In Ecuador, targeted shark fishing is illegal. An executive decree signed in 2007 established it, however, a caveat was included: if shark fishing is incidental (by chance), its parts can be marketed. It has been 15 years since the issuance of the decree and shark fishing has not decreased, on the contrary, it remains at the same levels as before the signing of the regulations. Paradoxically, the export from Ecuador of shark fins, one of the most desirable parts of the shark on the international market, especially in Asia, has tripled in the last year.

According to the Abrams World Trade Wiki platform, Ecuador is among the 10 countries in the world that sold the most shark fins between 2020 and 2021. It also appears as the fifth emerging market and shares high market shares (6.33%) along with countries such as Spain (10.90%), Hong Kong (10.23%) and Mexico (6.20%). Between January and September 2021 alone, according to the National Customs Service of Ecuador, 223 tons of shark fins worth USD 6.5 million were exported. In 2013, the oldest year in which public data are recorded by the Customs Service, barely 75 tons of fins worth USD 646,4333 were exported. 78% of fins exported in 2021 were four shark species protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).

In 2021, the specialized environmental portal Bitácora Ambiental already warned about the “laundering” of shark fins between Ecuador and Peru and denounced that “the authority does not monitor compliance with fishing classified as incidental”.

In the last two years, Ecuadorian shark fins have only been exported to Peru. In the neighboring country, the fins are re-exported to Asia. Even, according to the portal specialized in environment Mongabay, “Peruvian and Ecuadorian authorities have identified, for some time now, that there is a wildlife trafficking route that starts in Ecuador, passes through Peru and ends in Asia”. According to a WWF study, the sixth largest flow among shark traders is from Ecuador to Peru. Shark fins are very popular in regions such as Hong Kong, where shark fin soup can cost between 100 and 200 dollars.

Incidentality as a smokescreen

Lack of control is one of the main concerns of shark conservation activists. Cristina Cely is director of the environmental organization One Health Ecuador and managed to get a discussion in the National Assembly about the temporary ban on the commercialization of shark fin by-fishing, although in the end the proposal was not approved by Ecuadorian legislators. Cely told Infobae that the increase in fin exports is due to the fact that shark fishing has been encouraged and argues that not only is the capture of these species targeted, “but we are also talking about trafficking.”

On his Twitter account, Cely actively denounces that Ecuadorian authorities are not implementing actions capable of combating trafficking in these species: “Sharks are one of the most threatened species in the world and their trafficking involves even Ecuador. However, Ecuador continues to leave them defenseless and protect traffickers,” he wrote.

Cely told Infobae that shark species are being exported illegally: “There will be shark species that are exported like others.” The environmentalist says the latter in relation to seizures of hammerheads in Peru. However, seizures would be a minimal sample of trafficking in this species. The environmental lawyer, César Ipenza, told Bitácora Ambiental that “in the illegal trade in fins, seizures represent approximately 10% of the volume of the business, because there is no constant control”.

The last seizure of hammerhead sharks in Peruvian ports occurred in July 2021, where authorities found nearly a ton of hammerhead sharks from Ecuador, despite the fact that catching — including incidental — and marketing of this species has been banned since 2020.

On February 9, Peruvian justice condemned shark fin traffickers for the first time. The sentence ruled four and a half years in prison and civil reparation of 106,375 soles (about 28,000 dollars) against the deputy manager of the company Ajansa Peru (owner of the cargo) and the buyer Poly Diks Pinto Gonzales. In 2018, those sentenced had trafficked, from Ecuador, 1.8 tons of fins of different shark species, including pelagic fox, common hammer, smooth and silky shark. All threatened with extinction and protected by CITES.

When fishermen land their fish in the port, an inspector from Ecuador's Ministry of Production must assess whether the landed product corresponds to the legal fishing of the caught species. It is the inspectors who issue a certificate attesting to the legality of, for example, shark by-fishing. That document allows the fisherman to sell what he caught.

However, fisheries inspectors are often absent or prefer to avoid problems and intimidation, so lack of control has become the rule. An investigation by Diana Romero, published in GK, includes the testimony of a former fisheries inspector, who claims that massive landings of hammerhead sharks — a threatened species, including incidental fishing — were made in Manta, a coastal area of Ecuador, especially during the early morning. The former inspector told the journalist that “as a human being, I'm not going to risk my life reporting it or doing a big operation.” Those who denounce illegal fishing are then persecuted.

According to the Mongabay portal, illegal fishing is the third most lucrative illicit activity in the world, after drug trafficking and arms trafficking.

Mauricio Castrejón, a doctor in marine biology specializing in fisheries management and evaluation, explained to Infobae that a fishing inspector who is not well trained could confuse the shark species that fins come from, but a fisherman could not. Castrejón says that if there is some “type of corruption, they could be letting other species through there”.

Although it is considered that only incidental shark fishing is allowed in Ecuador, the catch levels of these species remain the same compared to fishing levels prior to the decree prohibiting targeted fishing. In addition, the export of shark fins has increased and landings show the same shark species, which coincide with the most desirable in international markets. Castrejón raises several hypotheses about this, one of which is that shark catches are not incidental but represent illegal fishing actions specifically aimed at these species.

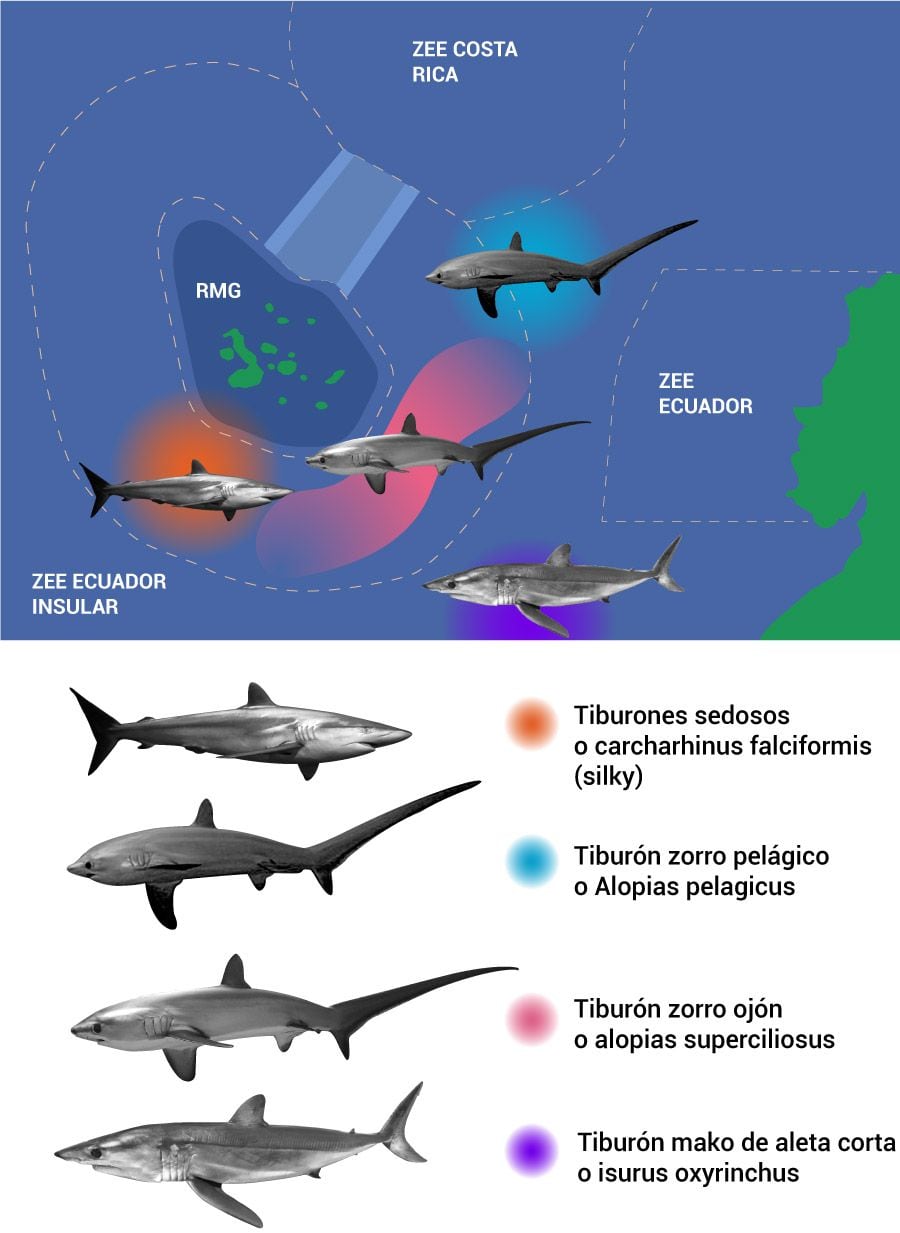

Jorge Ramírez is a marine biologist and coordinator of the fisheries management project of the Charles Darwin Foundation. Ramírez agrees with Castrejón's thesis: “By regulations, there is no targeted fishing for sharks in Ecuador, everything is incidental, although in practice it is seen that there is fishing aimed at sharks where they catch several species,” he explains. The biologist indicates that fox, mako and silky sharks — the most exported in 2021 — “are highly migratory (species) so they do leave the reserve. This causes these species to be exposed to being caught by fishing fleets outside the Galapagos marine reserve either incidentally or in a targeted manner in case of international waters.”

In Ecuador, it is not yet defined what maximum level of shark fishing can be considered incidental. Although the Regulations of the Organic Law for the Development of Aquaculture and Fisheries were officially signed on 25 February 2022, the regulations do not establish the maximum percentage of shark fishing that can be considered incidental, but instead derive that responsibility to the Management Plan for Aquaculture and Fisheries and the Institute Aquaculture and Fisheries Research Public. Establishing this precision is urgent as experts say that, under the excuse of incidentality, thousands of sharks continue to be caught in Ecuador.

Fishing gear and incidentality

Longline is one of the most used fishing gear on the coast of Ecuador and the world. It consists of a horizontal floating line, usually made of a synthetic thread, that can measure tens of kilometers and from which vertical lines are born that carry thousands of circular hooks at their ends. According to Bruno Leone, president of Ecuador's National Chamber of Fisheries, longline generates an incidentality of up to 20%.

Castrejón explained that the bycatch of the longline will depend on the configuration of this fishing gear and the depth at which it is located: “There are certain longlines that are configured to catch sharks,” he says. The expert says that these longlines have metal queens (a type of rope from which the hooks hang). This element is crimped into the shark's teeth, attaches the fish to the longline and prevents it from breaking the fishing line. For example, Pablo Guerrero, from the WWF of Ecuador, says that there is a season, between April and October of each year, where the longline fleet fishes tuna and weevil, but due to the type of fishing gear, incidentality increases: “During this period a long line called “thick”, of medium water, designed to catch tuna and weevils, but sharks are also caught in percentages that are around 30 — 35 per cent of the total catch.”

There are other fishing systems that trap sharks and are used in Ecuador. For example, the Ecuadorian tuna industry has the largest fishing fleet in the Eastern Pacific Ocean and uses seine nets among its procedures, according to the WWF. This fishing gear captures the fish by surrounding them on the sides and in the bottom. According to Leone, the incidentality generated by this system is 1.8%, although ship crews are trained to release sharks and sea turtles that fall into the net.

Instead, the trawl forms a kind of cone that is towed from a boat, keeping it open to catch everything in its path. Trawling is the most damaging to the oceans and generates high rates of by-catch, according to Greenpeace.

Castrejón explains that by-catch depends on some elements such as fishing gear and depth. But also, as Alex Hearn, doctor in marine biology and professor at the San Francisco University of Quito says, it will depend on the time when the fishery is carried out. Fox sharks, mako and silky at night are located closer to the sea surface, if the fishery is done after sunset, the boats have a better chance of catching these sharks.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs