Wars and trains are intimately linked. The film was in charge of telling these stories masterfully, from David Lean's mythical “The Bridge over the River Kwai” to “The Railway Man” by Australian Jonathan Teplitzky. Many more showed the operation, always on time, of the British railway system and the London Underground under Nazi bombings. Now, a new chapter of this epic on rails is taking place in Ukraine. Despite the bloody Russian invasion and the control they maintain in sectors of the east and south of the country, the Ukrainian train system remains operational. The manager of the Ukrainian Railways, Oleksandr Kamyshin, and five of his men organize the overall operation. Machinists, station managers and technicians roll them as a patriotic “obligation”.

Over the past two weeks, Ukrainian trains carried 2.1 million people, the vast majority fleeing to the west of the country and attempting to cross into Poland, Hungary or Romania. They do not reach the usual 160 kilometers per hour before the war and often have to be stopped for a few hours to repair the tracks hit by enemy missiles and mortars. But they maintain an honorable average of 60 kilometers per hour. The latest feat of the Ukrainian railway workers: they took from the Polish border to Kiev the prime ministers of Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovenia to meet with President Volodymyr Zelensky. A blow to global public opinion that shows the European Union's full support for the Ukrainian democratic government. Diplomacy on rails.

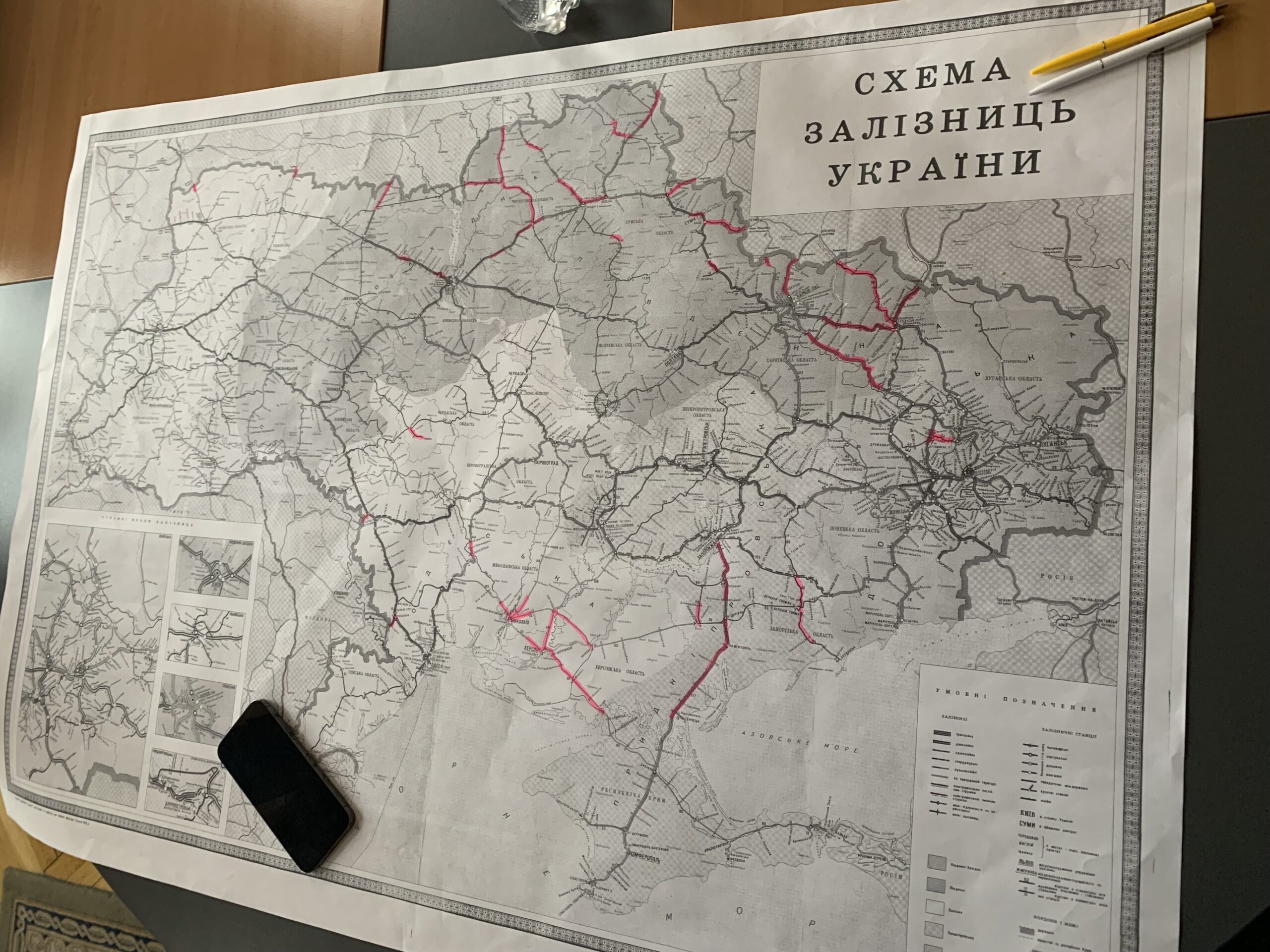

The nerve center of control is also in constant motion. Manager Kamyshin, 37, and the five engineers and administrators who accompany him operate from a train that does not stay more than a few minutes in the few stops he makes. Thanks to an old closed-circuit telephone system from Soviet times, they maintain contact with all 1,450 stations of the system. “The strategy is to move fast so you don't get caught, and not spend a lot of time in one place,” Kamyshin explained in an interview with CNN. Faced with maps and attending communications with those responsible for the different formations on the move, it is the closest thing to a general on the war front. His locked beard, the hair cut flush on the sides of his head and the ponytail that reaches his shoulders, make him look more like a rock star than an executive. He also left his narrow-cut suits to be sheathed in a military uniform.

The greatest concern of Kamyshin and his “generals” is to bring humanitarian aid to cities besieged by the Russians. The strategic port of Mariupol, on the Sea of Azov, is now the priority. There are tens of thousands of civilians trapped there. The corridors agreed to get these people out are constantly bombed. They don't have water or food. There is a train with food and water and fuel tanks on the outskirts of the city waiting for permission from the Russians to enter. He's been waiting for 48 hours. There are desperate calls for help on social networks and Kamyshin is looking for an alternative: the possibility of getting help into small locomotives used to repair roads. He's sending them from Ternopil on the other side of the country. “If we succeed, it means that we beat the Russians, at least in Mariupol,” says the Bussines Insider reporter who interviews him.

Another pride of railway workers are trains equipped to transport the wounded to hospitals and which also have rooms for carrying out emergency operations. “We received help from abroad, but we were able to prepare them in a matter of hours,” explains one of the engineers in another report with the Telegraph newspaper in London. The vast majority of the 231,000 employees that the company had before the war are still in their jobs. They are part of a “mini army”, a mixture of railway workers and popular militiamen, who guard and control the railway network. They are also on the permanent move. Kamyshin thinks that's the key. Don't stay locked in one place. He and his closest collaborators were offered to operate from the same bunker where President Zelensky is in Kiev, but they rejected him. “Trains are controlled from other trains,” says the manager. “Our logic is very simple. If we have employees who are working at this station, and we think it's safe for them, then we have to go too,” adds Kamyshin.

Another concern of engineers is the huge number of passengers traveling in each formation. Obviously, no ticket or payment is required and they cannot prevent desperate fleeers from being left on foot. In the early days of the evacuation from Kiev, Ukrainian soldiers had to fire fire into the air to allow the crowd to leave a convoy with people traveling to the roofs of the carriages and exposed to temperatures of 20 degrees below zero. “The decision to let as many people as possible on trains has been difficult because any unfortunate event would affect many more people. But we had no choice,” Oleksandr Pertsovskyi, Kamyshin's second and responsible for the company's passenger service, told the Business Insider.

Ukrainian railway workers also suffered casualties. As of Tuesday, 33 employees were killed and about 150 injured. The worst moments are experienced by those who repair the tracks. They often have to do it under enemy fire. If they destroy a bridge, they have to reorganize the service by other sections. There are even tracks in the east of the country, in the separatist areas of the Donbas, and on the connections with Crimea in the south, which are controlled by the Russians and they know that they managed to operate some trains. The important railway center of Volnovakha is in Russian hands.

They know that it is very likely that the Russian advance will spread in the next few hours and they will lose control of many other railway circuits. Russian planes are bombing stations and convoys to prevent the movement of military supplies and the evacuation of civilians, who within cities may end up being a bargaining chip for besiegers. Social networks are crammed with messages with alternatives to trains. “Thank you so much for saving us,” Konstanty says in a Telegram chat. “The train to Lviv passed through here and it's on schedule,” warns Kiki, who lives in a house next to the tracks in Poltava. Kamyshin and his family can receive these messages thanks to Elon Musk's Starlink system, but they use it to a very limited extent because the enemy can detect their movements.

And in the midst of human dramas, Kamyshin and his men are also trying to bring out Ukrainian agricultural production, which is what generates the much-needed euro currency, and which until now came out through the Black Sea ports, already dominated by the Russians. They are sending freight trains to the west connections through Poland, Romania and Hungary. But they have one drawback: the gauge. There are differences between European networks and grains have to be reloaded at borders.

“Even I can't believe that the system is still functioning after 20 days of war. 'It's a miracle, 'President Zelensky told me the other day,” says Kamyshin. “Well, let's keep trying until we have the necessary strength.” These men have not seen their families since February 24, when the invasion began. They were very worried until this weekend they finished sending their wives and children out of the country. Kamyshin dismissed them on platform five of Kiev Central Station. Trains from all over the country pass through this magnificent art nouveau station opened in 1904 under the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph I. “Until now, it was for me one of the most beautiful stations in our company. But after dismissing my family it became the saddest,” confesses Kamyshin, the magician of the tracks.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs