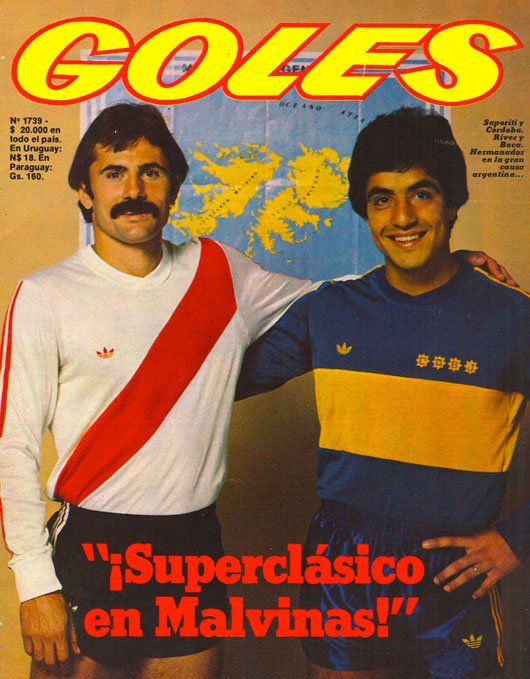

It's almost customary for him. Although he follows Boca from the United States, where he settled in the 80s, before each Superclassic someone draws his attention by reminding him of the extraordinary play he made before Maradona left Fillol crawling on the mud of the Bombonera. Diego's exquisite definition was engraved in everyone's retinas, but if the play is rewound, Carlos Córdoba has nothing to envy to Diez. Exclusively with Infobae, a few days before the Boca-River that will be played at Monumental, the former footballer xeneize shared his memories.

On a personal level, the 3-0 to River in La Bombonera was not the one who scored him the most, since he was pleased to score a double in Núñez to the longtime rival. And that was a left-back! He talked about everything: the coexistence in Boca with Maradona, which he was pleased to lead in the World Cup Rapid Football that took place in late 1994 in Mexico, his involvement in the remembered players' strike in 1984 that forced him into exile and a return to Argentine football to be Oscar Ruggeri's field assistant in Independiente, at the time in which Kun Aguero appeared.

At just 17 years old, Juan Carlos Lorenzo made him debut in the First of Boca Juniors. He had had football teachers acting as parents such as Nano Gandulla, Ernesto Grillo and Vito Damiano in the lower ones, while Carlos Román was in charge of the last baking in the Third (now called Reserva). Trobbiani, Mouzo, Tarantini, Gareca and Ruggeri were other names that were forged next to them. It was a time of glory for the club, which won the Libertadores and became world champion in 78. When referring to his beginnings, it was inevitable for him to draw a parallel with the young people of today's squad: “Playing in Boca at that age opens a lot of doors to temptations. They kept us short, they put us on track and held us because they knew we could be wrong at any time. Pancho Sá, Loco Gatti, Pernía, Mario Zanabria, Chapa Suñé, Toti Veglio, Russian Ribolzi, Chino Benitez were incredible guys who taught us how to behave.”

Córdoba married young and had a girl shortly after. A costume anecdote tells what the handling was like by the referents: “When I got my money, I bought a Fiat 600. I was happy to train and when I got off they called me Sá and Suñé and asked me where I got it from. I had bought it from another colleague, which I'm not going to name, ha. Since I still didn't have a house and I was renting, they called the previous owner of the car and had him return my money. They told Monkey Perotti to pick me up every day to go to training and I would collaborate with gasoline. Until I had a house, I couldn't buy my car. Those are examples that are not seen today. And keep your mouth quiet, eh. Not a word was answered.”

It was not the only anecdote he had with a vehicle through. When he was already represented by Guillermo Cóppola, he told the famous agent that he wanted to give his father a car. “Are you crazy? For what? Your old man won't be mad if you don't buy it for him. Tell him that tomorrow we are going to visit him in Merlo and that he prepares a roast,” Guillote retraced. Today he thanked that gesture: “I was right. My old man wanted the least was a car. That's why I think that nowadays kids buy things for them, that's all.”

On the case of Agustín Almendra, a youth with great potential who had an interview with the coach and some teammates in recent weeks, he said: “It hurts what happened . When you start in Boca, friends appear from all over the place, more than you had in your entire life. And some kids don't have that family support that makes them see things as they are. The family is the greatest support that the football player has. I spent three years in Primera to buy my car, today the kids who didn't make their debut already have one. There are entrepreneurs and agents who help you, but others who are not good. Those who don't have a front finger, make them believe stars without them being. The kids don't realize that it was hard for them to get there and it's very easy to disappear.” And he exemplified: “Maybe they advise them 'if you get the points Roman, Bermudez or Chiche Sonora, you answer them'. But in reality, if they tell you something they rest assured that it is because they passed it and lived. In Argentina you open a door and 10 guys who want your job fall. In two seconds you disappear.”

HIS FRATERNAL BOND WITH DIEGO MARADONA

Cacho Córdoba faced Argentinos' Maradona, then shared a locker room with him in Boca and in late '94, when Diego was suspended by FIFA, he led him in a World Cup Rapid Football that took place in Mexico. “You have to listen to Groncho, who is clear about it with this little game,” Diez told the rest of the Argentine squad in reference to the DT who lived in the United States and had been professional in indoor football.

“As a person, as a guy, he was barbaric with us. He was the first to make jokes and screw you. And when you saw him train, a different, an out of place. It was in a different orbit than the rest. I don't think another player looks like him. Messi today is our flag, the best in the world without a doubt. But I don't compare it to Diego. The one who knew Diego, was lucky enough to see him play and share with him, he knows that there will be no one like it”, takes the words from the deepest part of his being.

The Boca del Metropolitano 81 played great football but was also crowned by group union. And Maradona was a standard-bearer in every way. The anecdote about the air rifle proves this: “One night we were in the games room of the La Candela concentration, where there wasn't much to do. Some of them played ping pong and others sat in some armchairs. Suddenly they started shooting at us. We didn't know what was going on and there was nothing to be seen outside. Diego appeared and said 'che, they are throwing us out'. After a while, again. Pin, pun! We didn't realize it was him until we saw he was sweaty. He hid in the trees, threw us down and came running to play the one who was frightened. It was a lot of fun and damn. And at the time of playing, he was transformed, a born winner, he had nothing else on his mind. He was handsome, he played even injured, as he did the first 10 or 12 games until Marzolini stopped him.”

On April 10, 1981 Boca gave lecture to River at La Bombonera. Maradona spread Fillol for the 3-0 of a rout that Miguel Brindisi had opened with his double. Before Diego's final stiletto, Córdoba cut a breakthrough from River and traced a route from his left back to become a right wing and center to the penalty spot for Pelusa. If Negro Enrique ever boasted his intervention in the Goal of the Century against the English, Cacho could calmly inflate his chest without irony because of the player he put together before Diego's best goal in a Superclassic.

“A lot of guys don't know my name, but when they see the play they realize who I am. With the simplicity that Diego defined, no one remembers what happened before. It was a perfect match for us. Made by Diego, on Boca's court, against River... I didn't prepare it, it came out and I was lucky that they didn't cut me in half on the way. Because Passarella had thrown a lot of kicks at Diego that day. If he threw it at me, maybe I didn't have Diego's vision to jump him and he would have killed me. I got out of the operation without anesthesia.”

The time and paths of one and the other caused contact to be lost. On top of that, several players who were represented by Guillermo Cóppola in Boca gave the agent the go-ahead to go to Italy to manage Maradona's race: “Come on, if you're going to win 2.20 here with us and you may not even get it”. There was a phone call with former Argentinos Juniors Pedro Magallanes as an interlocutor and the reunion in the World Cup Rapid, but little else. His infinite memory is still latent for him.

Diego's death created a huge vacuum in his chest: “It hurt me and it hurts a lot. I find it hard to believe he's not here. All Argentines have to be proud of him. When you talk about your problems... His personal life is his personal life. Thanks to Diego they met us all over the world, whoever likes it. It hurts to know everything that happened. One was not around to evaluate everything, but you see pictures and I think no one liked how it ended, especially those of us who were next to him and knew him well. For me it will always be the guy I knew, the one I saw acting and doing things for other people. We can argue days and days, but for me he will be the guy with a big heart who killed himself for what he did, for Argentina and for everyone.”

FROM HIS OTHER GREAT SUPERCLASSIC TO THE STRIKE IN BOCA AND EXILE TO THE UNITED STATES

“I was wrong, ha.” This is how Cacho Córdoba responds when asked about the 1982 River-Boca at the Monumental in which he scored two goals. It was for the Interzonal of the National Tournament. That afternoon, Alfredo Di Stéfano's team started winning by Jorge Alberto Tevez's goal, but Xeneize turned the story around thanks to Ruggeri, Gareca (two) and the protagonist of this story, who finished the third and fourth, in the rebound of a penalty kick that Alberto Montes had covered him.

He said about his other golden page: “The one who is a Boca fan knows what a goal against River is worth. You don't forget it anymore in your life. I liked to attack and that day Zanabria gave me a barbaric pass, I had eyes everywhere. And that penalty was one of the last ones I kicked. I was already grabbing them, if anyone approached me I would say 'where are you going? '. He was the only one who saved me, eight or ten that I threw away.”

His history in the penalties had started in the lower ones, when in a visiting Superclassic the Pelado Grillo, who didn't talk much, shouted “Córdoba, hit him”. A teammate was the one who used to charge them, but that day one had already missed one due to weak shooting and the coach pointed to Cacho. “I put the ball in there and thought about taking the goalkeeper's head off. I kicked hard, I didn't think of one end or the other”, is the phrase that gives credit to the film archives of his executions on YouTube.

If he was a captain and reference in Boca at the age of 25, Córdoba had to leave through the back door. The 1984 squad went without being paid for nine months and, without answers from then-President Domingo Corigliano, decided to launch a strike that would later be extended to all Argentine football. Through the football players' guild, those involved demanded freedom of action, knowing that it would be difficult for them to reintegrate into the medium. “They had wanted me from Europe, but I wanted to stay in Boca all my life. They can tell me what they want, but if we didn't make that stoppage and that board of directors left, Boca might end up as Racing with Lalín,” he said.

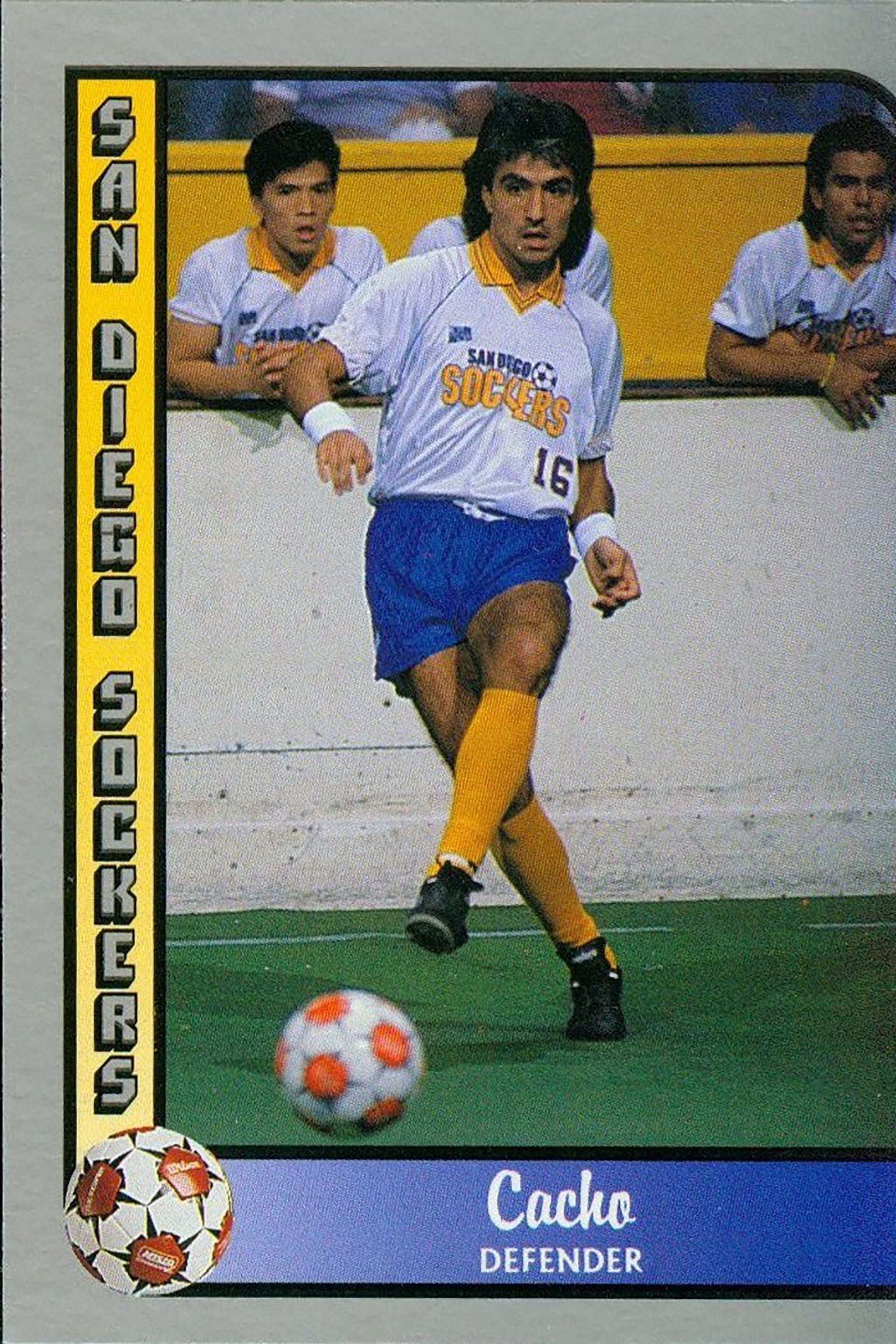

Cacho Córdoba joined a blacklist for which he could not get a club in Argentina. He was even banned along with others to sign on a team in Lincoln, Buenos Aires province, which had called him up. His only alternative was to sign for a league that was not a member of FIFA, since Julio Humberto Grondona, a man who was already strong in the international federation, had it signed up. A representative based in Los Angeles had contacted him during a Boca tour of California and opened the doors for him to join the Major Indoor Soccer League: Fast 6v6 football and unlimited changes. By way of testing, he defended the Tampa Bay Rowdies jersey.

He had a stormy return to Argentina. José Varacka, who had already wanted to take him to Deportivo Español, was the architect of his signing for Huracán. About 15 bars of the Globo went to look for Córdoba at his home to convince him to sign, since it was the condition of the new coach that he was part of the team. In Parque Patricios they orchestrated a ruse to prevent Grondona from realizing that Cacho would be in Argentine football again and his arrival took shape. It did not last long. He received the repudiation of many people for having been the architect of the strike and there was a campaign against him. Profe Jorge Castelli took him six months to play in Unión de Santa Fe, but he already knew that his final destination was the United States, where even in that almost amateur football he paid more than in Argentina.

So it was that it was reconverted. From the smell of grass — and occasionally mud — of 11 courts to the synthetic smell of the small military courts at Kansas City Comets, San Diego Sockers and Milwaukee Wave over the next five years. He retired prematurely from football, but continued to be tied to him in Wisconsin.

INDEPENDENT, RUGGERI AND THE KUN AGÜERO

With football that had excelled since the years when Pelé had played for the New York Cosmos in the 1970s, Cordoba saw in detail its progress and spread throughout the United States. He began working with youth in local, neighborhood clubs, which were not yet fully organized. The formation of the MLS in 1996, as a result of the explosion that generated the World Cup two years earlier, was key to its development as a coach. After a decade and a half in the country of basketball and baseball, he was called by his former teammate Oscar Ruggeri to try his hand at Mexican football, much more professionalized than American football.

El Cabezón had already made his debut with the DT diver in San Lorenzo and was contacted by Chivas de Guadalajara for the 2001/2002 season. He then passed through Tecos, where Córdoba also accompanied him, before landing in an Independiente who with him tried to put out the fire of a bad campaign during the 2003 Clausura. “It was very good to return to Argentina after so long. It became difficult because my family was used to the United States, but we had a great time. I was an assistant to Oscar and led a Reservation that did very well. We found boys like Lorefice, Matheu, Abraham and there was Aguero,” recalls Cacho.

With Ruggeri and Córdoba on the bench in the last six matches of Clausura 03, Rojo had been unlucky, although the Apertura of that year started undefeated (victories against Estudiantes, Banfield and Olimpo, plus draws against Newell's, River, Quilmes and Arsenal). However, a home defeat against Colón de Santa Fe on the eighth date led them to the resignation: “You realize when you are well or not in a place. We weren't what the fans wanted. Oscar had a palate more of Bilardo than for Independiente. There was no communion with people.”

On several occasions and publicly, Ruggeri confessed that over time he realized that he had not prepared enough to be a technician. His former assistant contradicted him loudly: “You are wrong. What happens is that he did not direct anymore, he sees everything that the kids do today and associates it with that time. When you stand in front of a group, you have to show knowledge of what you are doing because the player knows, feels it and perceives it. Oscar had a clear message about how he wanted to play. I was fully prepared. He thinks that today because he looks at how he works now, where there are many more tools. I completely disagree when he says that he was not ready to lead.”

He no longer wanted to work outside the United States and therefore refused to return to Mexico with Ruggeri to take charge of America. De Avellaneda took the memory of a jewel called Sergio Leonel Agüero: “When we arrived at the club they had already told us about him. I had something else, it was different, solid, strong. I told Oscar and we took him to the First when Milito, Franco, Rolfi Montenegro, Pusineri and Guiñazú were there. The Kun went and played as if nothing happened. Outside the court he was a boy, but inside he was a man. As soon as Oscar saw him, he said 'that's it'. The day he made his debut, he was on the bench in a jacket that fit like a coat, his feet couldn't be seen how big he was. We had fun watching him play because he was so brave. When they came to him, he squatted down, put his ass back and turned with ease... It's very nice that it was what it was. And the important thing is that he is in good health now, he has already passed it, lived it, made his career and left his mark on every team he played.”

Carlos Cacho Córdoba is director of a youth branch of Orlando City in the United States. He leads the male U16 and the female U15. He always watches Boca's matches with his wife (who is more fanatical than he is) and, when he travels to Argentina, he takes a walk around La Bombonera.

On the evolution of American football, he said: “Everything has changed a lot since MLS. Before there were four or five top international players, the rest were from local universities. When the Colombian Valderrama came, he could play with one eye and one leg if he wanted to. Today it is one of the strongest leagues in the world at the economic level and they no longer come to retire. Young players are bought narrowly to sell them for a lot.”

In any case, he argued why there are shortcomings within the training structure of the United States: “The player here does not have the professionalism of the South American. Here they work an hour and a half, three or four times a week, hopefully because the boys are going to study. In Argentina it's the other way around. It's hard to create that passion and dedication. In Argentina football can be a salvation, here they are already saved when they leave a university because they have a degree with which they will earn a lot of money. Boys aged 15, 16 or 17 don't have the mentality of South Americans. When you explain everything you have to do to the one who wants to be a professional player here, it's all over.”

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies