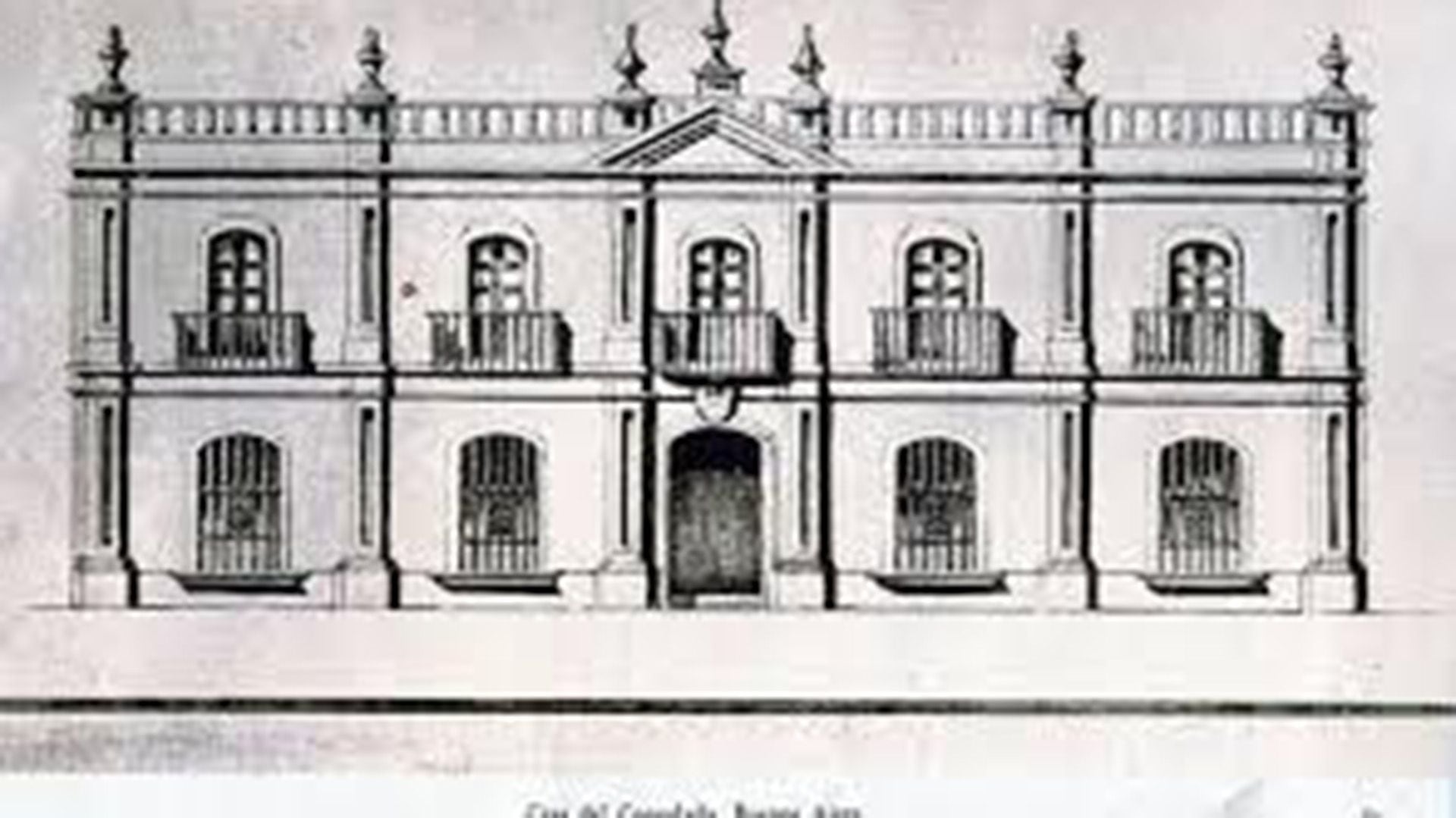

With these premises, Dr. Manuel José García (son of the preclaimed Colonel Pedro Andrés García, our first national cartographer), who was governor Martín Rodríguez's finance minister, gathered potential investors at a meeting held on January 15, 1822 in the premises of the consular house, located on San Martín Street No. 137 (a foundational topographical mark that the Bank later recovered and preserved, although changing the architecture of the building twice, until today).

At that first meeting, it was decided to create a “swing bank” (instead of a “discount bank”) whose capital was subscribed by private shareholders. The fact is, I insist, relevant from the point of view of history, because, in general, the “statist” story is often omitted with retrospective scruples. It was born as a private limited company.

The founders were present, chaired by Minister Garcia, who appointed a committee to draft their statutory letters, composed of Pablo Lazaro de Berutti, Diego Brittain, Féliz Castro, Juan José de Anchorena, Guillermo Cartwright, Juan Fernandez Molina, Sebastián Lezica, Roberto Montgomery, Miguel de Riglos and Juan Pedro de Aguirre.

To the second assembly, held almost a month later, on February 23, in the same building, were added Juan Alsina, Nicolás de Anchorena, José Julián Arriola, Juan Bayley, Francisco Beltrán, Marcelino Carranza, José Marcelino Coronel, Braulio Costa, Guillermo Hardist, Juan Harrat, Juan Miller, Guillermo Orr, Guillermo Parish Robertson, Marcelino Robertson, Marcelino Rodríguez, José María Roxas y Patrón (who, in addition to being a merchant with extensive experience in Brazil, was a doctor), Francisco Santa Coloma and José Thwaites. They were, so to speak, the most pomegranate of the Buenos Aires trade, alternating Argentine and British businessmen. At that meeting, a draft statute was discussed, published by El Argos and La Abeja Argentina.

With both assemblies (founding the first, and giving statutory legal content the second) it can be said that the Banco de Buenos Aires was created, to whose bases other investors immediately joined. Of these, the third were British, but the Germans Carlos Harton, Juan Zimmermann and Luis Vernet (years later, the first Argentine governor of the Malvinas Islands), the American Diego Robinet, the Italian Domingo Gallino, the Greek Juan Comonos and the French firm of Roquin Meyer Mores & Compañía also participated. Almost a mosaic of foreign nationalities that thrived in the river plate trade and already expressed an early diversity of migrants. Let us remember that since the beginning of 1821, foreigners of Protestant rite even had their own cemetery in the block of the church of Socorro. They came mainly from Great Britain, from some German enclaves such as Prussia and Hanover, or such as Bremen and Hamburg, and from the United States of America. In the beginning, it was common for Creoles to confuse Germans and Americans with the English, especially in port areas.

The traveler, author of the testimonial chronicle Five Years in Buenos Aires, was able to point out in those years “the multitude of Englishmen dedicated to retail: on Calle de La Piedad they have numerous shops where all sorts of items are sold. At the head of business, it is common to see inscriptions such as: English shoemaker, tailor, carpenter, watchmaker etc. The number of British subjects scattered throughout the country who are engaged in tannery, agriculture and other tasks, is more numerous than you might think...”

It is estimated that by 1822 the British subjects living in Buenos Aires numbered 3,500, while the Germans would not exceed 600 residents. Many Englishmen had married Creoles and, as the aforementioned traveling chronicler said, “from what I see they have not regretted it...”

Following our account of the founding of the Bank, with the subscription of shares almost reached the statutory number of 300, it was time to provide the corporation with a collegiate governing body or board, for which a third assembly was held, on March 18, 1822 (that is, two hundred years ago these same days). The following nine shareholders were elected by a majority vote: Juan Pedro de Aguirre, Juan José de Anchorena, Diego Brittain (much of their land gave rise to La Boca), Guillermo Cartwright, Felix Castro, Juan Fernandez Molina, Sebastián Lezica, Roberto Montgomery and Miguel de Riglos. They were given power to start operations immediately, without needing to reach the exact number of three hundred shares.

On March 20, 1822, the first meeting or “board” of directors took place, who elected Cartwright as president and Lezica as secretary. However, the incumbents did not accept them definitively and then, in July, Juan Pedro de Aguirre and Sebastián Lezica were appointed respectively. Aguirre presided over the Bank until 1824 and resigned in conflicting circumstances that we will explain shortly.

Also in July 1822, the first employees to take up their duties in August were appointed: Enrique Thiessen, Guillermo Robinson, Pedro Berro, Pablo Lazaro de Berutti and goalkeeper Nicolás Uriarte. As Alberto de Paula pointed out, the selection of this first staffing should not have been easy, as there was no history of a bank house on our land.

Since its origin, the Bank obtained numerous privileges: the law of June 26, 1822 granted it the “grace” that for twenty years a similar institution could not be created in the Province along with other tax advantages and exclusivities, such as judicial deposits.

During the debate on the law, Ministers García and Rivadavia had been present in the Chamber of Representatives, who defended with emphatic arguments the granting of privileges, which in turn were objected to by some legislators of the federal bloc, such as Manuel Moreno and Juan José Paso. Interesting is the argument made by Paso (the former secretary of the Junta de Mayo) that the twenty-year ban on installing another bank prevented the creation of a similar credit institution, but supported by the artisan sector, for example, which would amount to the current “SMEs”. In turn, Moreno defended competition as a virtuous element of the market, to which Garcia responded with a praise of exclusivity, based on the example of the Bank of London. Obviously, the British models exerted their powerful influence on a minister who history would prove to be very sensitive to such an influence.

The debate ended with the compromise formula devised by Deputy Julián Segundo de Agüero, to use the concept of “grace” in terms of the impediment of the existence of a competitor for twenty years. However, three years later, as De Paula pointed out, Rivadavia and García themselves would force the effort to nationalize the entity. Interestingly, this progressive state interference, which seemed to displease domestic and foreign shareholders alike, resulted in the departure of Argentine holders, while the British remained who came to buy shares of their outgoing colleagues. Even a director elected as president in 1824 (Juan Pablo Sáenz Valiente) refused to take office and resigned from his chair, believing that, as he said, “in the Bank foreigners exert a pernicious influence on the country, to whose abuse he did not want to contribute...” Shortly afterwards Mariano Sarratea, José María Roxas and Patron and Miguel de Riglos. An internal crisis began, which would also result in the resignation of President Aguirre himself.

An explanation of these tensions where a sense of “national interest” emerges could be found in the fact that the government did not plan to allocate the funds of the loan contracted in England for peremptory public works (which had been the substantive argument at the time of obtaining approval for the operation), but to open balances in London in favor of Buenos Aires' foreign trade, thus increasing imports and customs collection.

But let's go back to 1822: if there was anything missing from the brand new institution, it was to have its own headquarters. To this end, the board requested the Government to occupy the so-called Temporality Houses, located in the Block of Lights and built on the old vegetable garden of the Jesuit Fathers school in San Ignacio. They were buildings of enormous solidity, as evidenced by the standing of their premises in Peru 272 and 294. So before the end of 1822, and after some renovations, the Bank began to occupy those spaces, sharing the income with the Representatives Hall. Pine desks and chairs and a large mahogany table for the directory were the first furniture, to which iron boxes for the flows, counters and shelves were added. Customers would be arriving little by little.

This was the beginning of the biography of the first Argentine bank and the oldest bank in Latin America, the forerunner of credit and currency (it printed the first national banknote), according to a well-known institutional slogan. A couple of years later, in 1824, the entity would go on to administer that controversial loan contracted with the Baring Brothers House in London, which did not arrive in cash but in bills of exchange, and which many point to as the beginning of Argentine external indebtedness. But we can continue talking about this and other chapters in the history of the Banco de la Provincia de Buenos Aires throughout this jubilee year.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies