It was five o'clock in the afternoon of Thursday, May 23, 1901, when Commissioner Bucheton, of the police of Poitiers, France, knocked on the door of the Monnier family mansion, located at number 21 on Calle de la Visitación. The employee of the family could not refuse to open. Bucheton was accompanied and with an order from the Paris prosecutor, Monsieur Morellet, to review the elegant house. The excellent reputation of the aristocratic family was not going to stop them.

The employee, after consulting the owner of the house, replied that Madame Louise Monnier, 75, was in bed, they would have to go talk to her son Marcel - 53 years old, doctor of law and former public servant - who lived on the opposite property.

The cops crossed the garden and the rose bushes and came to his door. The butler tried to discourage them, but he didn't succeed. Marcel had to attend to the uniformed men who were willing to clarify a horrible complaint without a signature that claimed that an adult woman was abducted in the family house.

Once the authorities entered the mansion, they were checking, one by one, the rooms on the ground floor. They found everything in perfect condition. They decided to continue the search on the second floor. They climbed the great staircase and, again, entered each environment. They didn't find anything unusual until they came across a door leading to an attic. It was closed to lime and edge with a thick chain and a padlock. They demanded that it be opened, otherwise they would have to call the judge. The mistress of the house ended up agreeing.

As they opened the old wooden door, a nauseating stench stuck wet on their faces. The officers tried to hold their breath. They wanted to vomit. In complete darkness, at the bottom of the attic and on a stinking mattress they came to see the shadow of a gray skeleton that was beating naked.

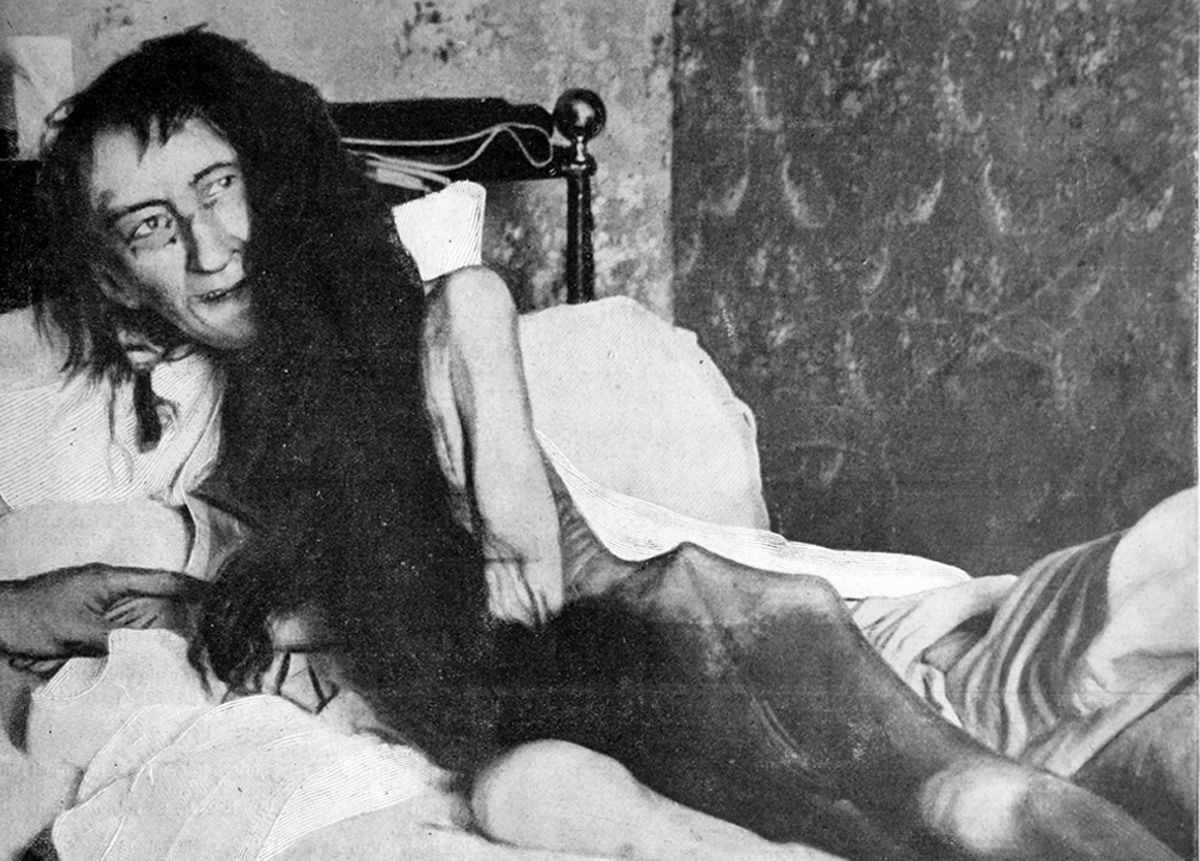

They immediately broke the chains of the blinds and tore the canvas that covered the windows. The sun crashed on the filth and the rats and cockroaches rushed to take refuge. The police then observed that this figure, like twisted wire, appeared to be a woman. He wasn't wearing clothes. A thick tuft of dark hair fell to his ankles and had claw-like nails. She was surrounded by scraps of food, urine, worms, insects and her own feces.

Blinded by the light, the creature snarled closed its eyes and screamed as it tried to hide its gnawed bones under the blanket.

It was all that was left of that woman they were looking for. Marcel Monnier identified her as his sister.

Blanche Monnier, once young and beautiful, was 52 years old that day when she was rescued from hell with a delay of two and a half decades.

Mom, a fierce jailer

There are mothers and mothers. Blanche Monnier's would not be the one we would choose to have, but it is already known that when it comes to mothers no one has the opportunity to choose.

Blanche was born in Poitiers, France, on March 1, 1849, into a prosperous and respected family in the city. Louise-Leonide Demarconennay, her mother, was a socialite of the time who frequented parties, charity galas and cocktails. His father, Charles-Émile Monnier, was Dean of Arts at the University of Poitiers and professor of rhetoric. The marriage that belonged to the local aristocracy practiced Catholicism and was declared monarchical.

Blanche's older brother, Marcel, had been born just a year before her. As early as adolescence, Blanche had begun to have mystical breakdowns, nervous problems and eating disorders. Besides, his mother's authoritarian character didn't help.

In 1874, Marcel married a Spanish woman of noble origin and, due to her employment as a civil servant, she moved. He lived for several years in other cities of the country.

The most serious problems began for Blanche, who had also become a socialite like her mother, when she fell in love with the “inconvenient” person in the eyes of her family.

Although she had had several suitors, she chose a Protestant and Republican lawyer, who took her many years. The man lived in a nearby house and was bankrupt. It was the complete opposite of what Louise and Charles-Émile intended for the beautiful young woman.

When Blanche announced to them at age 26 that she intended to marry him, her frightened parents opposed it.

Charles-Émile Monnier had just lost his position as Dean of Letters and the rift between Republicans and monarchists had deepened. For a republican who was protestant and penniless to pretend to marry Blanche was the worst thing that could happen to them.

It is believed, although it was not proven, that what would have caused the disaster to have been a clandestine pregnancy of the couple. Blanche's baby would have died at birth or they would have made him “die” as soon as he was born. That was said. In addition to the kidnapping, in this story, there could be a murder.

With Blanche depressed, her parents would have decided to rip off any idea of their daughter's uprising by locking her up in the small attic of the house. What could have started as a cruel reprimand would have been transformed, over time, into brutal captivity.

Blanche's father, weak in character, did not dare to contradict his fierce wife and let her act.

By 1876 Blanche Monnier had disappeared from the face of the earth for most of his acquaintances and friends. Even her boyfriend didn't know anything about her.

To justify Blanche's absence, the Monniers simply lied. First, they said he was in boarding school in the UK. As the years went by, they had to come up with another excuse for their absence: they said that Blanche had settled in Scotland. In the meantime, they continued their usual life and, at some point, even cried in public pretending that they missed her.

Blanche's mental health, trapped in her own home, deteriorated more and more. He saw ghosts, took off his clothes, refused to eat. In the shadow of existence and under the command of his unshakable mother, Blanche was consumed alone, hour after hour, minute after minute.

The domestic servant of the house continued to work as usual. How much they knew and how complicit they were in what was happening, who knows.

Charles-Émile died in 1882 without opening his mouth about what had happened to his daughter. No one asked about the young woman they believed abroad anymore. That unaccepted boyfriend died in 1885 without suspecting what might have happened to Blanche.

In 1891 Marcel returned to live in Poitiers and settled in a house opposite that of his widowed mother. Discussions about what to do with Blanche would have been frequent around this time. Marcel was a man full of hobbies and, also, a little disturbed and naïve. Madame Monnier always won the bracelet to keep hiding Blanche.

It was incredible that no one in the house talked. It was a secret open armored car.

In 1896 the person in charge of Blanche, Marie Poinet Fazy, died. Blanche was increasingly neglected in her captivity.

In 1899 Madame Monnier decided to take two new employees for the house: Juliette Dupuis and Eugenie Tabeau. That decision would be the beginning of the end of the “family secret”.

The revealing letter

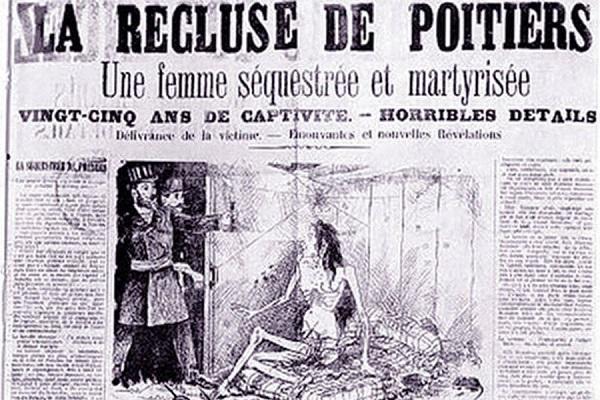

Had it not been for an anonymous letter, no one would have ever found Blanche Monnier in his impregnable tower. That letter was received by the Attorney General of Paris, Monsieur Morellet. In it he read: “Mr. Attorney General. I have the honour to inform you of an exceptionally serious event. I am referring to an old maid who is locked up in Madame Monnier's house, half-starved and has lived in a rotten bed for the past twenty-five years, in a word, in her own filth.”

Morellet could not believe that these words were true, but he had that house in Poitiers searched anyway.

Someone had finally taken pity on Blanche.

The very serious accusation reached the chief commissioner of Poitiers, Mr. Bucheton, who went with three of his agents on the same day to the street of the Visitation.

So it was that Blanche appeared still alive, but with his health and mind perpetually ruined.

The same police officers told the press: “The woman seemed to suffer from extreme malnutrition. She was lying, completely naked, on a rotten mattress. It was surrounded by a crust of excrement, pieces of meat, vegetables, fish and rotten bread. We also saw shells and bugs running across Miss Monnier's bed. The air in the room was so unbreathable that it was impossible for us to continue investigating.”

Arrest to horror

The day after the discovery of her daughter, Louise Monnier received public derision. Her neighbors, those who had known how to respect her, rebuked her on the street when she was arrested. They shouted revenge.

The widowed aristocrat, impeccable in her black-and-white checkered robe, and her son, had been arrested.

Louise Monnier ended up confessing that, worried that her daughter would associate with a “failed” man, who would dirty the family's honor, they had decided to lock her up until she assured them that she would refuse him. But, then, things went on in time. As an excuse she claimed that her daughter refused to leave the room, that her mental health had worsened after a very severe fever, and that Blanche refused to eat and dress.

Louise Monnier couldn't bear the displeasure of being discovered. Two weeks after she was imprisoned, on June 8, 1901, a heart attack ended with her.

His son Marcel Monnier was the one who ended up being tried for his complicity in his sister's captivity.

The trial began that same year and was carried out by Judge Du Fresnel. The Poitiers room was filled with an audience eager to know the backdrop of the case that shocked France.

One of the witnesses to Blanche's release stated: “As soon as we entered that room, we saw, in the back and lying on a bed, his head and body covered with a repulsively dirty blanket... a woman who Mr. Marcel Monnier identified as his sister, Mrs. Blanche Monnier. The unfortunate woman was completely naked on a bed of rotten straw.” Of the rest of the house he said: “The dining room was well furnished, the kitchen was well maintained and the staircase was clean. Everything was in place. The old lady Monnier was dressed in a checkered robe.”

The defendant defended himself by saying that he had tried to place Blanche in an asylum, but that his mother had always refused on the grounds that this could be frowned upon by society. In addition, she assured that her sister could have left the room when she wanted to, but that she did not do so because of her mental problems.

During the trial, Blanche's mental and physical disorders were enumerated: hysteria, schizophrenia, anorexia, coprophilia and exhibitionism.

The defense lawyer assured that his client had not exercised violence against his sister and that strictly speaking it could not even be said, let alone prove, that she had been kidnapped: “The fact of closing a door behind someone who has no intention of leaving is not an act constituting a crime,” he said. In addition, she explained that her sister did not live with Marcel, but with her mother.

On October 11, 1901, he was sentenced to fifteen months in prison. It should be borne in mind that, at that time, there was no notion in the penal code of “not assisting a person at risk”. It was also known that he also suffered from that disease of his sister: coprophilia, which made him have a special attraction for smelling human excrement. He himself said that he often read the newspaper in that infected room where Blanche lived.

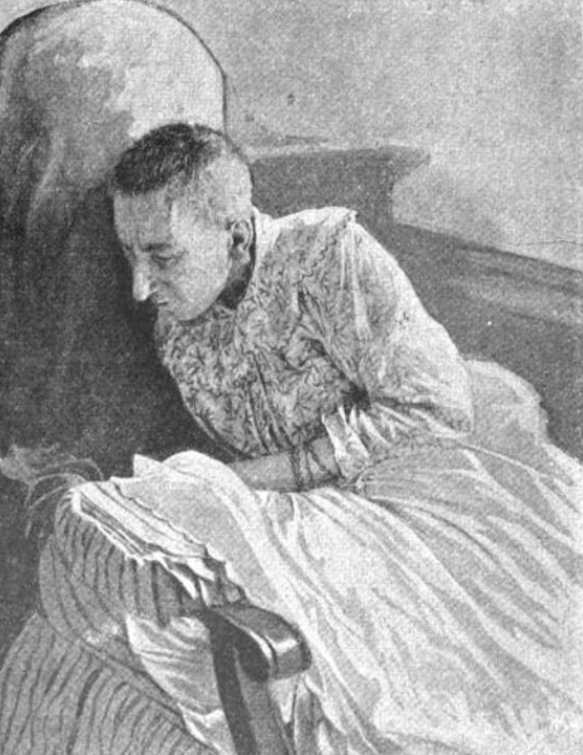

For her part, after being rescued, Blanche was referred by ambulance to Hotel-Dieu where she was treated by the nuns. After so much confinement I had both body and soul crumbled.

When they arrived at the institution, the first thing they did was weigh it: they discovered with horror that the scale did not even score 25 kilos. She was so weakened that she couldn't stand alone.

The photographs of Blanche's find taken by the authorities were published by the newspaper L'Illustration forty days later and after many discussions. In the images the woman was a human waste with eyes.

On June 11, 1902, Blanche was transferred to the Psychiatric Hospital in Blois. He went on to live in another type of confinement. Clean, shaved and well-fed, her mind never returned to the world of normality.

His very sad life ended slowly, in that same hospital, on October 13, 1913. He was 64 years old.

That year also died his brother Marcel, who lived in retirement in a mansion in the Pyrenees. There were no longer any direct witnesses to the events.

Family secrets

Discussions about the prolongation of the cruel confinement continued to float French public opinion. Was it true that Blanche did not want to go out because of her mental problems? If so, why the chains and the lock? Or had her mother kept her locked up by force because she was ashamed of her and her decisions? Did he really suffer from everything they said at the trial? If it was true that she was ill, why had she chosen to lie rather than place her in an institution? And, the most intriguing question, who had written that anonymous letter that returned Blanche to the world of the living? Who had his conscience weighed down?

To investigate this last unknown, we have to go back to 1901 when the person in charge of the Monnier mansion, Madame Renard, died. The old woman had driven the property and employees of the family with a strong hand. When she disappeared, the road to Blanche's liberation began to take shape.

In her absence, one of the junior employees, Juliette Dupuis, dared to do something that had not been allowed before: to introduce her lover, a French lieutenant, into her room at night. After one of those evenings, Juliet would have revealed to the military man the dark secret that was kept in the attic of the family home. It was May 18, 1901.

Five days later the prosecutor received the anonymous letter. For this reason it was believed that the author of the same was that lieutenant by the name of Jean Luc.

A clandestine romance had kicked off for the rescue that would scandalize France.

***

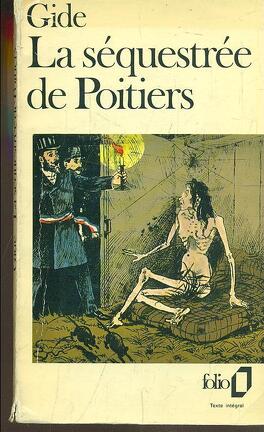

Blanche, captive, ill, mistreated and hidden from society by her family, had no chance of happiness. But at least, we can say that it was not forgotten. In 1930 its story was captured by the fine pen of the writer André Gide (who was in 1947 Nobel Prize for Literature), in his book entitled The Kidnapped of Poitiers. It wasn't the only book, there were several more.

Living in the memory of some is no comfort to anyone, but something is always better than nothing.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies