He was born into a wealthy family in Rome and could have had a life full of luxury and carefree, but Elio De Angelis chose to sacrifice himself for his passion: motorsport, and reached the pinnacle of the sport. His manners of the Italian nobility, elegance and education, often contrasted with an atmosphere that was hostile to him. Although he never gave up, he was a great comrade and showed his skills as a pianist in the only Formula 1 drivers' strike. He was the winner and only death cut short the trajectory of the considered “last knight” of the Máxima. This is his story.

Elio came into the world on March 26, 1958 and inherited the passion for speed from his father Giulio, who owned a successful construction company and broke out of vice by running on boats in which he won several championships. But Elio leaned towards cars, after proving that he was also a good tennis player and an excellent skier.

At the age of 14 he started competing in karting and shared the track with another boy who years later also reached F1, the American Eddie Cheever, and at the age of 17 he was world runner-up behind the Belgian François Goldstein in the 100 cm3 category. In 1976 he was European champion and the following year he jumped directly into Italian Formula 3 and was champion aboard a Chevron and then at the wheel of a Ralt.

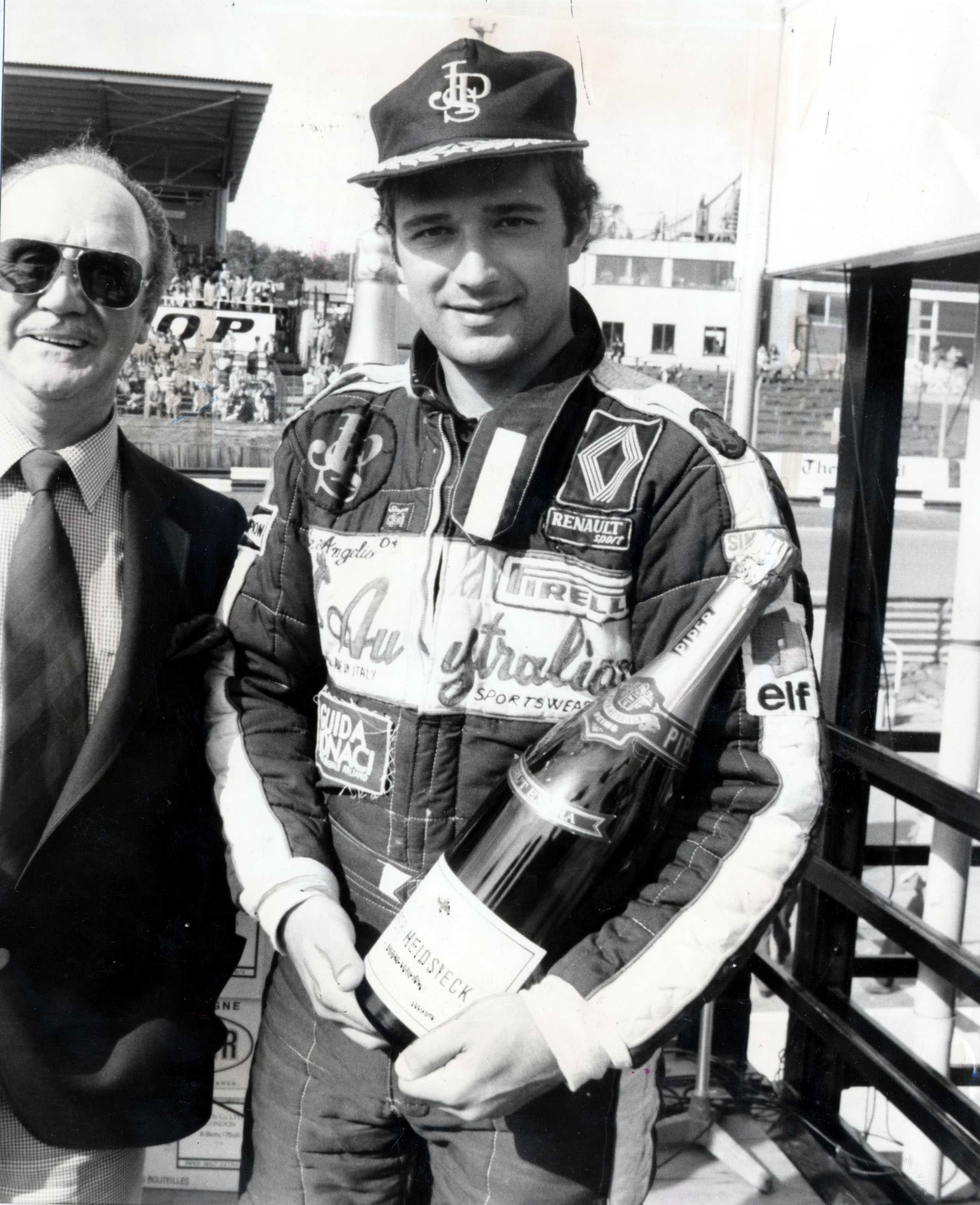

The atmosphere began to look at him with suspicion. The heir to the fortune of one of the richest families in Italy stood out in a world made for “tough” men like motorsport. “How was it possible?” , his detractors wondered. But there was something else and that response was that he was young, attractive, and with refined hands, who at social events aroused sighs among women every time he played the piano.

“No matter how much money you have, when you get in the car you're on your own,” he said. He was right. In sports, he made it clear that he had not come just because of the budgetary support of his father. He demonstrated his conditions and in 1977 one that caught his eye on him was Giancarlo Minardi, who in dialogue with Infobae reminds him: “I followed, as I have always done with all the riders, Elio from the first kart races and then in F3. I made all my experience available and with my team, Everest, we took him to fight and win the Italian F3″ championship.

“Elio was a great driver and only bad luck did not allow him to show all his talent, as a man he was an educated, sensitive, very intelligent and always cheerful boy,” adds Faenza's historic team-manager, who had Argentineans Miguel Ángel Guerra, Esteban Tuero and Gastón Mazzacane in his ranks. His team spent 20 years in F1 between 1985 and 2005.

But Minardi wasn't the only one. From Maranello they also saw him pasta and someone who had a clinical eye to “mark” talents was Enzo Ferrari. “I remember the day when after testing the F1 Ferrari in Fiorano, with an excellent result, despite a long negotiation with the 'Commendatore' Enzo Ferrari, he refused to sign a contract that would link him to Maranello. He could have replaced Gilles Villeneuve after his accident in Japan (1977),” Giancarlo revealed.

Miguel Ángel Guerra himself also met him, who in 1978 was his teammate in Minardi and in dialogue with this medium he tells what Elio was like: “When I arrived in Europe and I made my debut in European Formula 2 I had to be a teammate and we shared a room. He was an introverted kid, who spoke little, but he was an excellent person,” says the former F1 driver, multiple monopost champion in Argentina and who won the TC 2000 title in 1989. “He was a very good driver and we shared several races, he with the Dino Ferrari V6 engine and I with the BMW one. He had a pre-contract to race with Ferrari, and was going to be the first Italian, after Ignacio Giunti's fatal accident, to get into one of Enzo Ferrari's cars, who didn't want Italians on his team because of the criticism he received for Giunti's death. Elio's chance was cut short because he had an argument with a Ferrari engineer. Then I grabbed the Ferrari engine for the F2″. Then Guerra came to meet with Ferrari to ask him for a chance.

That year Elio also raced in Formula Aurora, which was an English category with disused F1 cars, in which Argentinian Ricardo Zunino won, who also reached the Máxima. In addition, Elio won the Monaco Formula 3 Grand Prix and the Shadow F1 team gave him a test in September. His records were good and he earned a place as a starting driver for 1979.

The big circus

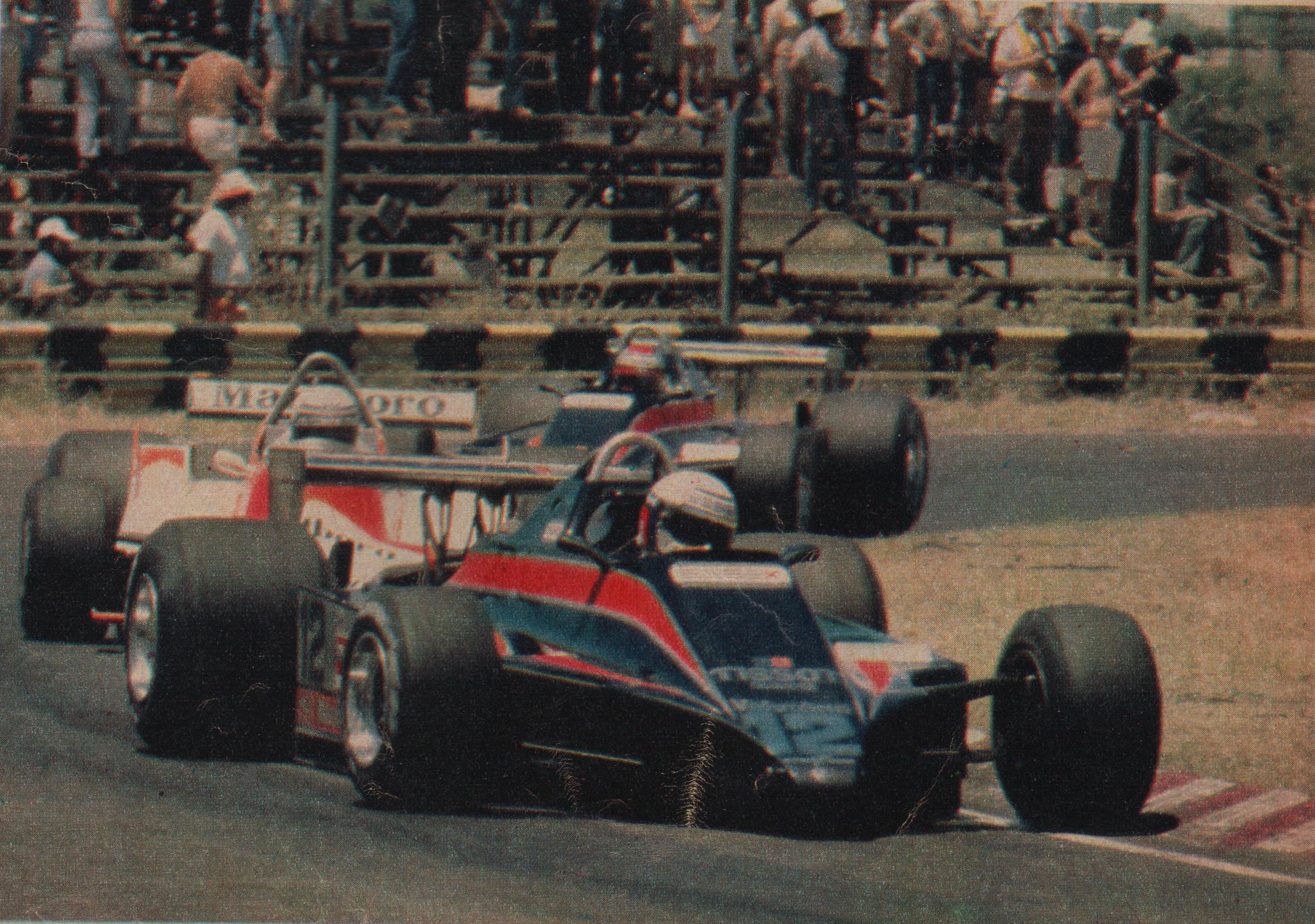

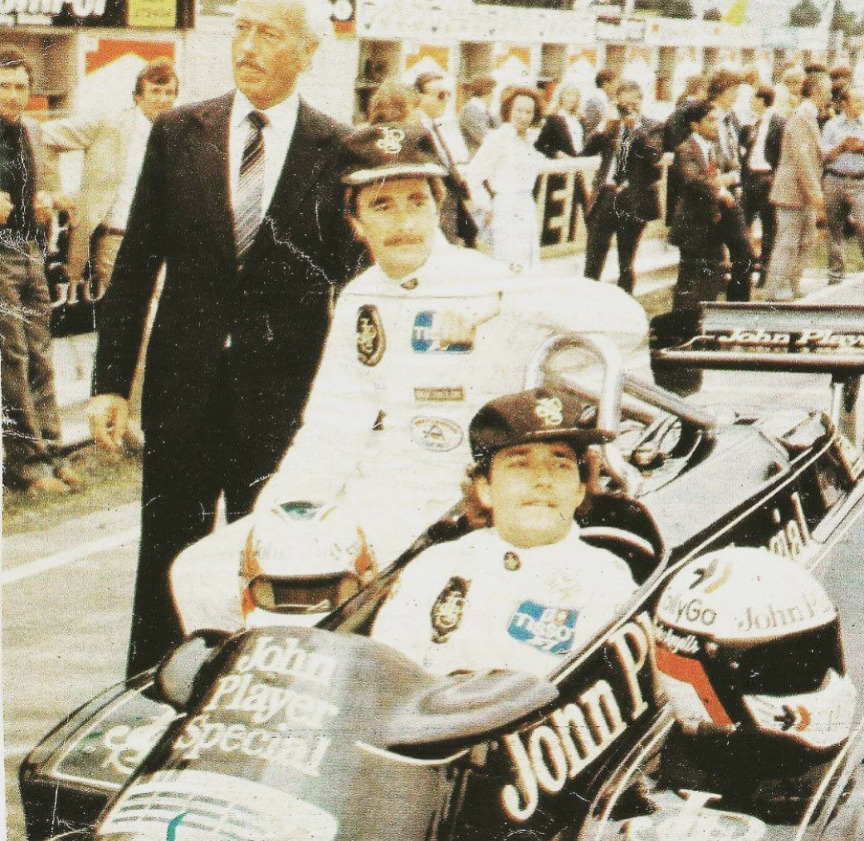

He made his F1 debut in Argentina and was seventh in an uncompetitive car. During the season he showed his condition and mettle, although sometimes he had excesses as in Belgium, where he took the Alfa Romeo of his compatriot, Bruno Giacomelli. But the team owners saw his potential, including Colin Chapman, owner of Lotus, who by 1980 had to look for a replacement for Carlos Reutemann, no less, who terminated his contract and moved on to Williams.

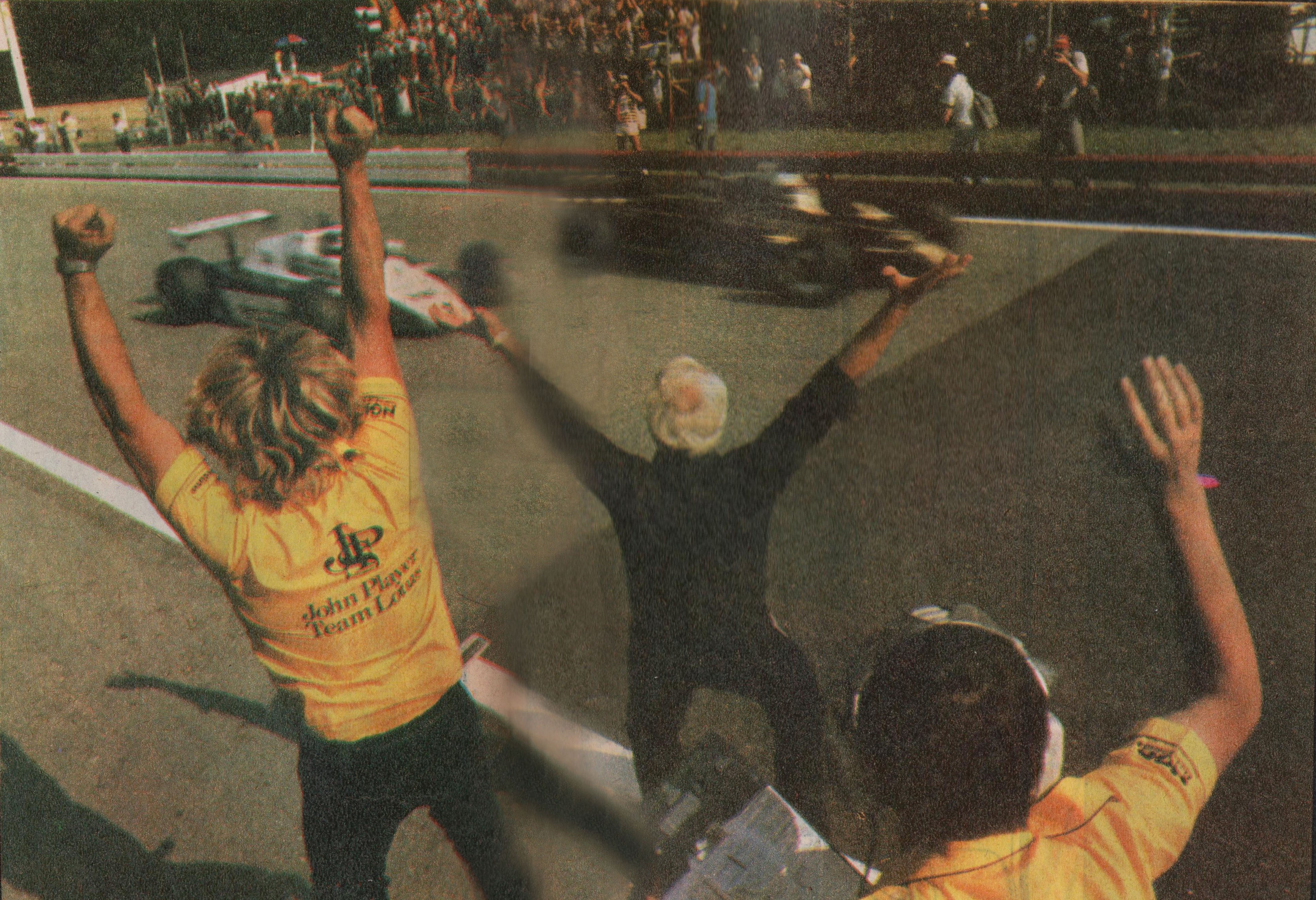

In Brazil he was second, but he could have been the youngest winner in history, since at that time he was 21 years old with a car that was not top of the line, such as the Lotus 81. Nigel Mansell's entry raised the bar, but in the first two years the Italian was better than the English and in that second season together, in 1982, Elio won his first F1 victory in Austria and with an agonizing definition for only 0.5 seconds against Keke Rosberg (Williams), in one of the tightest finals in history. “Rosberg was second and went on the inner side. I thought I had to do it at all costs: I blocked it in every way, it couldn't happen,” he acknowledged in a chat with Autosrint. That triumph ended the four-year drought for the team of Colin Chapman, its historic owner and the revolutionary car designer.

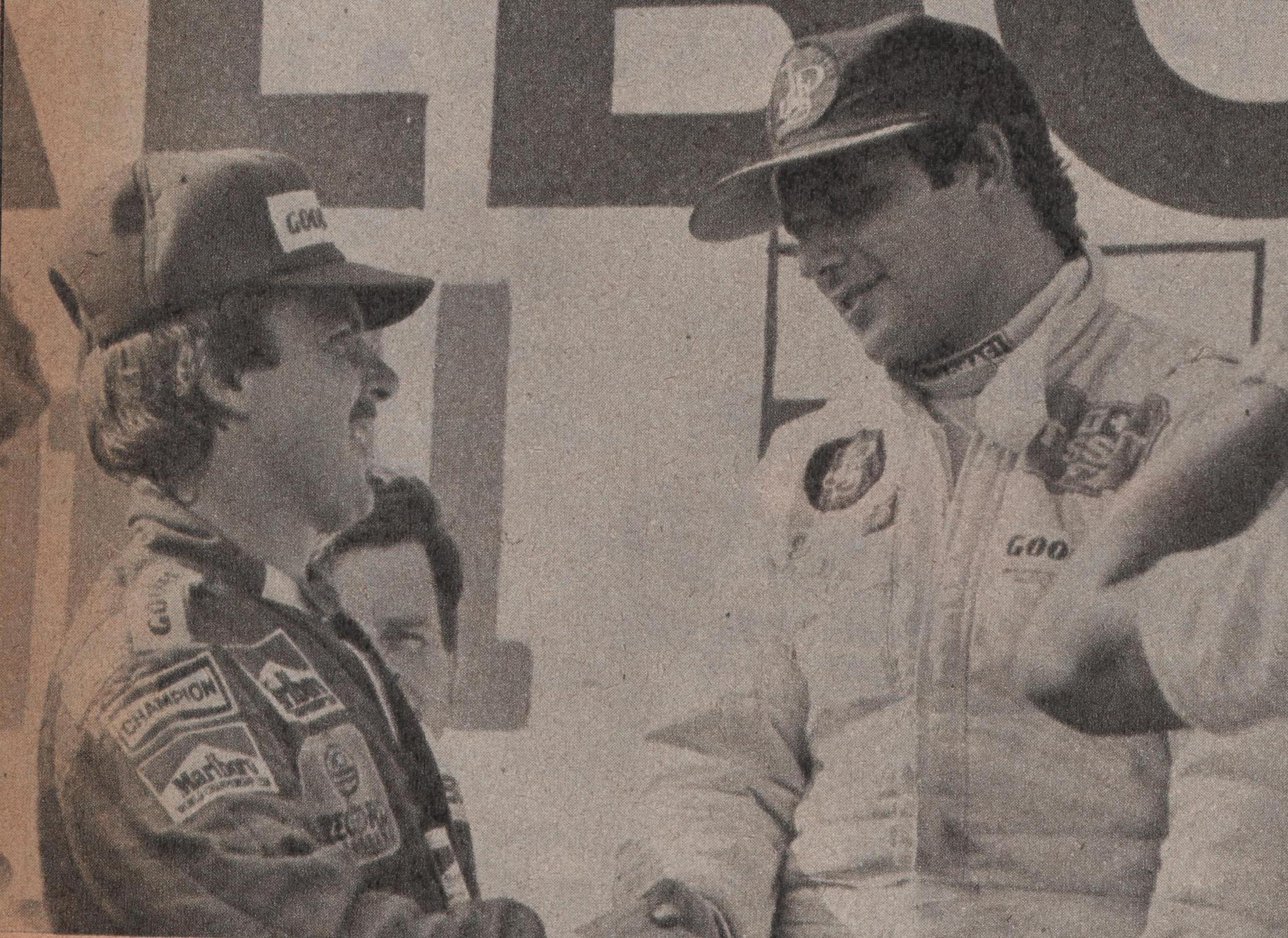

In January of that year, in the run-up to the South African race, the only Maxima pilots' strike was held led by Didier Pironi and Niki Lauda , demanding greater freedoms to negotiate contracts and to be able to testify in the media. To the extent of strength the runners mutinied in a hotel, slept on mattresses in a lounge and to spend time De Angelis played the piano for his colleagues.

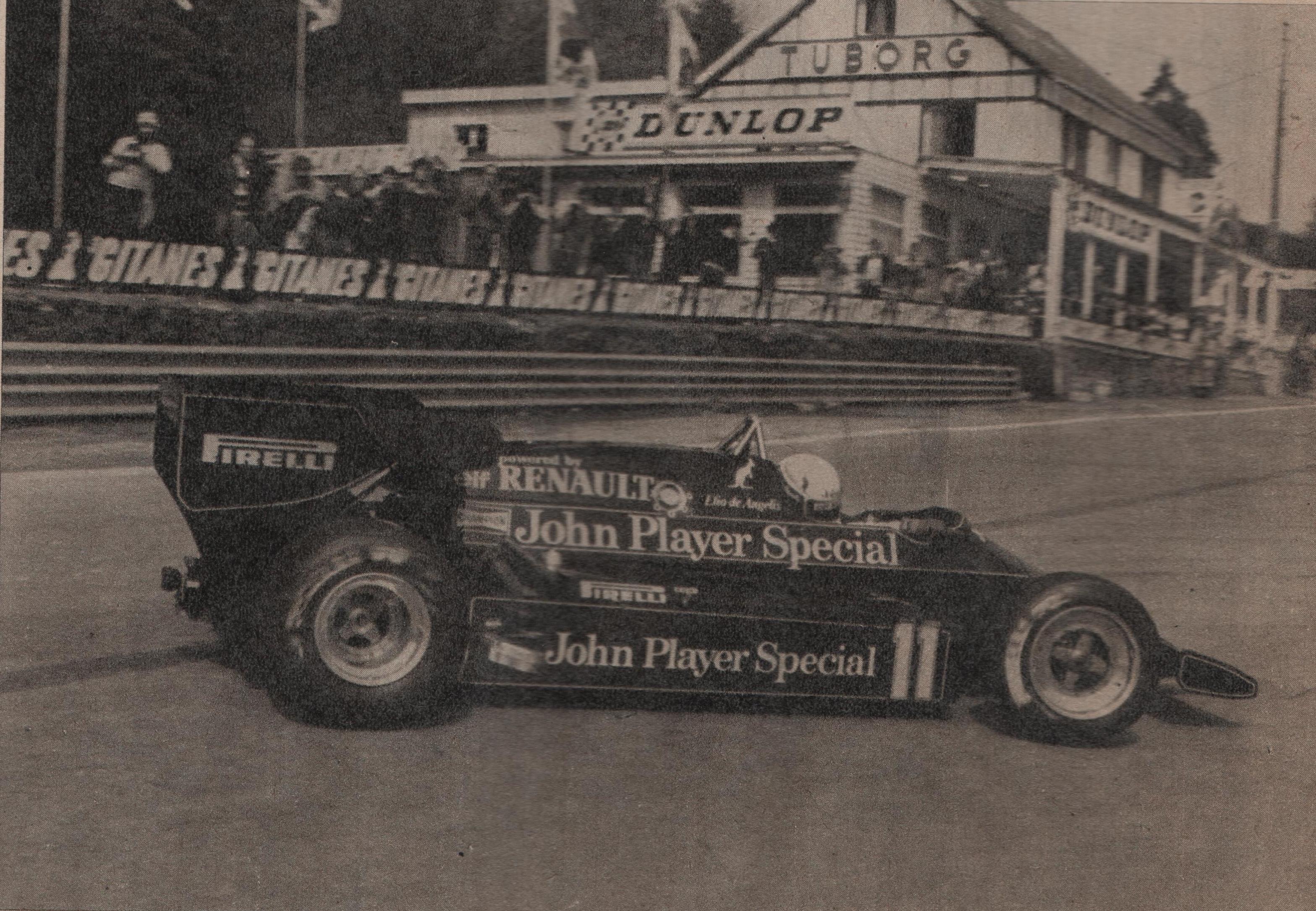

At that point he was also known by the nickname “The Black Prince” because he belonged to a rich family and because, until then, except in 1980, he always drove cars of that color. The entry of Renault's turbo engines did not bring good results to Lotus in 1983, but in 1984 the car responded and was the best of the rest behind the McLaren who with Niki Lauda and Alain Prost defined the championship. Elio was third and surpassed Ferrari racers, Williams and Brabham. The following year he repeated victory, in Imola, home of the San Marino GP, but it was after the exclusion of Prost. In that season he had as his partner Ayrton Senna, who won two wins and the Italian went to Brabham because he understood that the Brazilian received more attention from the team.

His death changed history

In 1986 he went on to drive the Brabham BT 55 of a radical design with a very low cross section, the work of the genius of Gordon Murray. That car was the embryo of the McLaren MP4/4, the most successful car in history (N. of the R: 15 wins out of 16 in 1988 at the start of the Prost vs. Senna). After Monaco on May 14, the team did a private tire test at the Paul Ricard Autodrome in France, where they lost their lives. “I met him in Monte Carlo on Sunday morning along the harbor and we consoled each other by his lack of qualification and that of my two riders in the race. It was the last time we spoke and Elio told me 'on Tuesday I'm going to Paul Ricard to try Brabham instead of Riccardo Patrese, who kindly left me his seat to see if I fit in this car'. Unfortunately, on Tuesday, a technical failure was fatal for Elio,” says Minardi.

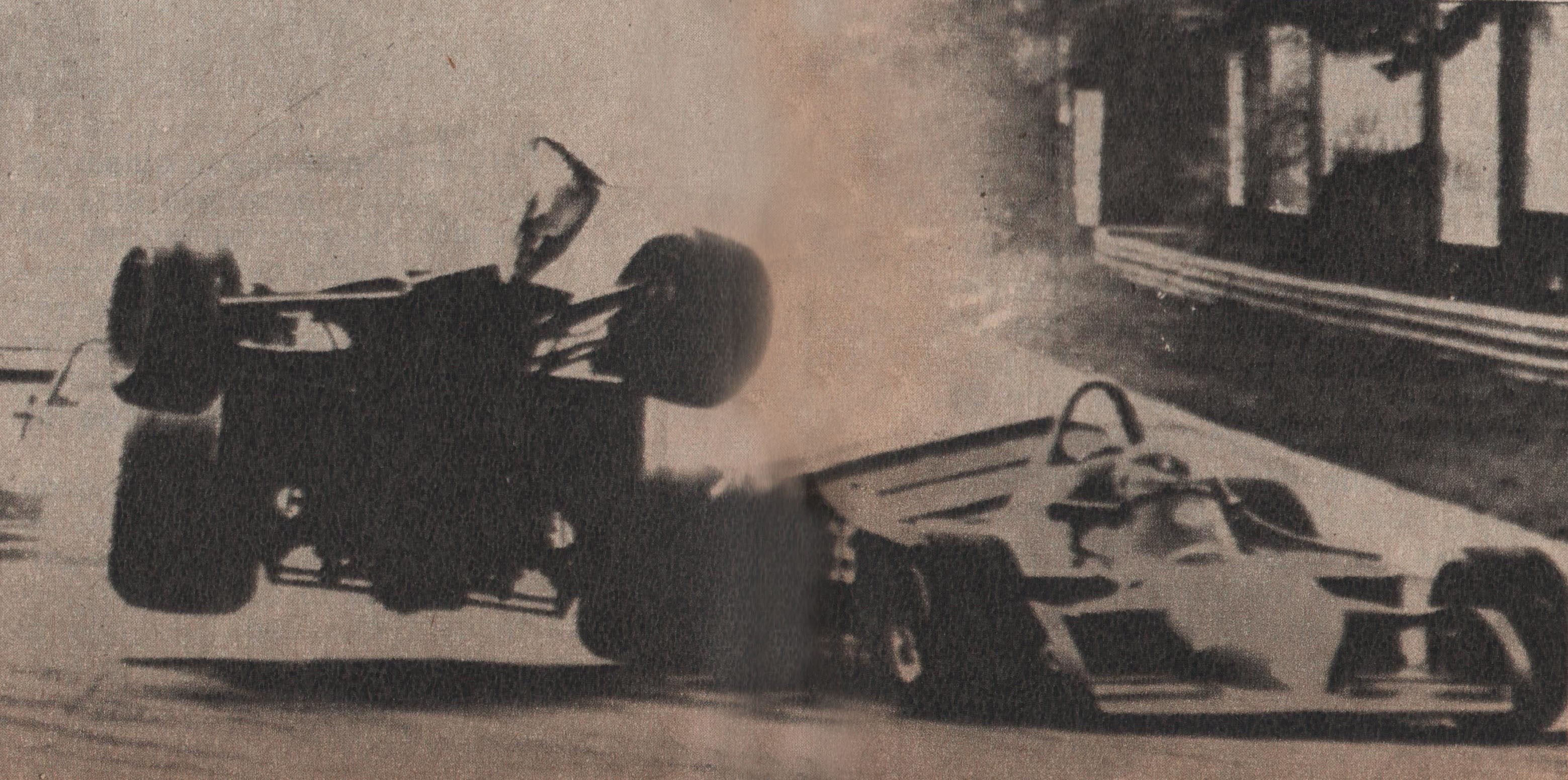

The fault indicated by Giancarlo was the breakage of the rear wing in the straight, which caused the car to lack aerodynamic load (attachments to make the car stick more to the asphalt) in the rear wheels, Elio lost control and rolled over three times. The car caught fire and Alan Jones, Nigel Mansell and Alain Prost tried to rescue it, but they didn't succeed. As they were unofficial tests, the safety device was very poor and even the mechanics arrived on foot and without fireproof clothing and shorts. The firefighters were delayed in arriving and managed to turn the Brabham around and get it out to De Angelis, but it took half an hour for the helicopter to appear. He only had a broken collarbone, minor burns to his back and various lumbar contusions, although due to the lack of attention in time and form, Elio died the next day, at the age of 28, suffocated by the smoke of his burning car.

From that moment on, the safety standards were changed for any F1 event on a racetrack: the presence of a helicopter and enough firefighters were mandatory to be close to the various sectors of the circuit. Also the rescuers, who in the case of De Angelis, if the fire had been extinguished soon, could have quickly turned the car around and pulled the pilot out before he inhaled the smoke. “Nowadays people get angry because the helicopter hasn't arrived for testing, whatever the reason, and you can't start without it. They need to see what happened that day. That way they won't get angry,” said designer John Barnard years later in dialogue with Motorsport.

Then it took eight years for the tragedy to invade F1 again and it was in 1994 with the losses of Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger. Until that time it was the longest period in history without deaths in the category, so the tragedy of De Angelis, served to improve safety and saved lives.

In that May 1986 summer in Europe was one month away, in which De Angelis could have rested on the best beaches if he had dedicated himself to his father's company, Giulio, and perhaps unleashed the vice as an amateur driver, paying as many rich people do in long-term races. But Elio was a professional, made it to F1 and was one of the best drivers of his time. And he left a reflection: “My father often asks me why I take the most complicated paths to reach my goals. I've never said it to his face, but it's because I discover that the pleasure is even greater that way.”

THE MEMORY OF ELIO DE ANGELIS

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs