On March 18, 1957 in Río Gallegos, the wind ran with its usual icy ferocity. In the dark, a group of men were waiting nervously for the arrival of the compromised car. One of them, Hector Campora, addressed Jorge Antonio, leader of the group, half-jokingly: “Jorge, why don't we go back to jail and leave this escape thing for another day?”

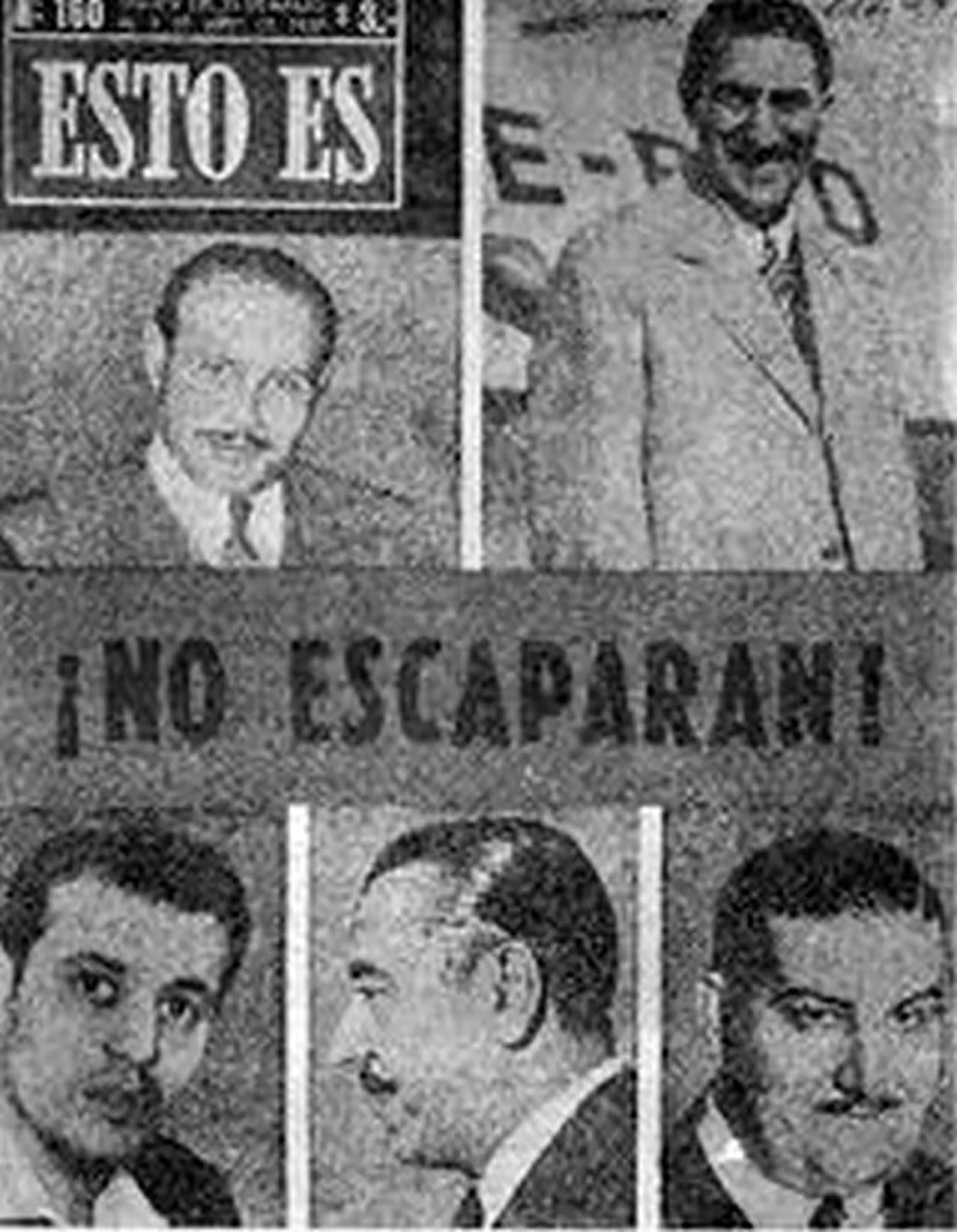

The fugitives from the Rio Gallegos Prison were Peronist leaders Jorge Antonio, Hector Campora, Guillermo Patricio Kelly, John William Cooke, José Espejo and Pedro Gomis. With them was their accomplice, the jailguard Juan de la Cruz Ocampo, who had facilitated their exit and also took care of closing the prison on the outside by taking the keys.

After a tense wait of several minutes, the yellow Ford arrived, led by Manuel Araujo, a friend and collaborator of Jorge Antonio. Eight men, some of them overweight, piled up inside the car. They had to travel 66 km to Monte Aymond, the border crossing, and then 200 km more to Punta Arenas, Chile.

A couple of kilometers before reaching the gendarmerie post, a collaborator stops them and instructs them to leave Route 3. The fugitives cut a wire and push the Ford - with the engine off - cross-country, making a semicircle to avoid the post. Jorge Antonio had accepted the request to add Gomis to the escape, because he was in good physical condition to help push the car for four km through the middle of the field. Two Peronist resistors remain in the prison: Juan Parla and Horacio Irineo Chavez.

According to Chilean newspapers, the fugitives passed through the two Chilean Carabineros posts - Punta Delgada and Río Pescado - without stopping. Possibly Rio Gallegos obstetrician Ramona Estévez de la Vega organized that part of the escape.

At the first light of dawn they arrived in Punta Arenas, where they were received by the mayor and stayed at the Hotel Cosmos, the best in the city. As planned, the fugitives asked for political asylum in Chile. President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo was a friend and ally of Juan Domingo Perón and southern Chile was the area where Peronism enjoyed the greatest sympathy, which is why the fugitives found much spontaneous collaboration. Obviously, as soon as he heard of the escape, the dictatorship of Lieutenant General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu requested extradition and the Chilean government was forced to arrest them until their legal situation was resolved.

The plan and the local partners

The main promoter of the plan was Jorge Antonio, who had the financial means to carry it out. The first step was to move her family from Rio Gallegos and with her two collaborators: Hector Naya and Manuel Araujo. They, pretending that they are going to set up a company in the city, begin to create a network of social relations. There, they integrate two key persons into the plan, Dr. Humberto Curci - the prison doctor and co-owner of the Río Gallegos Sanatorium - and the obstetrician of that sanatorium, Ramona Estévez de la Vega. Curci, with Araujo's money, buys the Ford car used in the escape. And Ramona, a convinced Peronist militant who had worked with Evita, will be the one who accompanies Araujo to Punta Arenas to make intelligence and contacts for the escape.

Jorge Antonio, from prison, was responsible for establishing good relations with the chief of the prison and the members of the guard. There was only one officer, named Macias, who was very hostile to prisoners. For the date of the escape, they sent a telegram from Ushuaia, informing Macias that he had a sick relative. Jorge Antonio got him the money to travel, and the guard was left in charge of Ocampo, who was already committed to the escape.

Another external participant was the rancher Leonidas Moldes, who had been Cooke's student at the faculty. Their participation consisted of making the police believe that the fugitives would go to hide during their stay, thus gaining valuable hours to reach Chile.

On the night of the escape, part of the wayward prisoners and some guards were asleep with sleeping pills that Kelly got. And with previously entered weapons and the collaboration of Officer Ocampo, they came out comfortably. To the point that Araujo's car took a long time to arrive, while the escapees waited in the street in front of the prison, without the alarm sounding.

Who were the fugitives

Businessman Jorge Antonio was Mercedes Benz's representative in Argentina and had grown economically during Peronism. He was a personal friend of Perón and syndicated as a contributor to the movement's political campaigns. Although there was no evidence, he was accused of corruption, imprisoned and stripped of his property. He refused to testify against Perón (as if some “repentants” did) and paid with two years in prison under the worst conditions.

John William Cooke had been a national deputy and one of the few leaders who led the Peronist Resistance, creating the National Command together with Cesar Marcos and Raul Lagomarsino. He was imprisoned in November 1955. From exile, Perón appointed him as the only head of Peronism in the national territory and as his heir in case of being killed. It was the only time in history that Perón appointed an heir, a sign that he feared for his life and it was necessary that in the emergence of his physical disappearance, Peronism did not turn into anarchy. In a letter to Leloir dated 10-03-57 Peron tells him: “How the attempts to assassinate me by the dictatorship came to me through his envoys, some of whom were arrested and others were running, put in danger that any day they could achieve their attempt, I sent Dr. Cooke a document declaring him my replacement in the event of death. Dr. Cooke was the only leader who connected with me and the only one who openly took a position of absolute intransigence, as I believe it corresponds to the moment in which our movement lives.”

This role of Cooke lasted until the failed agreement with Frondizi, who had him as one of its managers, and turned off his light within the movement. In 1973 and 1974 Perón repeated several times that “my only heir is the people”.

Hector Jose Campora, was an important Peronist leader, who had been president of the Chamber of Deputies. Jose Espejo, from the food union, was general secretary of the CGT from 1947 to 1953. Pedro Gomis, leader of the oil union, was a national deputy from 1952 to 1955.

William Patricio Kelly was the only man at arms to take from the group. At the time of the coup, he was the main leader of the Nationalist Liberation Alliance. A very controversial character, but at that time he played an important role in the Peronist Resistance.

Cooke's description of each of them is interesting in a letter to Perón from Santiago de Chile.

Campora, Kelly and others according to Cooke's vision

On March 21, 1957, aware of the escape, Perón wrote to Cooke: “My dear friend, you can imagine the satisfaction I have had with your spectacular “piantada”. We really “jumped our caps” when we unusually received the information that you were safe in Magellan.”

On April 11, Cooke, from Santiago, sent to Manuel Araujo an extensive letter analyzing the political situation in the country and Peronism. They are striking, some considerations he makes about several people.

Cooke says: “The Socialist Party, now under the command of the nymph Moreau de Justo, criticizes the social economic and trade union policy of tyranny. Since it does not clarify what it is that it supports of the Liberating Revolution, I suppose that it is administrative policy, which ignites the fervors of the People's House, with its consequent awarding of professors, positions and rented interventions for the members”

Then he talks about the “components of the Rio Galleguense mission”, that is, the group of escapees. Of Jorge Antonio it only says “he will travel there as announced”.

He continues to say: “Campora, when he was arrested, made a promise to God that he would never act in politics again. Throughout his captivity he insisted on that attitude. How he spends his day praying, I don't think it violates his oath. At all times he stated that he was not a man of struggle, so it cannot be of great use. I clarify that he always reiterated his friendship and appreciation for you, so my assessments apply only to your fighting possibilities.”

“Gomis is an excellent guy, but let me advise him not to keep him around because he is obsessed, and of those who think about everything and every opportunity. Since the poor man has the most certain instinct of inopportunity (...) one is willing to keep him at a distance because it drives the calmer out of his mind. It's brave. I could provide great services in connection with the oil people in our country...”

“Espejo, inside the prison he behaved with dignity, and had, before, the gesture of leaving the embassy where he was a refugee to organize the strike in November 1955. Among working people, their prestige increased a lot in the last year.”

“I have treated Kelly very thoroughly, with whom I have shared 16 months of captivity. He knows how to organize and will be very useful to us. The alliancists have a special mentality, which Kelly knows well, it is useless to want to mix them with the other people in the movement. In Buenos Aires, many elements that respond to Kelly are released (...) they will be able to carry out sabotage missions and at the decisive moment collaborate forcefully. Kelly could be very useful to you, and assign him to any mission no matter how dangerous it is.”

In the jargon of the seventies, a character who entered the path of violence by political convictions was called “iron”, but over time, the taste for action surpassed political reasoning. Guillermo Patricio Kelly is one of these cases, over the years he ended up being linked to right-wing gangs and intelligence services from other countries.

Cooke adds in his long letter: “Another matter. They announce the arrival of Damiano, who fills me with joy. In my presence they tortured him on June 10 to make him declare who the members of the Peronist Command were not able to take a word from him. He was released a couple of months ago and then went looking for him again but he managed to flee to Uruguay. An invaluable element.” The curious thing about this mention of Cooke is that Manuel Damiano, who in 1955 was General Secretary of the Press Union and designated by Cooke as a hero of the Resistance, in 1973 will participate in the clashes on June 20 in Ezeiza on the side of the defenders of the box, from there considered a “target to be executed” by the organization Montoneros.

Of the six escapees from Rio Gallegos, the only one who remained in detention in Chile, awaiting extradition to Argentina, was Guillermo Patricio Kelly. But, on September 28, 1957, he escaped from the penitentiary of Santiago with the help of the poet Blanca Luz Brum, a woman who has a novelistic life, whose history subjugates.

Aldo Duzdevich is the author of Saved by Francisco and La Lealtad-Los montoneros who stayed with Perón.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies