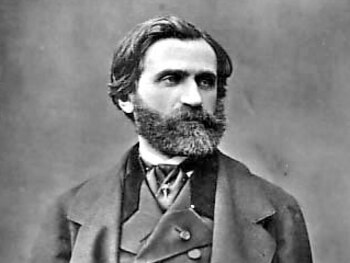

Giuseppe Verdi, one of the greatest musicians in history and a symbol of Italian unification, tried to give up music when he composed Nabuco, an opera that consecrated him as an artist and turned him into a liberal symbol.

During the Napoleonic campaign, the village of Le Roncole belonged to France after its annexation to the country. Born in 1813, Verdi was registered in the Civil Registry as a French citizen under the name Joseph Fortunin François. A few years later, thanks to his innate talent, the door to higher education was opened, which the humble innkeeper father could afford.

In a series of events after completing her studies and building a booming career around 1840, Verdi went through an important moment with the death of his wife and two children. At that time, Verdi was writing the second opera “Un giorno di regno”, which was released a few months after the incident, and it was a great failure and he did not know how his existence would continue.

Success was accompanied by good luck when businessman Bartolomeo Merelli handed over a script for a biblical drama written by Temistocle Solera about the texts of bAnsette Bourgeois and Francis Kornu. It was a story about Nebukonosol's conquest of Israel and violent tyranny.

Verdi arrived at his house when he received the script and said, “I threw the manuscript on the table with an almost violent gesture... It was opened when the book fell” and after a while I read the phrase that the whole of Italy would sing as a hymn: “Sullali Dorate” (“Fly Thoughts with Golden Wings”). That night he read the script not once, but three times. He was almost able to recite from memory.

Nabuco was a description of the stupidity of tyrants, limiting personal freedom. Following Austrian rule, the analogy with Italy was clear, and since Austrian domination was hiding under intense censorship, it permeated the artist's creations in one way or another to go beyond his message of independence.

However, the subtlety of the message in the biblical record was accepted by the Austrian censorship agency, and Nabucco premiered in Milan on March 9, 1842. We can imagine the writer's nerves through two years of intense work, details, rehearsals, proofs, etc., and there were many problems that night.

The premiere took place in La Scala in Milan, and the role of the crooked Abigail was sung by Guiseppina Strepponi, the most famous soprano at the time of becoming Verdi's wife for many years.

La Scala vibrated in a tense silence with the development of the play. In particular, the choir of Jewish slaves sang “Va pensiero” in the third act. Finally, the curtain fell and the audience broke out with applause. Nabucco was an opera that everyone expected, a song that aroused patriotic passions. The Israelites were Italy, a “beautiful and lost home.” On the walls of Milan, “Viva Verdi” sprouted and the secret cry of freedom, the dream of “risorgión”, and the desire for the unification of the Motherland hidden behind the bacronym Verdi (Victor Emanuel Re d'Italia) (King Victor Emmanuel of Italy).

The Austrians did not know how to react to this popular boiling. The dedication of a musician unknown until yesterday will be on everyone's lips from now on. For 65 nights, the theater applauded as the golden wing of freedom rose.

After Nabucco, Verdi did not have the same thing. Although he was a popular idol, the Austrians reviewed and closely observed his work. In 1843, the work “I Lombardy alla prima croasiata” was censored. Cardinal Gaetano Gaisruck demanded that part of the work be changed, and Verdi strongly opposed it. The composer was convinced that his reputation would guarantee his position. “It will not be done or done this way,” he said. The cardinal accepted the imposition, and the work was executed in its original form.

This is how a movement was formed around his person, representing the ideal of unity in a popular movement. He ignited works that explored political philosophy, such as Simon Boccanegra or Don Carlo, but arose to defend his beloved Giusepina from hypocritical gossip that criticized the soprano. When I was young, I lived an airy life and spent with my teacher. Years of living together without getting married (years later secretly). These bourgeois hypocrites are challenged by Verdi with La traviata (La perdida). Violetta Valery proves to be a true protagonist who is more dignified and loyal than members of the peaceful society that surrounds her. Verdi built a musical monument to his companion, as he once did for the freedom of Italy.

His political struggle was recognized by the same person with the name he hid. Victor Emanuele gave him the title of senator for life when he became monarch in 1874. It was to acknowledge their struggle and patriotic perseverance.However, disappointed in politics, the composer takes refuge in his hometown village.In this house now converted into a museum, tickets for the Roman Senate train are still precious. His world of arpeggios and chords was purer and more harmonious than dark political relations, so the composer never used it.

When he died, in 1901, people spontaneously gathered in front of his village and sang “bVa, pensiero”, which became an unofficial admirer of Italy, and finally said goodbye.

The history of the choir of the conquered people does not end here. After directing “Va, pensiero” on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the premiere, director Riccardo Muti and faced the audience's demand for encore, the premiere of Silvio Berlusconi told the attendees: “Today I am ashamed of what is happening in our country... This is how we kill the culture on which history is built.” Looking at the presidential box, he said: “I have been silent for many years. Now we have to understand this song”... And he invited the audience to sing all together this “Va, pensiero”, which is the freedom for the golden wings of his hometown “si bella e perduta”.

Keep reading: