Everything comes back, and so does Seinfeld. Now that the legendary series can be remastered on Netflix, although with some bumps that seem too wrong today, it becomes clear again that life sometimes looks quite like a Seinfeld joke that repeats itself until someone arrives with their finger raised and cancels it. Or to thousands of repetitions of ironies about nothing itself, which go from causing us grace to being canceled by violent ones. It could be a gag from the show, but then again, it's life.

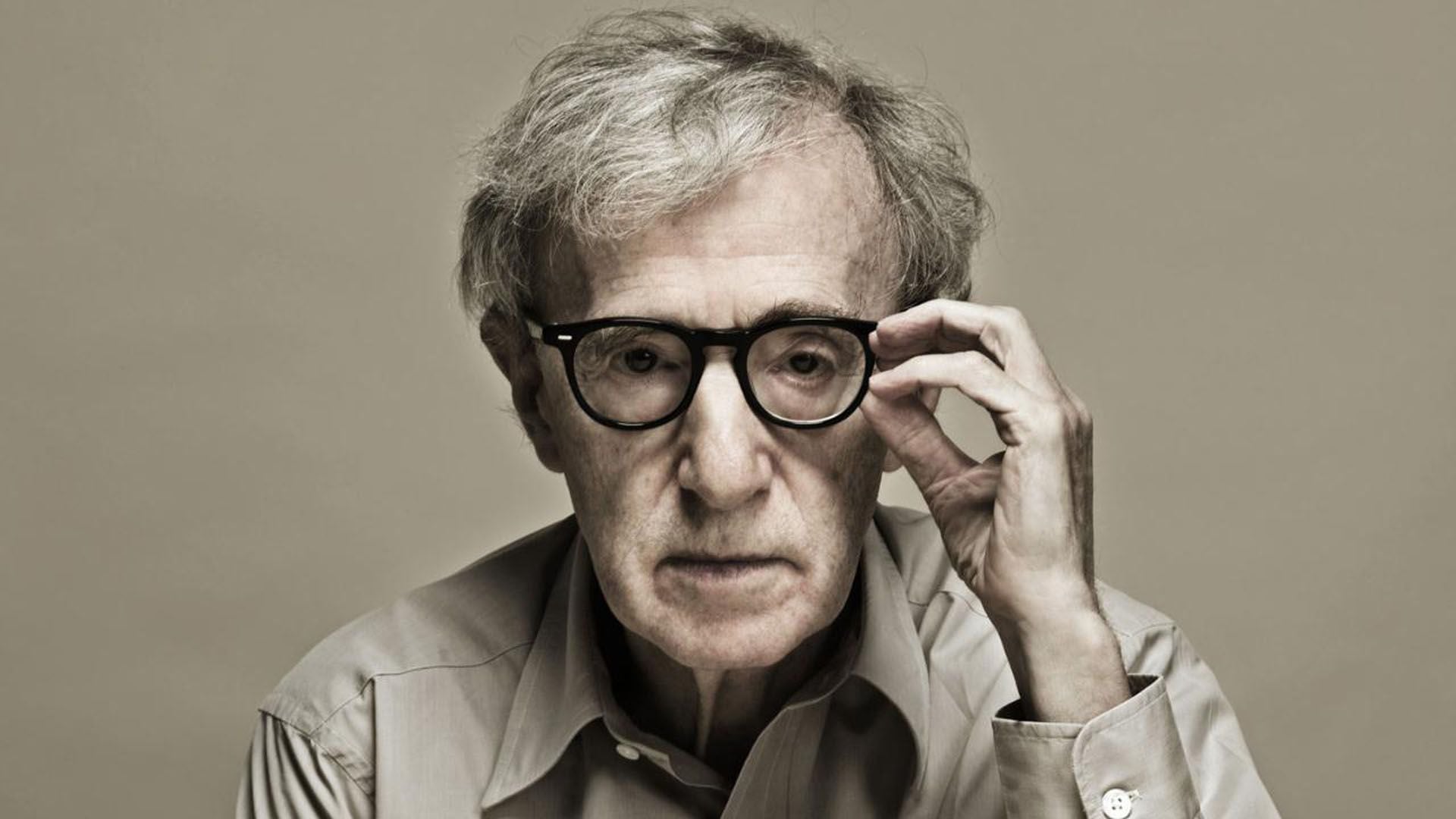

I got tired of talking about cancellations when a few months ago I read in a very good interview with Marcelo Stiletano with Woody Allen that the director — the guy who turned their backs on overnight stars who would never have been if they didn't act in his films, the man who best portrayed female neurosis in the cinema, the one who he was interested in portraying it when no one was doing it, but that he had to make a pilgrimage with his memoirs from one publisher to another as an outcast after the story of the alleged abuse against his daughter that everyone knew was refloated and nobody seemed to care for decades — he said that he did not feel at all a victim of that culture that exposes, excludes, professionally and personally boycotts and ostracizes those who engage in unacceptable behavior in a society that claims to be perfect in ways, but is generally far from being so in fact.

“I'm not a victim of anything because I'm still working,” said the genius who invented Annie Hall, and convinced me that if others cry cancellation it's because they're just that: crybabies. We hear all the time that today the tyranny of political correctness is imposed, and also the ridiculous phrase that “nothing can be said anymore” is imposed. But the purest truth is that nothing could ever be said anywhere in the world if one was not willing to tolerate the answers, which today networks amplify exponentially.

It is also true that, as never before, today we can all say anything, with a scope that does not distinguish levels of virulence: the good, the bad, the interesting and the plain and plain hatred, are just a click away. On the networks, yes, but also in the media, which, again, as never before, today are quite similar to the experience of a blogger or a youtuber who thinks, talks and writes in solitude, without much prior debate, without the old cover or guideline meetings; now everything is immediate, and mistakes or wrongdoings — for those who dare to commit them — will be part of tomorrow's indignation. Food. And the wheel is still spinning anyway. Even Woody isn't canceled.

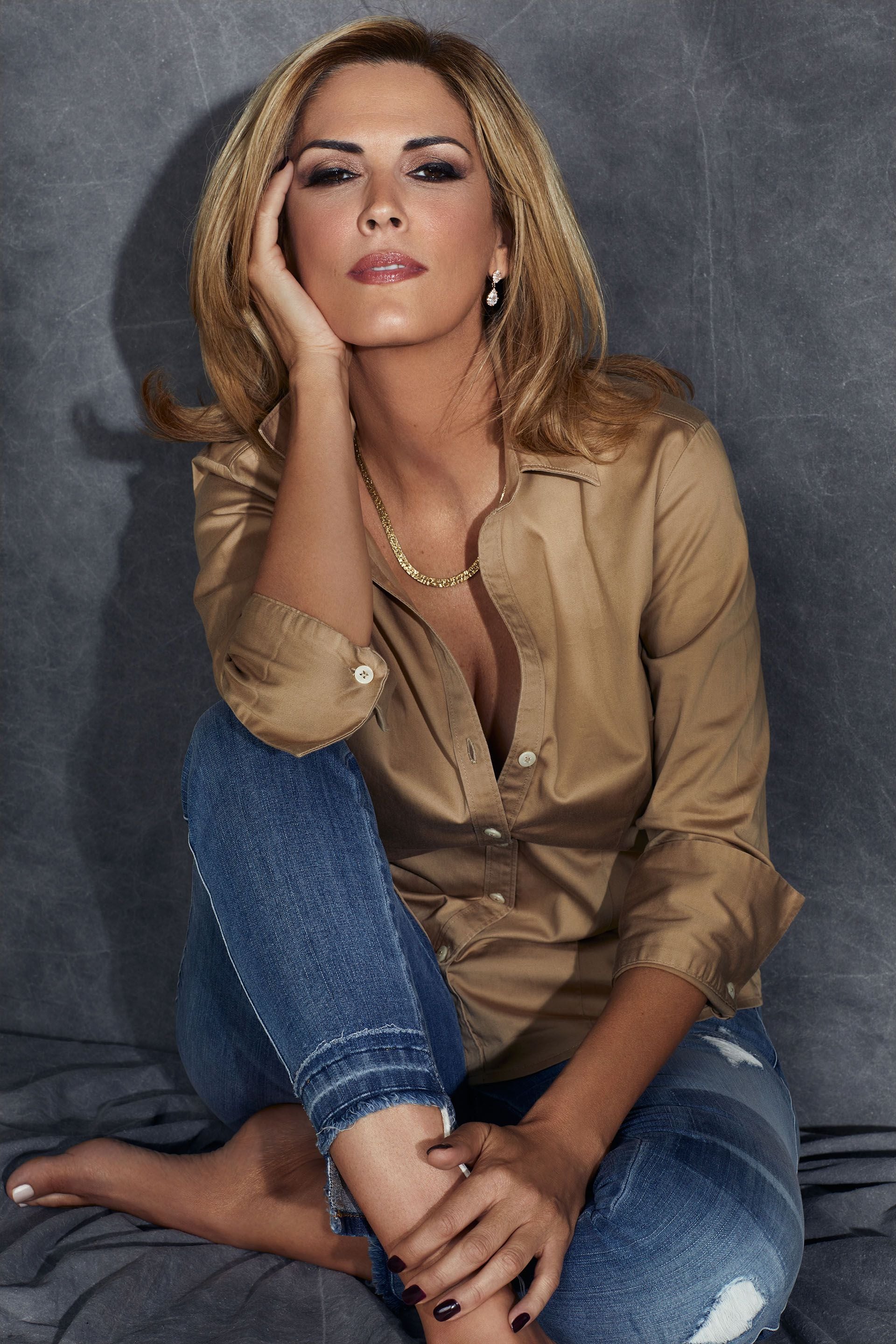

But let's go back to Seinfeld. Or rather that cool character we've all been or want to be, Elaine Benes. Well, last week I was Elaine and I had to be one on a rather particular day. I met the most handsome man in the world, I was crazy lucky that he noticed me —blessed, yeah—, and in the middle of a night that seemed perfect he quoted in a non-ironic way what for a while now Argentina has become the new nemesis of feminism, Viviana Canosa. It was after, on the subject of #8M, the driver sent us to bathe and waxing, as was done in the eighties. And just when it is used again as then to say that it is better to “be feminine”, as if such a dichotomy existed. I confess that last week I was angry, but now, as I write it, it makes me laugh.

How is it possible for someone to make so much noise with such poor and worn arguments? Pages and pages to answer him, hours of air; me right now, writing this column; the most handsome man in the world, quoting her convinced that he was repeating something reasonable. The answer is not very difficult: just watch his program. I have been doing it for a while, and I must say that it makes me as angry as it entertains me. Once I'm in front of the screen it's impossible for me to stop looking at it.

Canosa is television, beautiful — every day more, and she bathes! —, unleashed; in a world where everyone is measured before speaking, she is not afraid of the consequences. On the contrary, he found a niche there, and that is that it was almost served. Again, if even Woody Allen — someone singled out for the worst crime, pedophilia — hasn't really felt canceled, why would it happen to her? The monster that justifies some proclaiming themselves as the brave voice of freedom certainly does not exist. No one really has the power to cancel us, in any case, they will change channels or terminate our contract. And Canosa knows that's not going to happen to him; conversely, his show improves with criticism.

But why does the cancelling monster sometimes seem so real if it doesn't exist? Why does it seem to give pasture to that other, reprehensible monster that ends up in a horrible escrache like the one he did last Friday against the editor of Genre de Clarín, Mariana Iglesias, as a return of kindness for a critical column that that newspaper put up, and even in a free one full of lies against that of TN, Marina Abiuso, who never even referred to her and fulfills her role with exemplary restraint while being harassed daily by thousands of anonymous people whom these escraches stimulate?

Won't we be unwittingly contributing to feeding him? This is another question that we have to ask ourselves: if at every act, in every march, in every space, we sometimes seem to show only the voice of a uniformed feminism that speaks in exclusive-inclusive, prioritizes us unindebted but fails to condemn Alperovich, and underlines all genres with a theoretical framework about how to live, say, do and even feel, the Canosa phenomenon will continue to grow by its own weight and that cropped photo of feminisms — which, we know, are, we are, much more than that — will do the rest very easily.

Again, I consume your program, it entertains me. So far there's no problem. But to defame journalists with first names, surnames and photos from prime time is a practice worthy of what Canosa herself often criticizes, and that crosses a limit. I do not think, however, that anything merits that it is not on the air, because for all this there is, in any case, justice. Forgive me, but I also don't understand those who accuse her of the appalling death of the little boy who took chlorine dioxide in Neuquén. Was it irresponsible? It is possible, but the responsibility for that child's life was not hers, as is not Robert Pattison's if a child dies trying to imitate Batman.

And yes, I understand, but I find it inappropriate that we continue to be outraged by what you think — and that particular way of twisting and mixing some facts to mark non-existent enemies — especially because that is what many people think. The most handsome man in the world, however, confessed to me that he also sees in Canosa a beautiful, brave (and bathed) woman. He told me that he agreed how she had stood her alone and made a path without claiming anything from the men or the “green handkerchiefs”. I told her that many of us can do that, but that the adventure of the women's movement is to bank together, that is what makes us strong and that she even achieved things for her, even if she didn't realize it: she works, she votes, she is a divorced mother who makes freedom her flag.

“You have a point in that,” he conceded, and asked me if I considered him a macho. I looked at him again, I thought I wouldn't care anyway, and I remembered the right man I was dating before, so worried about saying the euphemism just before I spoke, that he didn't usually care about anything else. I think now that this is the only thing — beyond unequivocal hate speech — that we should cancel all at once to get out of this rhetorical battle, which is exhausted in words, hurts many people, and moves away from the noble causes that we claim to pursue: the absurd idea that there is always the right thing and, even more so, that for everyone it means what is right himself.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs