In mid-March 1976, the days of the government of María Estela Martínez de Perón were numbered and few. Few knew exactly the date of the coup that would overthrow her, but no one escaped that it was imminent. In downtown Buenos Aires, Corrientes Avenue, with cinemas, theaters and restaurants open, maintained a false routine of normality despite the ominous presence of the Ford Falcons with diffuse patent plates and watchful eyes inside it that traveled at a speed that barely exceeded the pace of man.

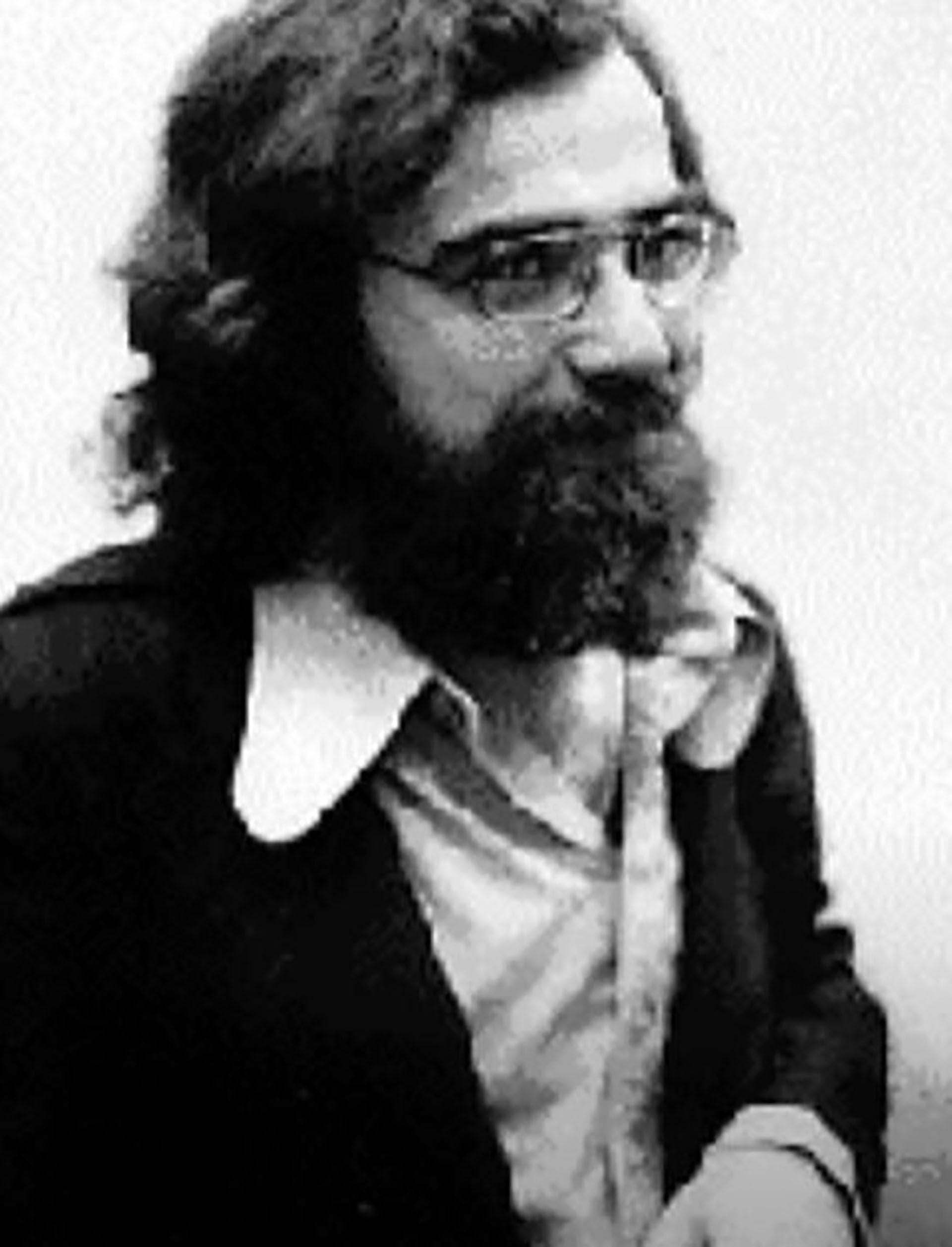

At that time, the series of three recitals by Vinicius de Moraes and Toquinho in the Gran Rex stood out on the show list, the last stop of a successful tour that had included presentations in Punta del Este and Montevideo. The two monsters of Brazilian music were accompanied by “Azeitona” on bass guitar, “Mutinho” on drums and Francisco Tenorio Cerqueira Junior, a pianist who at the age of 35 was already considered one of the best exponents of samba-jaz. “Manos de oro, author of remarkable talent and enormous future”, was written about him by Ruy Castro, one of the most renowned critics of bossa nova and Carioca culture.

The early morning of Thursday 18, after the recital and late dinner in a restaurant, the band members extended the evening at the Normandie apart hotel, in Rodríguez Peña 320. They had been joined by Renata Schusseim and the poet Marta Rodríguez Santamaría, Vinicius' girlfriend.

At three o'clock in the morning, Tenorinho — as Vinicius called the pianist — found not without unease that he had run out of cigarettes. Luckily they were in the center, a few meters from Corrientes Avenue, where there were kiosks that never closed.

“I'm going to buy tobacco,” he said before leaving.

Tenorinho, who did not have any political activity, took to the streets and it is possible to imagine it: a skinny man, with a beard and long hair, with the air of an artist or an intellectual, who walks along a path of Rodríguez Peña and flows into the avenue of lights in search of an open kiosk. You may not have imagined that in Argentina in 1976 that image, your own, matched the stereotype of the left-wing militant or, translated into repressive jargon, that of a “subversive criminal”.

The kidnapping of a pianist

Already over currents, Tenorinho spotted a kiosk and started walking towards it. He didn't come. He was intercepted by a patota of four armed men who got out of a Ford Falcon and forcibly lifted him up. The newsstand, from about forty meters, saw the whole scene. It did not occur to him to intervene, or even to shout: in Argentina of the State terrorism that preceded the coup ordinary people did not do such things.

Around the same time that Tenorinho was taking to the streets, Vinicius de Moraes announced that he was going to sleep and Toquinho went to another room in the apartment. I was tired. In none of the accounts of what happened that night is it clear who told Vinicius' guitarist and co-team player that something had happened to Tenorinho.

At 3.20 in the morning the telephone rang in the apartment of the apartment that Vinicius occupied. Only Renata Schusseim and Marta Rodriguez Santamaría were awake. It was Toquinho, who in a desperate voice asked to speak to Vinicius, he would not say anything to women.

Still half-asleep, the poet grabbed the tube and took it to his ear. The Women heard him say two things: “Oi, Toquinho!” and then, “Shit!” He hung up and stood there, as if he was absent.

-Vina, what is it? - he asked him.

“Tenorinho... Tenorinho disappeared,” Vinicius answered him like a ghost.

The desperate search for Vinicius

In addition to being a poet and musician, Vinicius de Moraes had diplomatic experience. That same night he asked for a phone book and called every hospital in the city to no avail. The next morning he sought a lawyer and filed a habeas corpus. He contacted a former son-in-law, who was a Brazilian consul in Buenos Aires and asked him to move quickly.

That same day he also went to the Brazilian Embassy and met with the ambassador, Joao Baptista Pinheiro, who promised him that he would ask for information at the highest levels of government. He later called on all the journalists and politicians he knew, so that Tenorinho's disappearance would take public status. I sensed that it might help to find him.

That night, exhausted, he collapsed. “We were all in shock. Vinicius was thoughtful and self-absorbed, it was part of his personality to react like that when something overflowed him. There was no answer and sadness was abysmal,” Marta Rodríguez Santamaría recalled many years later.

The poet's last hope was that Tenorinho had been arrested because he had forgotten his passport in the room — he had been found that same night, in the nightstand drawer — and that he was in a police station. That there he could clarify the situation and be released. It had been reported that the police could hold a person for 48 hours for background checks. That's what the law said, but in March 1976 in Argentina that law was wallpaper.

On March 24, the coup occurred and a few days later, desolate, Vinicius returned to Brazil.

Tenorinho never showed up.

Victim of Plan Condor

Despite his political and diplomatic contacts, Vinicius did not know that the repressive apparatuses of Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Uruguay and Brazil had long been working in coordination of the illegal repression against political and social dissent in all these countries. They exchanged information and even, by then, began to transfer detainees from one country to another.

Brazilian Ambassador Joao Baptista Pinheiro never told Vinicius that his efforts to his Argentine contacts had been answered. A source in the Navy told him that he was being held, but he did not offer to return the pianist — he was dead by then — but to pass on the information they had obtained from him.

“The Brazilian military knew Tenorio's fate, but they were hiding it. There are documents found in the archives of the Brazilian political police, the DOPS (Directorate of Political and Social Order), which refer to a message addressed by ESMA to the Brazilian embassy informing them of the death of the pianist, who has been kidnapped and tortured since March 18. Because once they recognized that they had the wrong person, they could no longer set him free. It would have been a scandal,” confirmed years later journalist Stella Calloni, who thoroughly investigated the operation of the Condor Plan.

“He was killed by Astiz”

It took 37 years for details of the kidnapping and murder of Francisco Tenorio Cerqueira Junior to be known. The information was provided in March 2013 by an Argentine repressor then based in Brazil, Claudio Vallejos (a) “El Gordo”, a former member of the task forces of the Navy's School of Mechanics and one of the material authors of Tenorinho's disappearance in the early hours of March 18, 1976 on Corrientes Avenue.

Vallejos had escaped to Brazil a few months after the recovery of democracy in Argentina, when the laws of impunity known as “Due Obedience” and “End Point” still did not apply, to prevent the Justice from calling him to testify for crimes against humanity committed at ESMA.

In the neighboring country, they were fetched as much as they could to survive, almost always outside the law, until he was arrested for scams in 2012. That same year he accepted in exchange for money a lengthy interview with journalists from the Brazilian magazine Senhor, where he told his past as a repressor at ESMA with hair and signs. So much was said that the magazine had to divide the interview and publish it in two editions.

In December of that same year, Vallejos repeated his confession to the Truth Commission, created by President Dilma Rousseff, with the assurance that, protected by the Brazilian amnesty law, he should not answer for his crimes under the Condor Plan. I did not imagine then that the Argentine Justice would ask for his extradition.

“El Gordo” related that in the early morning of March 18 he was participating in an operation in downtown Buenos Aires when he was ordered to go and search with the patota that made up a suspect they had in a police station, a guy with a “half subversive aspect”. They transferred him to ESMA where, according to their statements, “he arrived alive and without being beaten”.

He also confirmed that Brazilian intelligence was aware of the fate of the pianist. “On March 20, 1976, Officer Rubén Chamorro, head of ESMA, requested permission to contact a Brazilian agent whose war code was 003, letter C and belonged to the Brazilian Naval Information Service, to inform him which task force was interested in providing information on the identity and political ties of Francisco Tenorio Cerqueira Junior”, Vallejos said in the interview.

In his confession, the repressor reported that Tenorinho was tortured, although he claimed that he had not participated in the interrogations. And he also provided the date on which he was murdered, March 25, and who was his executor:

“(Alfredo) Astiz killed him in the basement of the old ESMA building but I don't know where they buried him,” he said.

Vallejos died at the Bernardo de Irigoyen Hospital, in Salta, in June 2021. He was serving house imprisonment for his poor health condition. Shortly before he died, in the last few years, he confessed: “I killed at least 30 people and lost count of those I tortured and those I tortured and ended up dead.”

The memory of Tenorinho

In 2008, Brazilian director Walter Lima Junior released the film Os Desafinados, where he included as a tribute to the story of Francisco Tenorio Cerqueira Junior.

Another filmmaker, the Spaniard Fernando Trueba — director of Belle Époque and The Oblivion We Will Be, among other works — plans to release next year an animated film They Shot the Piano Player about Tenorinho's life, calvary and death. “I don't want to make a film about a missing person. It is more important to reconsider him as a musician,” he explained in a recent interview with the Spanish newspaper El País.

In Buenos Aires, Tenorinho has been remembered since 2011 with a plaque on the facade of the Normandie hotel. Under his name it says: “This brilliant Brazilian musician, a victim of the Argentine military dictatorship, stayed here.”

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs