Throughout his first presidency, Hipolito Yrigoyen maintained his finance minister, Domingo Salaberry, who would never know that, at the beginning of the 21st century, he would lead the ranking of finance ministers who accompanied the president throughout his term.

Born in the city of Buenos Aires on August 14, 1879, he was the third generation of a family of treasury consignees, founder of Salaberry Bercetche & Cia. Juan, his Basque grandfather, had arrived in the country in 1848 and started in the cattle business. He was succeeded by his son Juan Francisco, who for twelve years was on the board of directors of Banco Español del Rio de la Plata. He died surprisingly in 1908, at the age of 40.

In 1900, Domingo Salaberry graduated as a lawyer from the University of Buenos Aires. Between 1913 and 1914 he was president of the Center of Shipping Agents for Producers of the Country.

When his father died, he intervened in the public collection to build, in his memory, a hospital in the Mataderos neighborhood. Juan Francisco Salaberry Hospital was inaugurated on September 3, 1915. It was located on Juan B. Alberdi, between Cafayate, Pilar and Bragado. It doesn't exist anymore. In that building, there is a carriageway.

Affiliated with radicalism, in 1914 his deputy diploma was rejected by the province of Buenos Aires, although he joined in early 1916. He resigned from the bank to take office on October 12 of that year.

Until then, the men who would make up the cabinet had not held public office. “The country is of the opinion that ministers, with exceptions, are worthless. The one from Public Instruction has the mentality of a primary teacher from inland; the Guerra is a kind and silent civilian, with no known aptitude and who is credited with the adherence of a faithful dog towards the president; the Treasury is a consignee or intermediary in the purchase and sale of livestock,” the writer acidly enumerated Manuel Galvez. In the face of criticism, Yrigoyen shrugged. “I don't need wisdom, but honesty.”

De Salaberry hoped that it would work for measures that would improve social justice, and let it do so in the economic field.

The new minister did not have to do too many accounts to know that the government did not have money, that it accumulated a floating debt of 500 million pesos and that it was facing maturities of 80 million. Even so, Congress opposed taking a loan. They also rejected the creation of an agricultural bank and a bank of the Republic. A project for the creation of the merchant marine, the expansion of the railway network in the center and north of the country and the nationalization of oil, recently discovered in Comodoro Rivadavia, were also not approved. Only in 1927 would deputies approve the bill related to hydrocarbons, but the senate would not deal with it and then the tragic coup of September 6, 1930 ensued.

In the search for domestic funding, the government tried to create the income tax. With the proceeds, the debts of the State would be paid. But they didn't approve. In what was successful, what until then represented an unprecedented experience in the country: the application, in 1917, of mobile retentions, which resulted in the cheapening of food.

What would become a personal disgrace for Salaberry would be the law of expropriation of sugar. In the message that Yrigoyen sent to Congress on August 10, 1920, along with the bill, he stressed his concern that the price of sugar would rise above normal values and, knowing of the existence of an exportable surplus, requested authorization to expropriate twenty thousand tons of sugar to sell it, at low cost, to the population.

Despite the fact that the anti-personalist radicals - opposed to Yrigoyen - had made common cause with the Conservatives, the bill was approved in both chambers. Over the months, a complaint arose against Salaberry himself. They accused him of benefiting the Salaberry Bercetche house, the family business, in an arbitrary distribution in sugar quotas. In addition, they questioned him about handling the fruits in transit and in other unclear maneuvers involving the exchange of the gold of the legations.

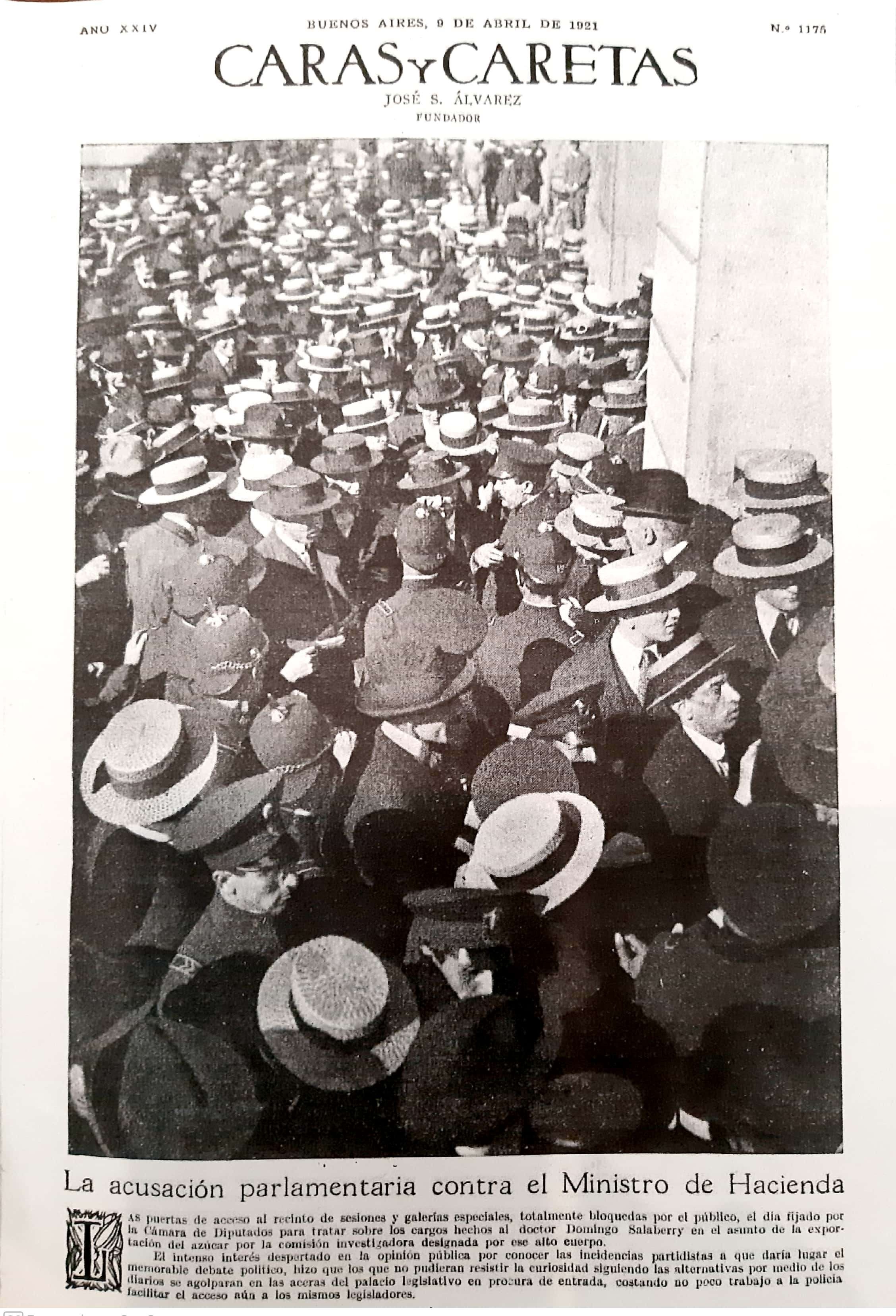

In March 1921, a commission of inquiry was formed in Congress. Salaberry, convinced that everything was the product of a maneuver devised by the conservatives, insisted on his desire to attend the congress to defend himself in person, but the president would not allow him to do so. For the president, these were situations that officials might be exposed to.

Being innocent, he must have endured being called a thief. Although justice ended up dismissing the complaints, but with suspicions flying over the air, Salaberry committed suicide on November 11, 1923. He was 44 years old.

His wake was attended by Marcelo T. de Alvear, who at one point had echoed these accusations, and who now, with his presence, endorsed the innocence of the former minister who, in his desperation, saw suicide the only way out.

KEEP READING:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs