Serapis has just published Essays on the Romantic Philosophy of Nature, an unpublished and fascinating anthology from different points of view, I will mention here some of them. Undoubtedly, the first reason for this book is found in the first pages, in its dedication “To Guillermo Colussi, genuine mentor and curator of this anthology...”, this review thus becomes —like the book itself— an event, a grateful tribute to such delicate intellectual work. The book also opens with a beautiful poem by Novalis that resonates with the expression “A secret voice” (Einem Geheimen Wort), which seems to allude to a fine thread that weaves together the selection of these texts, the voice of nature, Wort, word-voice, —that translation is already a topic—, and that in the first essay, “The symbolism of nature”, Schubert tells us about the “word of nature or, rather, of the god turned into nature”. A few lines later he adds: “For us, however, since that great confusion of languages, the very confusion of languages is, in a deeper sense, incomprehensible”. We cannot help but think that in this “great confusion of languages” is the mythical tower of babel, and in the god who professes “first was the word-verb”, the problem that translators face when faced with the concept of logos. Starting with Faust in his cabinet. A difficult text by Benjamin speaks of the double meaning of the word logos: as a “spiritual entity” and as “the linguistics in which it communicates”. However, after the fall of man into original sin, nature itself falls into a deep state of sadness; dumbness is its sign. Benjamin says:

“Where plants whisper will sound a lament [...] the sadness of nature makes it mute. In every grief or sadness, the greatest inclination is to be silent, and this is much more than a mere inability or lack of motivation to communicate.” “Language,” Benjamin concludes, “not only means communication of the communicable, but also constitutes the symbol of the uncommunicable.”

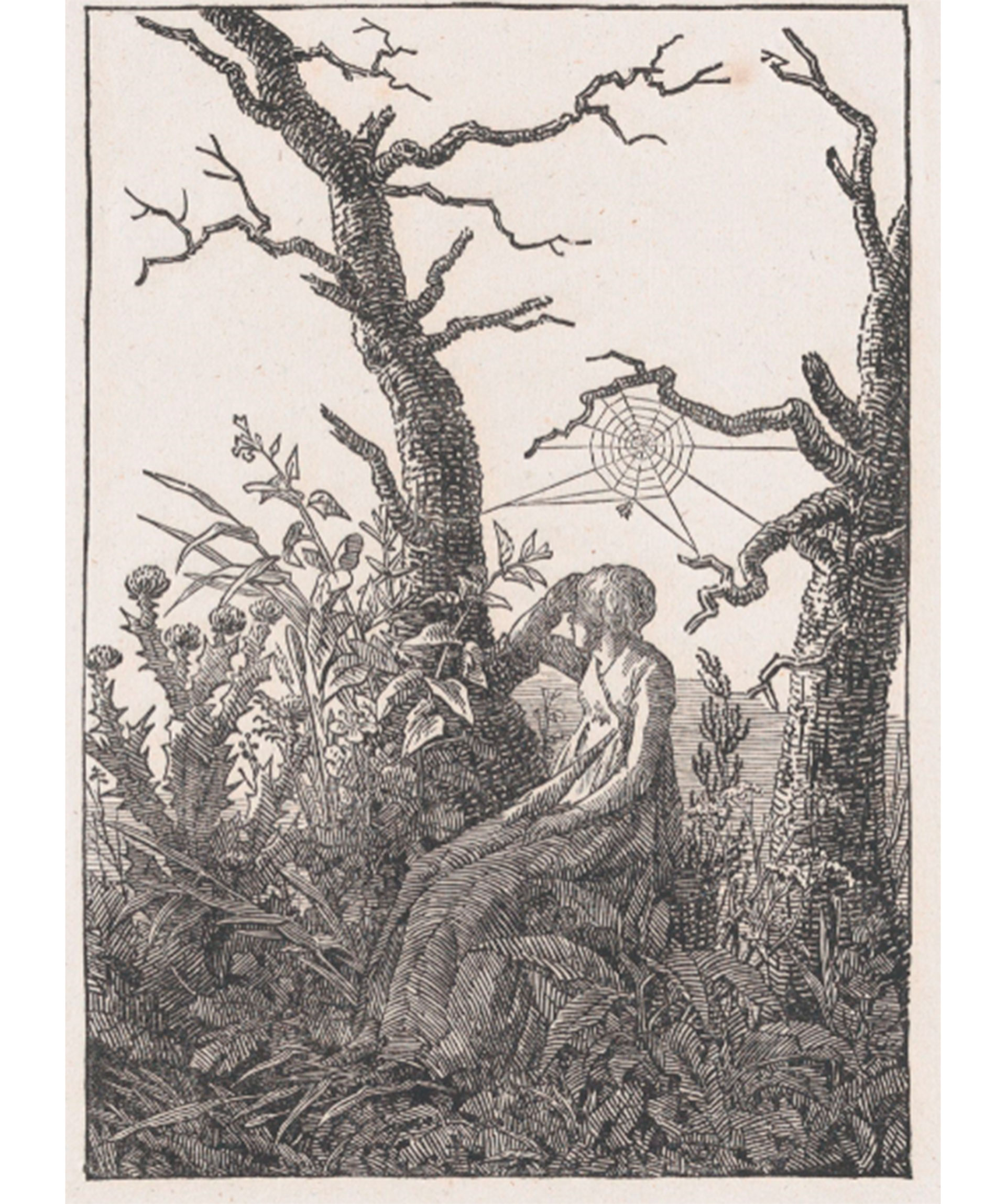

All this roundup to say that this secret voice/word, as the title of a recent book about Novalis says, is like a “nostalgia for the invisible”: invisible to the outside, nature and its mysteries, the sea for the traveler Herder and Faust himself when he says: “Run away! Go outside, into the vast region...”, and inland, in dreams, those other personal mysteries. It is also important to highlight the concept of “symbol”, for Goethe it is the poet's own function, to capture the universal in the particular. Schubert's article “The Symbolism of Nature” is followed by “The Symbolism of Water” by Friedreich. But what relationship do we find between this poetic look and the scientific look, undoubtedly an affinity unites them, they start from the same unity. Goethe himself expresses it in his work, Solger is the one who points out the affinity in time and form of Goethe's novel to elective affinity and his naturalistic texts on color theory (1810). It was at that time that he began to practice this “poetic attitude”, as he calls it, he says: “I began to observe carefully the objects that produce that effect, and I ended up realizing, to my surprise, that they are strictly symbolic objects”. And pay particular attention to strange places, this tendency to look deep in strange places was a romantic practice, which perhaps starts from the aforementioned Herder and his departure to the sea, but continues in travelers such as Humboldt, named in one of these articles, or Rugendas. The sublime landscape of nature was thus another fundamental giver of the deep, of that secret voice. Carus, the last of the authors of this anthology, was, in addition to being a doctor, naturalist and philosopher, painter and great landscape designer.

As can be seen, and we confirm this in the brief biographies that each article presents of its authors, this characteristic is repeated — almost all doctors, many of them philosophers, nature scientists, a forensic doctor, a mining engineer, theologians, pedagogues, poets, painters — and although this variety seems chaotic and heterogeneous, there is no need to to think of it like this, as we said at the beginning, a common thread links these texts, the search for that “secret voice of nature”, says Frederick Beiser, a specialist in the subject:

“In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Naturphilosophie was not a metaphysical perversion of, or derived from, normal science itself. From our contemporary perspective it is difficult to imagine a scientist who is, at the same time, a poet and a philosopher. But this is precisely what makes Naturphilosophie so fascinating and challenging, that it must be understood in the context of its own time as the science of its time”.

That is, this variety is not the mark of a dispersion but on the contrary of a unit. This way of approaching nature as a living organism was called holistic and was a reaction to the mechanism of the scientific model of the preceding centuries (15th-18th centuries, let's take into account Bacon, Descartes, Galileo, Newton, etc.), but where this paradigm break occurs is a subject that Beiser, and I I largely agree, he believes, can be dated in 1790, with the Critique of the Judgment of Immanuel Kant. In a first introduction, which he would later remove, Kant distinguishes the mere mechanical action of nature as another action of a technical type, the former is quantitative and cumulative while the latter is an artistic action (lat. ars, gr. tekné) of nature and assumes it in the formation of crystals, the shape of flowers, internal construction of plants and animals. There Kant sees that nature is not a mere mechanism, but a living, organic and finalist creation. In the Critique of Judgment, we will then be presented with the hypothesis of a nature whose unity must be considered “as if (als or b) an understanding (even if it is not ours) had equally given it”. However, the romantics took a bolder step in this approach and assumed that nature is really a living organism.

From the same year, 1790, it is The Metamorphosis of Plants, the main contribution to Goethe's botanical biology, and a first model of holistic science that in this case distinguishes itself from that of Linnaeus, founding father of botanical taxonomy of a mechanistic and analytical type. From 1735 is the fundamental work of the latter: “Natural system, in three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera and species, with characteristics, differences, synonyms, places”. For Goethe's botany, the important thing is not to segment the isolated parts of plants from the whole plant itself and its environment, but rather to understand the part in its connection with the whole. One part does not have a causal mechanical relationship with the other, but a metamorphosis in the same way reveals its constitutive essential unity, the part thus becomes a symbol of the totality, the particular of the universal. “While Linnaeus is concerned with making plants manageable, in order to organize gardens, Goethe focused on making the plant visible.” But what does it mean to “make the plant visible” in this context, then, it is a matter of capturing the particular plant in its profound universal meaning, that is, as a symbol.

Max Weber talks about the triumph of the Newtonian scientific model and associates it with a “disenchantment of the world”, that disenchantment meant the triumph of a capitalist view that takes nature as its object. While romanticism is a reaction to that look, those who are linked to these romantic trips were the representatives of budding capitalism. Charles IV asks Humboldt to send reports of the riches of America. Franz von Baaden, another author of the anthology, besides being a Catholic theologian, philosopher and physician was a mining engineer. Schubert points to this greed for money from the mysterious power of metals.

The model that guided the investigations of the forerunner Maria Sibylla Merian, those of the classic Linnaeus, those of Mutis in America, were centered on the vision of the observable and evident by empirical means; Daniela Bleichmar speaks of a “visual epistemology” as a link between economic botany and taxonomic botany. The model that guides Humboldt is undoubtedly the opposite, Humboldt contemplates “the hidden forces that make nature work”, “harmonies and occult forces enroll it in a spiritualist aesthetic”. César Aira also makes it clear:

“Humboldt had reduced these primary forms to nineteen; nineteen physiognomic types, which had nothing to do with the Linnean classification, which operates on the abstraction and isolation of minimal variations; the Humboldtian naturalist was not a botanist but a landscaper of the general growth processes of life.”

In the case of Rugendas, the pictorial is also spoken of as a function of “evoking ideas that go beyond mere visual experience” and adds “archetypes are conceived as a typology of landscape”.

We recalled at the beginning Goethe's definition of a romantic symbol, which is distinguished from allegory for several reasons: the first thing Todorov indicates is that the symbol is opaque, although its meaning is direct, without mediation of customs and culture, like allegory, the symbol is naturally based, it does not have its foundation in the cultural arbitrariness of allegory, the symbol is natural and has a strong basis in the image (Bild) not in the form as allegory. All these romantic authors do not see ways from which to conceptualize the elements of nature, they see the image from where they immediately capture the living organic unity that is nature.

Novalis himself, from which we start with the poem that opens the book, wrote a year before his death, in 1800, a long report on the lignite deposit, as well as a series of trips of geological and cartographic studies. It was in 1797 that Novalis enrolled in the Academy of Mines. “The underlying motive was to delve into the intimate link between nature and spirit, between physics and metaphysics — a link that he began to see, and which Schelling's reading and conversation with the philosopher confirmed to him.” There he studied chemistry, physics, mathematics, geology, mineralogy and issues of law related to these topics. There he took classes with eminent scientists, but in fact he was fascinated by a certain Werner, to whom he would dedicate an evocation in the character of chapter V in the novel Heinrich von Ofterdingen that deals with these subjects. The evocation of the old master in the character of the old man, der Greis, is really moving, says Novalis after thanking Providence and God: “After him, I owe everything to my old master, who long ago left to meet his own, and which I, now, cannot evoke without tears.”

In a lecture on translation that Borges gives at Harvard, after going through the virtues and problems of literal translation and its variants, he comes up with an interesting idea: “the time will come when a translation is considered as something in itself”, that translation is as important as the original, because a beauty justifies it. This highlight is for Borges “worthy of being desired with devotion”, this book is one of his deepest materializations.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs