Behind each of the twenty-three people killed by the bomb in the Federal Police dining room are family, friends and colleagues who still today they still mourn them, like Gloria Paulik, who learned of the death of her father, Sergeant Juan Paulik, when she was ten years old and was the third of her five children, born and raised in a family in Villa Ballester, in Greater Buenos Aires, where she never had enough money.

Or like Juan Carlos Blanco, son of the cashier in the dining room, who had given him his full name, a sign of how long the boy had waited after four female daughters. Juan Carlos was eleven years old when he found out at his home in Ciudadela about a news in which he still doesn't believe at all: “I hope every day for him to come home,” he says.

There were other times: the wife took care of the house and the husband provided the money, at least in the Paulik and Blanco families. The deaths caused pain and also sudden, unexpected, financial difficulties to the point that, for example, Paulik's widow and her five children had to leave the house they rented.

There were five women among the victims of the Vietnamese bomb that destroyed the casino of the Federal Security Superintendence on July 2, 1976, in the downtown Buenos Aires.

One of them was the only person who did not belong to the police, the only civilian victim: Josefina Melucci de Cepeda, 42, who worked at the state-owned company Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscal, and went to lunch with her friend, Sergeant Maria Olga Pérez de Bravo, who also died.

“Fina, the document is ready; come and get it,” Maria Olga had warned her, early in the morning. It was the passport of a neighbor of Josefina; she lived in an English-style house in Villa Urquiza with her husband, Antonio Cepeda, and their three children: Alejandra and Carolina, aged eleven and Gabriel, age ten.

Always cheerful and willing, Josefina had asked her police friend for the document of a neighbor's son.

Carolina Cepeda last saw her mother that Friday in the middle of the morning, when the Line B subway stopped at Uruguay Station and the girl went down with her dad, who was taking her to the doctor. It was the last kiss she gave her and that would accompany her, like a treasure, throughout her life.

The mother continued to travel one more stop, to Carlos Pellegrini station; she worked for a couple of hours at the YPF headquarters and went out to lunch with her friend; on the way, she entered a store and bought a cover, forced by the intense cold of that winter noon.

“The Montoneros bomb destroyed my life,” said Carolina Cepeda, who was just five years old: “She forced me to wear a mask to hide the pain of losing my mother in such an absurd way. Do you know what it is like when Mother's Day comes and that, while your companions are drawing pictures for their mothers, you know that the only thing you will be able to do that day is bring a flower to the cemetery? And that you have to put on your best face because people don't have to put up with your pain every day either?”

Her older sister, Alejandra, was eleven years old. “My mother was a sun; she had arrived from Spain at the age of nine; she was a cheerful woman, always very helpful to her neighbors and her co-workers, at YPF, where she fulfilled administrative duties,” he recalled.

Fina's husband, Antonio, had to file the family dream of expanding the rubber store they owned on the border between the neighborhoods of Villa Urquiza and Belgrano R, for which they had already bought a larger property because, logically, he had to take care of the three children, who were very young.

“Dad died three years ago; he was an exemplary father and we miss him very much. He always wanted justice,” Alejandra said.

“I think the two sisters never wanted to have children so they wouldn't suffer what we suffered after the bomb,” Carolina said. “The same thing happened to our brother, Gabriel, who was ten years old and was also very affected,” Alejandra added.

Josefina Melucci de Cepeda died instantly from a deep wound at the base of her neck and her body was removed the next day by her husband.

Although most of the diners used to be low-ranking police officers, employees from shops and companies in the area also went to the Casino of the Superintendence of Federal Security, on Moreno Street at 1400. For example, de Suixtil, who was on the corner and manufactured suits, jackets, shirts and ties, and where non-commissioned officers and officers could open a current account with a single signature. Also from YPF, ESSO and some banks, such as El Nación.

María Olga Pérez de Bravo, the hostess of that fatal meal, was 43 years old, and was admitted to the Churruca “in a coma, having to undergo surgery on her skull to remove a large metal shard embedded in the heart of the brain tissue, which caused esphalation (gangrenation) of it”, according to the doctor Richard Lotito. In addition, it “had multiple holes of three to four millimeters in diameter” in the right leg, nose and forehead. She held out eight days until she died and her body was also removed by her husband, Alfredo Bravo.

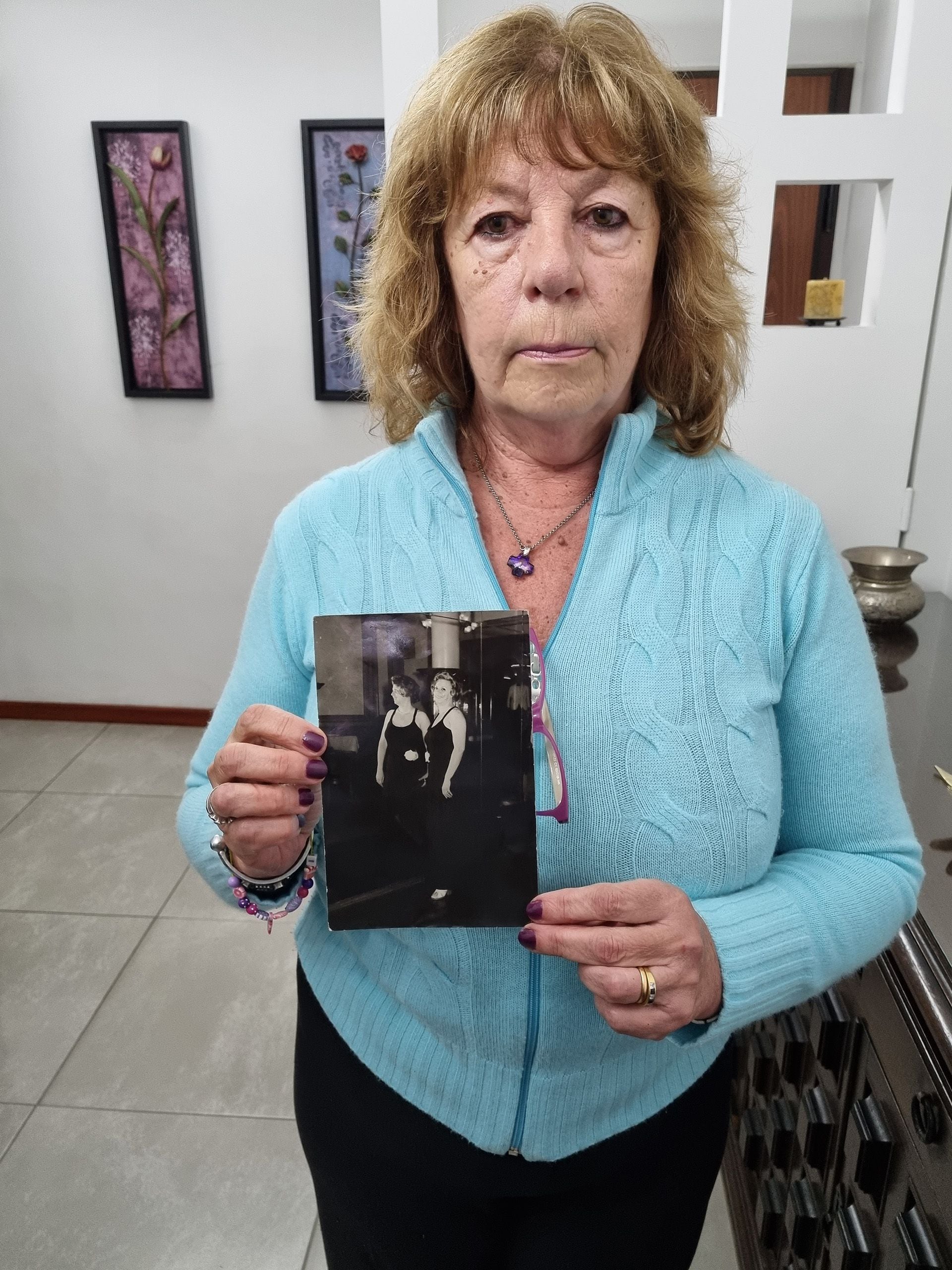

The third female fatality was Corporal Elba Ida Gazpio, who was twelve days away from turning forty-seven. Her twenty-three-year-old daughter, Liliana Tejedo, was an agent and was eating with her, but she got up ten minutes before the explosion to give her chair to a friend of her mother's, Sergeant Maria Esther Pérez Cantos.

A fortuitous event that saved his life. “I saw that Maria Esther was standing because she couldn't find a place; there was an incredible crowd in the dining room because it was the beginning of the month and we had collected our salary,” Liliana said.

“María Esther, I finished eating, sit here,” he said, rising from the table, with his wallet in his hand.

“No, if you guys are chatting.

“I'm already late for the office.

Agent Liliana Tejedo walked less than a hundred meters, climbed into the elevator and, when she reached her desk, on the first floor of the Central Department of the Federal Police, where she was performing administrative duties, a deputy commissar came in very agitated.

- Did you hear the explosion? she asked Liliana and her companions.

“No, here, in the building? she replied, recalling that there had been bomb threats in the Central Department.

“No, it looks like it was at the Federal Security Casino.

“That's when my drama started,” Liliana Tejedo recalled.

It's just that mother and daughter were very close, probably because Liliana's father had abandoned them when she, who was an only child, was seven years old. “With a salary that we barely survived, my mom got us both ahead. She worked on the first floor of Federal Security, in the Department of Records and Reports; in administrative tasks, she didn't even carry weapons,” he said.

“Then I found out,” he added, “that the bomb had been placed right behind me, on another table. Maria Esther sat in my place, my mom was right across the street. Therefore, their bodies were destroyed; in my mother's case, the identification process took almost ten hours and it was only at midnight that they confirmed that she too had died.”

“We were very close,” he recalled. I never went back to the dining room and spent years unable to get through the door. I did not go to the wake, which was held the next day, on Saturday, July 3, in the roofed courtyard of the Infantry Guard, in the Central Police Department. I couldn't even go to the tribute organized by his office mates. They gave me leave and I'll be back in fifteen or twenty days. I worked there until 1980, when my son was born and I asked to leave.”

“It's a topic that keeps making me very nervous; it makes me sick; since we set the day of the interview, I'm sad. In more than forty-five years, it's the first time I've talked to someone I don't know,” said Liliana Tejedo on the verge of tears.

He added that “a lot of people who know me don't know how she died because I always say she died in an accident. I don't think I could stand it if someone answered me, for example: 'The military did horrible things. ' My mother had nothing to do with it; she was a poor worker, who fulfilled administrative duties and didn't even carry weapons! He barely survived on his salary, but with that salary he got us through when my dad abandoned us. She died just as she was finishing the separation process.”

It was his uncle, Deputy Commissioner Horacio González, who handled all the paperwork related to the identification and removal of Elba Gazpio's body, which took almost ten hours because he was completely mutilated, while Liliana was comforted by her husband and grandmother.

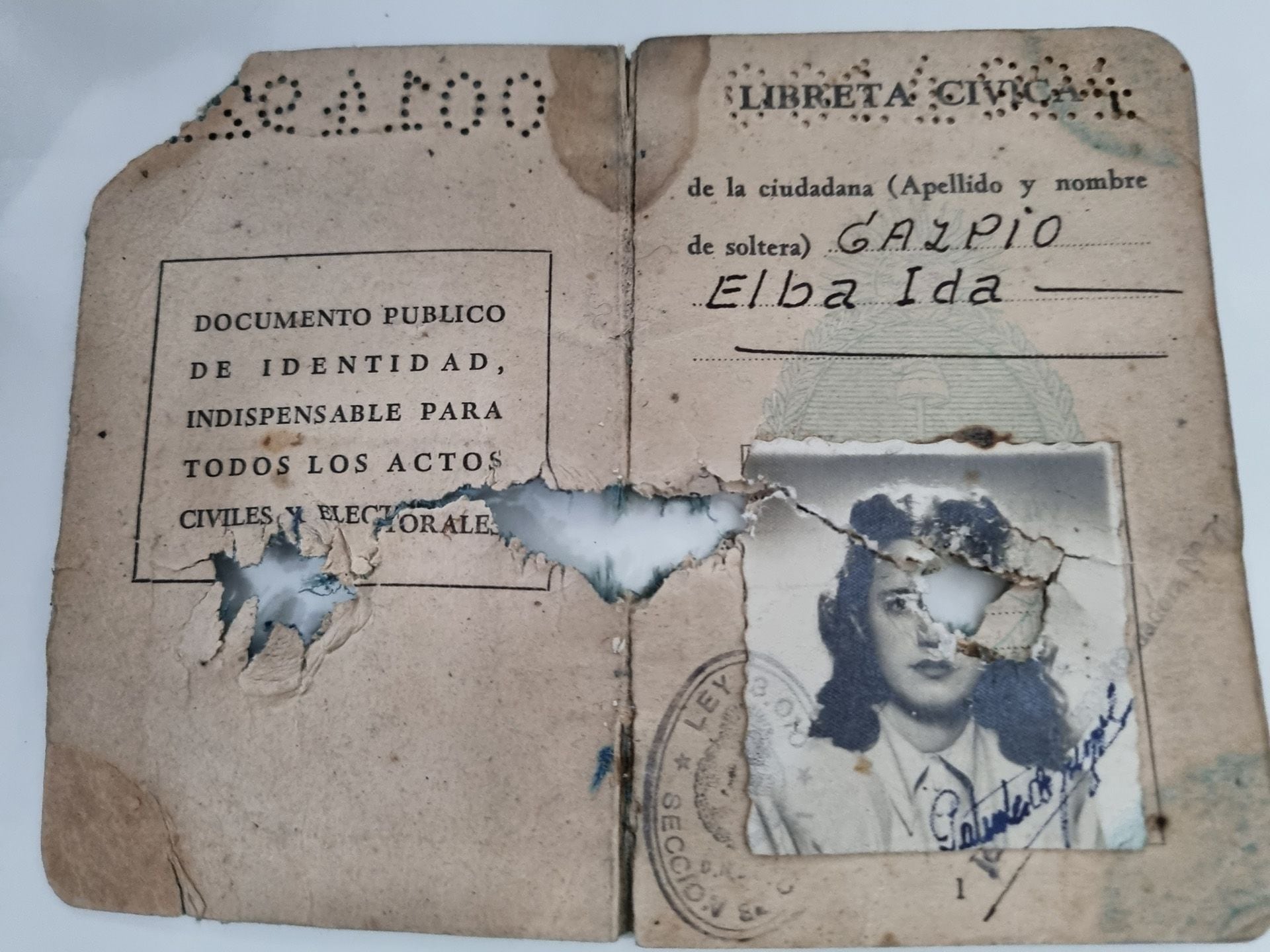

“There was,” said Tejedo, “a failure in the control of entry to Federal Security. It had a huge gate, but always a leaf of the gate was open. On the sidewalk a policeman asked you where you were going and, right after the entrance, there was the surveillance desk, but, if they already knew you, they rarely made you open your wallet. In fact, my mom died with her wallet. Eventually, my uncle gave me his identity card and an agenda that he had in his wallet: they were pierced by the steel balls of the Vietnamese bomb.”

Elba Gazpio's body was completely mutilated: she was decapitated, with multiple fractures in almost all the bones of her skull and face, and loss of brain mass. Dr. Luis Ginesin explained that, in addition, he had multiple injuries and fractures in his legs, the “traumatic amputation” of the right arm, and wounds and fractures on his left arm, from whose hand they managed to remove two rings.

Her friend, Sergeant Maria Esther Pérez Cantos, 49, was the fourth woman on the list of dead; her body was removed by her daughter, Maria Susana Burgos Pérez. His head was also separated from his body; “multiple skull fractures, exposed and closed, with loss of brain mass; type AB (intermediate) burns in the malar and right mandibular region; wounds to the right leg, and scoriations and bruises in different parts of the body,” according to Dr. Jorge Luis Russo.

The last female victim was Agent Alicia Lunati. His body was charred from the navel down, as were his hands, and he had intermediate burns on his face and scalp, and scoring and bruising all over the place. His father, Pedro Lunati, removed the body; he also received two white metal rings, one with a colorless shiny stone, and a hundred pesos that his daughter carried in her pocket.

The bodies were so damaged by the characteristics of the Vietnamese bomb used by Montoneros, one of the two most powerful guerrilla groups of the 70s, of Peronist origin. It did not contain only trotyl but also posts or steel balls, which, once the device was detonated, turned into a blast that pierced everything it could find, from tables, chairs and walls to the diners themselves.

One hundred and ten people were injured, several with very serious consequences due to the mutilation caused by the shock wave, while eating the good, hearty and cheap dishes in the dining room.

Montoneros claimed that he sought to preferentially eliminate the senior staff of the Federal Police, as the “center of gravity” of the illegal repression of the dictatorship, but of the twenty-three dead only two were officers and of very low ranking. Seven of the fatalities were not even doing police duties: the diner, the cashier, a waiter, a nurse, a fireman, a retired non-commissioned officer who was doing his job as a bread delivery man and the YPF employee.

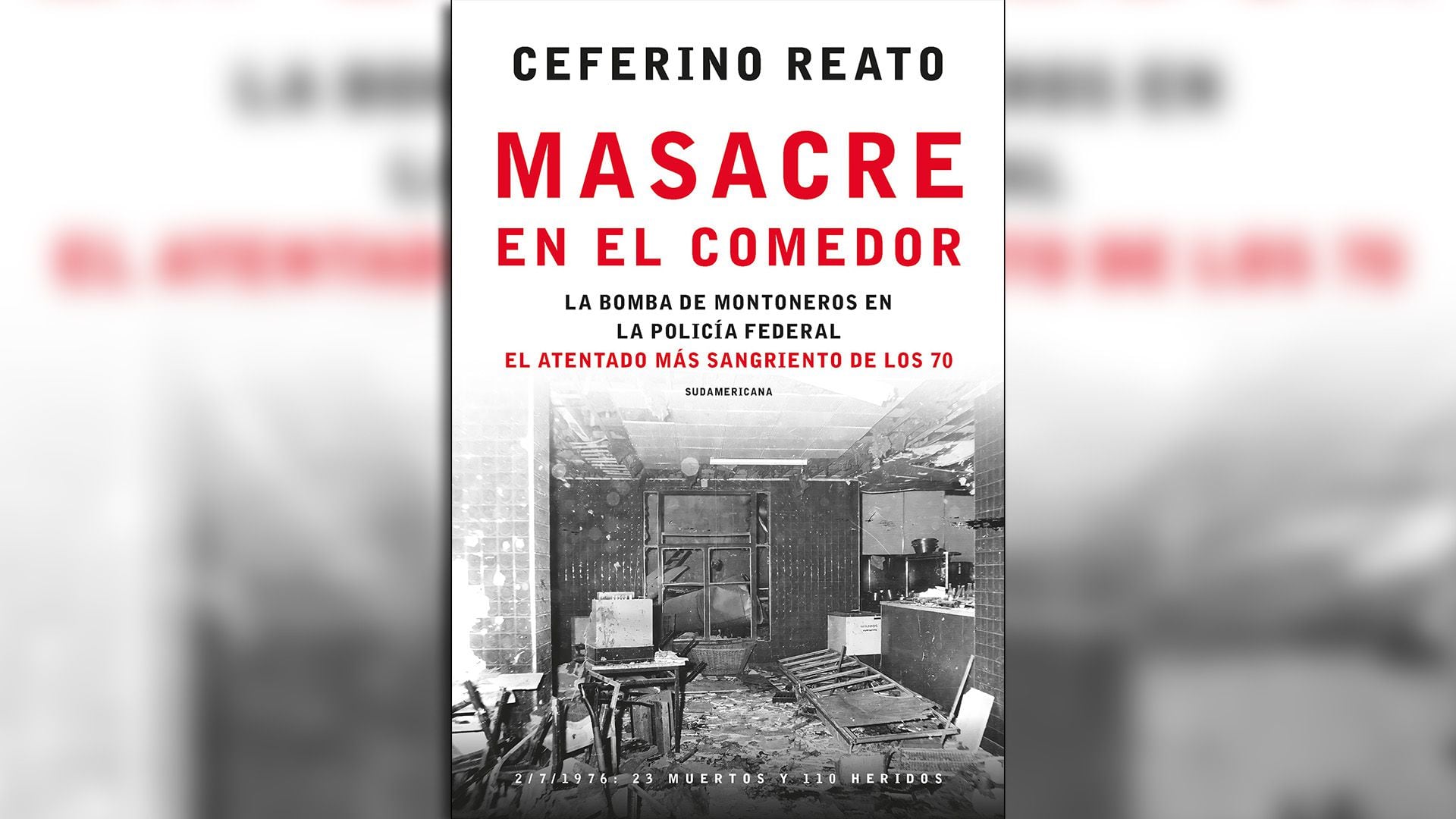

It was the bloodiest attack of the 1970s, but also in the history of the country until July 18, 1994, when a car bomb destroyed AMIA and left eighty-five fatalities. It killed more than the terrorist attack on the Israeli embassy of 1992, thirty years ago. And it would have killed even more if Montoneros had achieved its original purpose of tearing down the entire building.

Beyond our borders, it continues to be the biggest attack on a police unit in the world. No other police officer was attacked like that. Despite all this, the Justice never investigated him, neither during the dictatorship nor in democracy, and until Massacre in the dining room, no journalist or historian had written anything on this subject.

*Journalist and writer, taken from Massacre in the Dining Room.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies