Berta Cáceres: blood should not be water

“We are in the sights of the hit man. Our lives hang by a thread. But they're not going to arrest us out of fear. This fight belongs to the people, and will be followed by the people if we ever miss it,” Berta Cáceres told Argentine activist Claudia Korol. In the early morning of March 3, 2016, four hit men entered his house - from the village of La Esperanza, in Honduras - and took his life.

Justice found seven culprits. But they're the ones who fired, not the ones who ordered to shoot. Berta fought from Honduras for water and for life, and the struggle cost her life. She was fighting against the construction of a dam to defend the Gualcarque River, between the departments of Santa Barbara and Intibucá, considered sacred by the Lenca people. She was fighting the Agua Zarca hydroelectric project. “Of the rivers we are ancestral custodians of the Lenca people, also protected by the spirits of girls who teach us that giving life in multiple ways for the defense of rivers means giving life for the good of humanity and this planet,” she said when she was awarded the Goldman Prize, for her struggle for the environment.

Korol wrote the book The Revolutions of Berta, published by Ediciones América Libre, in 2018. “Revolutionary since she was young, almost as a child, teacher, mother of three daughters and one son, dear friend, daughter, sister, aunt, cousin, companion, internationalist, warrior of the Lenca people, pedagogue of example, caretaker of nature, rivers, forests, biodiversity, culture and spirituality and activist antimilitarist”.

In 2011 she came to Argentina for a visit and I was able to interview her. “Our struggle is for the rights of indigenous peoples and women. From the beginning we fought against teachers who raped indigenous girls in schools, although impunity is so great,” said Berta who was fighting all violence.

She was an indigenous woman who defended the women of the earth. She was a feminist and expelled bullies or abusers from her organization. But she didn't feel close to a feminism that was only for the women closest to power. “We don't like elite feminism, which is far removed from the struggle of women and the struggle for water and territories,” she said.

Today, one of his daughters, Berta Zúñiga Cáceres, continues her struggle for land, water and life through the Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH). Berta Zuñiga Cáceres' grandmother and Berta Cáceres' mother, Berta Flores López, was another wrestler and midwife. She felt safe if her mother was in her births. And their struggle continues to give birth to history.

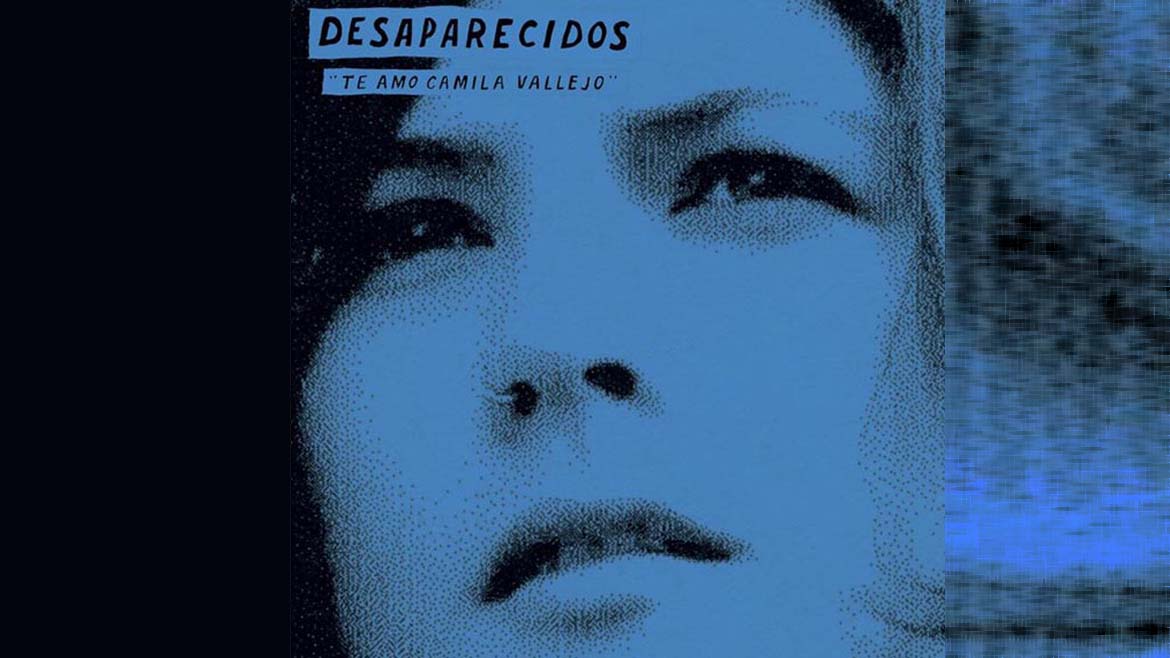

Camila Vallejo: the dog they couldn't shut up

Camila Vallejo was the student leader in Chile along with the now-elected President Gabriel Boric. She became a deputy and her image revolutionized Congress when she gave the tit on her bench to her daughter, Adela, in 2015. She was the president of the university federation and is a geographer.

Camila Vallejo was appointed as a spokesperson for the next government and already said that she does not plan to leave the Palacio de la Moneda and give a lecture to traditional media but is going to innovate on digital platforms from Twitter to Tik Tok.

She set up her government planning offices at the university as a preliminary step to management and as a sign of continuity with the youth revolt. It was the face of the Chilean student marches (in 2011 and 2012) that demanded free and quality education.

On February 28 of this year, from the headquarters of the University of Chile, she declared: “Being able to work from here as a minister fills me with pride and a lot of thanks to my alma mater”. He said: “I have many stories and good experiences in this place, many moments in what was the struggle for educational reform, for free education and for the defense of public education.”

Camila, at the age of 33, is the presidential spokesperson for Gabriel Boric's government. She is one of the 14 women who make up a majority female cabinet. Her full name is Camila Antonia Amaranta Vallejo Dowling and her beauty, self-confidence and ideas earned her a macho war. Now, for the first time, it will reach the Executive Branch.

“The dog is killed and the cam ends,” a former official of the Ministry of Culture tweeted against her. But they didn't kill the dog, nor was her career over. And her look continues to attract attention, in the appointment of the cabinet I wear a suit with a jacket and pink shorts (elegant and sexy) that caused a sensation, but beauty is also for her a tool before public opinion. “Objectively I'm pretty and I have no problem saying it, but I didn't decide what my appearance was going to be. What I did decide is what my political project is,” she told Chilean magazine Paula in 2011.

“Perhaps Camila has been very hard because she is a woman, young, intelligent and also beautiful. Perhaps, she has received advice not to be so protagonistic. 'It is frowned upon on the left that a woman is so visible'. (And why not?) Maybe they tell you that 'you should step aside and allow your teammates to give their opinion and occupy the screen'. And they do it well, they are precise and very clear in their speeches, but they do not have the luminosity of Camila, who sparked the student revolt with her impertinent spring,” said the writer Pedro Lemebel, in a chronicle collected in the book Talk to me about loves, edited by Seix Barral.

Marielle Franco: the councillor of the favela

Marielle Franco (38) was a feminist, lesbian, black, sociologist and resident of the Maré favela in Rio de Janeiro who became a councillor for the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL). She was murdered on March 14, 2018 and her femicide became the political murder of a woman, who comes from below to power, most emblematic in Latin America.

“The murder of Marielle represents the vulnerability of women who suffer threats, or their environment, when they reach places of power,” contextualized Anielle Franco, her sister and the Director of the Marielle Franco Institute. “Progress was made in arresting Marielle's material murderers. But I don't know if we'll get to the names of those who sent her to kill her,” said her friend Renata Souza and deputy for the Socialism and Freedom Party (PSOL).

Marielle is the emblem of the murder of women for disputing power. In principle it was believed that if women were empowered they would no longer be killed, that their vulnerability was because they did not know how to defend themselves, but it is not that power liberated them, real power - the one who has the weapons and the money - did not want competition.

Marielle's body was spared as a threat that explodes in the eyes of the others so that the distance between the threat and the fear is shortened, it becomes accustomed, but it becomes a shadow. The struggle illuminates his memory and so does the political fireflies that do not let the sky close for those who were not destined to win.

“Black women are not asking anyone for authorization of anything. We're not getting there. We don't back down. The people don't give up, let alone black women,” Anielle Franco defined, on her Twitter, in support of the candidacy of Francia Márquez Mina.

Ysabel Cedano: the right to choose to be a mother

María Ysabel Cedano García is a lawyer, feminist, lesbian and Quechua. She works in the organization Studies for the Defense of Women's Rights (Demus), an organization of which she was the president between 2004 and 2009. She was also Director-General for Women of the former Ministry of Women and Social Development from August to December 2011.

She is responsible for the strategic litigation to bring justice for forced sterilizations in the 1990s during Alberto Fujimori's administration. It was not about the choice of a contraceptive, but a strategy of population and territorial control in which women's decisions and informed consent were not respected. “There were crimes against women, their personal freedom, their integrity, their life, their health that also meant that many died because of the way they were treated,” Ysabel told Infobae from Peru.

She emphasizes that, since the Fujimori government, it was prescribed that a number of women should be sterilized and that caused violations of their rights: “That there were goals and quotas and that they had to comply with them so that tubal ligations and vasectomies were performed without guaranteeing health conditions and without being able to save them life in an emergency”.

Ysabel has powerful features and deep expressions, the voice soft like that of a girl who never ceases to perceive pain and of an adult who never ceases to desire love and justice. She walks in a lilac dress with slippers through the huacas, the pre-Inca ruins of Lima, between steps that show that history progressed while progress delays and the pompons that color a story that refuses -through its own fabric- to be linear.

His eyes cry when he remembers his family and, much more, silence or punishment. She couldn't say she was a lesbian because they told her she was just saying it to annoy. Not that it bothers you, but the main thing is to be able to wish. And to dispute power so that desire is a right.

A butterfly on its chest protects it among the hanging colors of a people that has on its plates the diversity that it denies in its beds. And that she also claims with the pain of the traces of shame imposed by cultural racism. Being what you are was not an option when shame is a form of submission.

She identifies as Quechua, but she is not Quechua speaking. “I don't speak it because they denied me the possibility of speaking it because of racism, because speaking Quechua in Lima was being a chola and that meant that you were going to be discriminated against, so you couldn't speak Quechua, could you? , they couldn't recognize you as an Indian.”

Yasnaya Aguilar: the multiple language and the diverse land

Yasnaya Aguilar is a researcher of mixe culture and fighter for the culture of multilingualism. She didn't know how to write her mother tongue: ayuujk or mixe. Its community is Ayutla Mixe, cradled in the northern highlands of Oaxaca. She has a degree in Languages and obtained a master's degree in Hispanic Languages from the National University of Mexico.

“In 1820, 65% of the population in Mexico spoke an indigenous language, but currently only 6.5 percent speak an indigenous language,” said Yásnaya Aguilar, as part of the celebration of the International Year of Indigenous Languages, in 2019, at the Congress of Mexico. She believes that what is linguistic is personal and what is personal is political and that indigenous languages do not die, but are killed by the State.

She criticized, in an interview with Palabra Publica: “The State, which for a long time was openly linguistic, changed the legal framework and created institutions, but they do not have the budget or the vision. In fact, there is no political will, but a willingness to hold festivals of indigenous poetry while the health system or justice system remains strongly monolingual. The inertia of how the State works does not allow it to be otherwise.”

Together with director Gael García Bernal, she made a documentary series of six short films called El tema. “The issue is so urgent that it transcends any partisan interest,” she told the newspaper El Pais. “In this area of the world, defending nature threatens certain interests. We cannot talk about infinite growth, we must rethink those ideas of development and progress,” says Yesnaya Aguilar.

Catalina Ruiz Navarro: Catalina pulls green hairs

Catalina was raised by her mother and grandmother. She is an heir to strong and independent women and as a worthy heretic she was a rebel in her childhood. The challenge she heard was “Catherine, for God's sake!” and that's his nickname on Twitter. However, there were so many attacks, persecutions or convictions that today it cannot be so exposed.

Catalina became a modern voice to denounce sexual abuse in Mexico (where she lives), in Colombia (she was born in Barranquilla where she leaves the skin of dancing so much at carnivals), in Guatemala and in Honduras. She was encouraged to say how abused those who seemed not abusers, but allies and those who prosecute her for replicating the voices of women who did not dare to denounce because they could be prosecuted.

Catalina wears huge fruit rings and puts on red makeup. He has fabulous pajamas and a magnetic presence. She talks as if she doesn't stop looking at her and is a magnet in her Volcanicas videos on Instagram. He believes in witches and dance. They are ways of saying something more than one thinks and of thinking about the alchemy that has a tradition of wisdom that goes beyond the rational.

It also renewed a feminism that was obsolete and analogue and gave it a young, pop and modern imprint. He also wrote Women Who Struggle Meet, by Penguin Books. She met many and is central to the new rise of Latin American feminism. And, like every driver, she is also punished for what she generated. She is also a columnist for the newspaper El Espectador, in Colombia, since 2008. She is the director of Volcanicas and Creadoras Camp and one of the founders of the Colombian feminist collective Viejas Verdes.

In the column “Can men break the patriarchal pact? A Feminist Analysis of Sexual Violence Among Men”, August 24, 2021, in Volcanicas, dismantles the replica of “Where are the feminists?” , when they are intended to be everywhere and “Why don't they denounce such a thing instead of denouncing something else?” , when they are intended to be silent with the argument that they should have talked about something else.

“There is something they always demand from us when we denounce sexual violence against women: why don't they talk about men who have been victims of sexual violence? And that is a very good question, although it is often asked maliciously because the purpose of asking that question is to 'show a lack of coherence' in the actions of whistleblowers, and feminists, and thus change the topic of conversation.”

“It is a fallacy that in English is called 'whataboutism', and in the classical logic 'tu quoque', one of the many ad hominem fallacies that seek to attack people to avoid refuting an argument. How interesting it would be if those who ask this question actually wanted an answer. Because yes, men are also victims of sexual violence, they have no space to talk about it and collective silence benefits the aggressors. Sexual violence is an abuse of power. Men are most vulnerable to this type of violence when they are children, for example, when they have the least power,” describes Catalina Ruiz Navarro.

“In adolescence things begin to change: men begin to receive the power that patriarchy has in store for them and, later, many abuse that power by becoming bullies themselves,” he explains. And he summarizes: “But this reality does not respond to the fact that men are inherently evil, but because men are the ones who, most often, have power over other people.”

Elisa Loncón: the Mapuche with a bulky curriculum

Elisa Loncón was elected (by 96 votes), in July 2021, president of the Chilean Constituent to draft a new Constitution. The news went around the world because she, at 58 years old, is a teacher, linguist and Mapuche activist. She is also a PhD in Linguistics and Academic from the Department of Education of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Santiago and an expert in bilingual intercultural education.

She loves Mapudungun, the Mapuche language. She is also a professor of English at the University of La Frontera, Temuco (Chile), with postgraduate courses at the Institute of Social Studies in The Hague (Holland) and the University of Regina (Canada). He holds a Master's Degree in Linguistics from the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Iztapalapa UAM-I (Mexico).

Her mother was a housewife and she liked poetry. And his father learned to read and write in a self-taught way. He has seven siblings. She recounted the discrimination she suffered in academia. “I tried to form a professional work team with non-indigenous people to present projects and I had very ugly experiences. It was even once questioned whether I had falsified my resume. I think it's a question of absolute racism; they told me I had a 'bulky resume': they couldn't believe that was my resume. Racism invalidates your human capacities”, he recounted in the book Zomo Newen by Editorial Lom.

But when he assumed the presidency of the Constituent (a position he no longer holds) he resigned it as a collective triumph. “I am grateful for the support of the different coalitions that gave their trust and placed their dreams in the call made by the Mapuche nation to vote for a Mapuche person, a woman, to change the history of this country,” said Loncón.

“This is a dream of our ancestors and this dream comes true; it is possible brothers and sisters, companions, to re-found this Chile, establish a relationship between the Mapuche people, the original nations and all the nations that make up this country,” Loncón said when she was elected.

“It is possible to dialogue with us, so that they are not afraid of us, because the politics of fear has also been installed a lot. In other words, an indigenous, Mapuche candidate is installed and there is a lot of prejudice. So, this is also a call to free ourselves from our prejudices and relate on an equal footing,” he clarified in an interview with La Tercera.

Taliria Petrone: the revolution of the daughters

Taliria Petrone is a federal deputy for parliamentary socialism (PSOL) in Rio de Janeiro. She is a history teacher, young, black, mother and feminist. She was threatened with death because her very description is a threat to power. The legislator reported on her Twitter account: “The Federal Police obtained information about a plan against me, but the government is ignoring the safety of an elected parliamentarian.” The government guarded her in Brasilia, but not in Rio de Janeiro.

Life is at risk and when life is running, women also put themselves at risk of being criticized. For being mothers and working, for not stopping working and for not stopping breastfeeding. Taliria symbolizes almost every place where putting the body is to make a difference. In a session at Congress in June 2021, which dealt with the privatization of Eletrobras (Brazil's largest electricity company), Taliria was giving a passionate speech against privatization. Her daughter was in her arms and without stopping talking, she settled down and breast-fed her.

In it so many others who do, talk and feel the hunger and attention of their baby without ceasing to do or care. However, on the networks his gesture was criticized by some as “unnecessary” or they asked him why he hadn't left it somewhere or had gone to a milk farmer.

She replied on Twitter: “And who do you suggest I leave my daughter working more than ten hours with?” . Women deputies work, but they are not considered as workers. They don't even have maternity leave. Therefore, the presence of Taliria and her daughter in Congress is a political, labor and trade union act.

“We are working on the issue of political motherhood because those spaces were designed to exclude women,” they say from their office. Women do not arrive alone, but also - in order to do politics - they have to do it with others and, often, with their daughters and sons in tow. It's a form of care mandate.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs