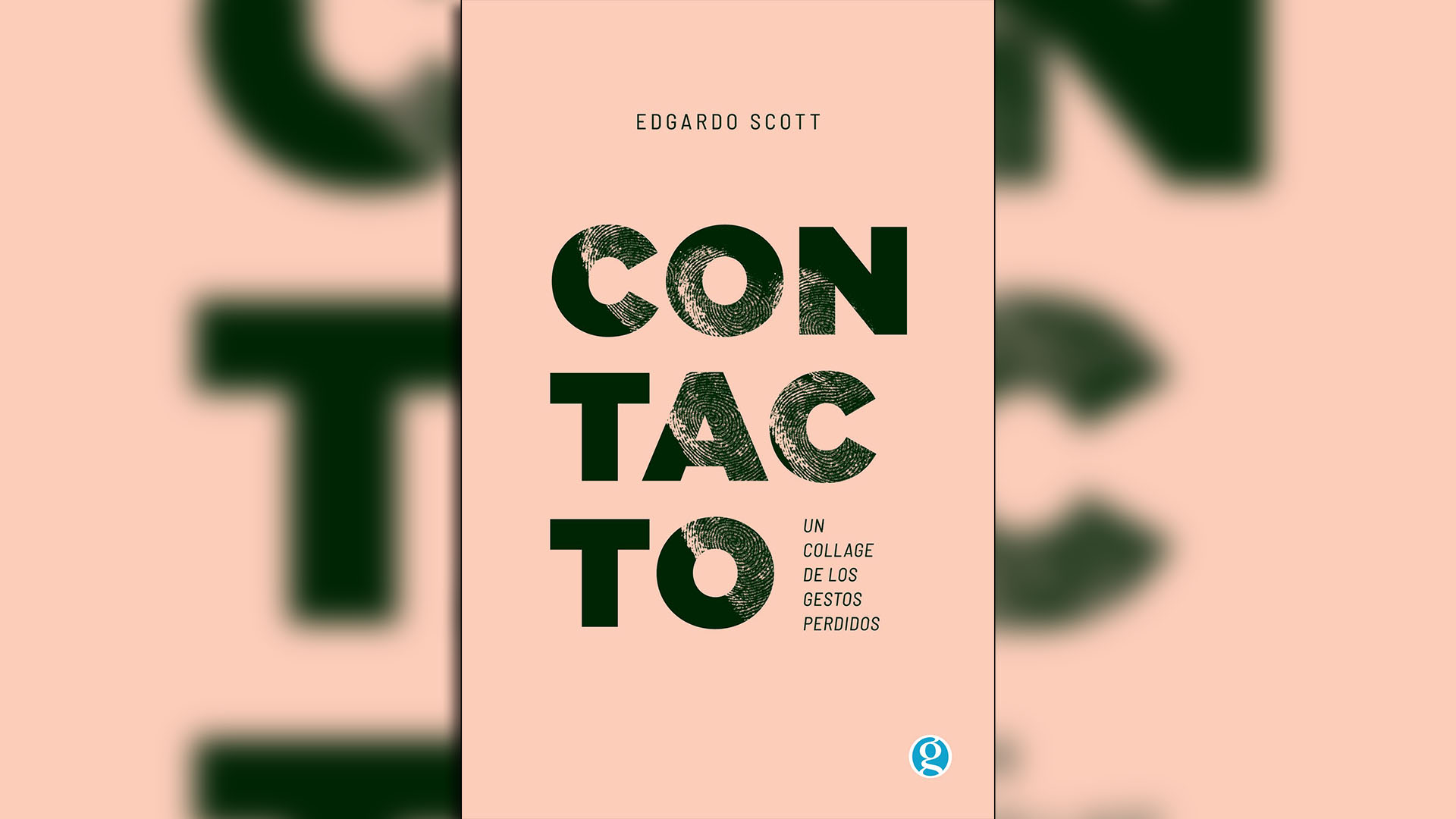

The book Contact: A Collage of Lost Gestures, by Edgardo Scott, is born from the impulse of the writer in full confinement, the anguish over the confinement, the virus or what could happen, and from his desire to write a work in relation to all the gestures of contact “threatened” by the pandemic, including the latest and most important “is the gesture of the word,” explains the author.

Contact: A collage of lost gestures (Godot Editions) is a delicate text, pleasing to the senses: a harmonious chain of references from literature, cinema or music that Scott finds in his personal archive, library and Google. Before embarking on his writing, he had finished translating Dubliners, a “very hard work”. The author born in Lanús in 1978 and based in France points out that the essay is “the most open genre, because it is always vulnerable to that radar, those 'notes' that we write take all the time. In the essay, those notes are quite a music when you are writing,” he says.

Scott is the author of Not Enough You Look, It's Not Enough That You Believe (2008), the storybook The Shelters (2010), and the novels The Excess (2012) and Mourning (2017).

— Is Contacto planned as a book of impressionist essays to create a rapprochement with readers?

“Yes, there is something impressionistic, of course, because essays always appeal to a form that is defined by a particular emotion, there is no other basis, that is why associations are so diverse in every way: in genres, in times, in proximity or recognition. I had written this way both in Caminantes and in the book about Stevie Wonder, with variations and peculiarities, of course, but what they have in common with Contacto is perhaps this of the approach with the reader. Something that I admire — and steal — from guys like Luis Gusmán or Ricardo Piglia or even in María Moreno or Juan Forn, that unpredictable hodgepodge where there are no hierarchies. What we call culture today, that scam, that deception, is a bit of that.

— Is there a new way to contact social networks and Internet searches?

“Yes and no, I think. That's been at stake since the start of the Internet, isn't it? On the one hand, who doubts it, has allowed us to intensify and extend contact, but on the other it has also served as an even greater form of isolation and alienation than television (which was its great preparation or training).

- Does the word, the image, supplant that physical contact that the rest of the animals have?

“Well, that could be better explained by an ethologist, surely, but I always remember that essay by John Berger, “Why we look at animals”. In animals there is no contact because there is precisely no word. That's why we talk about mating and not sexuality, let alone eroticism. Contact has nothing to do with the body or the physical, or rather, the body and the physical, the sensible — Saer or Blanchot blow me — are defined by the word. That is why in the list or inventory of “lost gestures” in the book, the last and most important, is the gesture of the word.

We used to talk about the Internet and social networks before and we would have to think about what place the word has there, right? There are devices — I think of Twitter, for example — that are closer to code, to the coagulated word, to the slogan or advertising, to the holofrase. And perhaps that is why the image becomes supreme, because there is a simultaneity in the image, a suggestion that the word, always unfinished, does not possess. That is why I think that one of the things that is happening is that it is changing — again, of course — but in a notorious way the way we read. There was a reading linked to the signifier, the meaning and the object (and nonsense, of course), to put it quickly, in which many of my generation were trained (perhaps we are the last ones with that operating system, haha) that I see is on the verge of extinction due to a reading either more impersonal, very democratic and progressive or absolutely taken by the taste, by the sensation and, therefore, fable of all this tremendous reideologization of the market in which we are now.

— Does the new normal tend to “contactless” as the closing of your book thinks?

“Undoubtedly, and the old normal too. That was one of the driving forces of the book, to be able to insist that what the pandemic unleashed or fully catalyzed in relation to contact was already happening. We still don't know what this “new normal” is going to be like, this post-pandemic era, because we don't quite get out yet, what's more, it would just seem that we are dating, but we also had this illusion a couple of times before. In any case, there will be a time, sooner or later, when we will get out of this, and we will obviously be able to see the effects. And right there we will also see “what was it for” all this. Where does it leave us. But teleworking, for example, or the health and biological priority in relation to social control is clear that they are irreversible variables in the medium term.

— Does the Barthesian spirit fly over in the descriptions of the photos?

“They told me, and it's very crazy, because in other books,” I remember the essays that are like embedded in my novel The Excess, I had Barthes very much in mind, but not in this book. In fact, now, for the extension of Caminantes in the Spanish edition, I was working with the scene where Barthes died, who ultimately died “walking”, crossing the street; bah, from that accident everything got complicated.

But I was telling you, in Contacto I didn't have Barthes so much in mind, although obviously I already have him incorporated; besides, for my generation it was a canonical, obligatory and celebratory reading, because those who trained us were already coming full with Barthes, from Sarlo to Alberto Giordano, or in my case, that I met him at the faculty, working in the chair of Hugo Vezzetti.

— Do the slow ones have to come back, that way of dancing in touch that your book talks about?

“They would, of course. But I don't think they'll come back. Unless there is some rhythm or some clandestine tribe that segments them and makes them fashionable. Let him reinvent them. But if that happens, it will be in the catacombs, in clandestine parties, I think that Contacto also shows a little that, that there is a place always possible, especially in fateful moments, in those dark, persecutory moments in history, and it is the place of resistance. Today, when power is camouflaged behind or instrumentalized certain minorities, we should claim the place, always minority and even marginal, of resistance.

Is there a contact after death?

“Of course, I think that is also in the book, based on that great infamy that has been that you cannot accompany the dying and dismiss the dead. Again, that was already in The Odyssey, there is also a “paradigm shift” that was already prevailing; a relationship with anesthetized, denying, childhood illness and death. I like the way Sebald thought about it, on the other hand, the dead and the living inhabiting the same house and going from one room to another, visiting each other. But the dead are much more real and definitive than we are. The dead you kill... etc.

—Argentine literature, national rock and, in particular, Julio Cortázar occupy a central place in the book...

“Well, that's the part where I can quote by heart, the most personal archive part of the book, because both Argentine literature and Argentine rock are my strongest brands. Yeah, it wasn't premeditated, but I liked that secret causality of starting and ending with Cortázar. I guess that's where the experience of living in Paris gets in, where the ghost of Cortázar for any Argentine and Latin American writer is very strong, inevitable, it forces you to reread it somehow.

With regard to Argentine rock, now that it is out of fashion, now that we are beginning to have the syndrome of tango men, of old music, I think it is where one can most capture its lyric, its poetics, precisely as a break and continuity at the same time of popular genres such as tango and folklore.

I'm not saying anything new. But I think that now it is quite a challenge for those of us over forty to see that this genre, which was the symbol of youth, of the new, loses its validity or, again, returns to the under. I think the best thing that can happen to Argentine rock, Argentine literature and my generation is that: going back to the under. Recover, precisely, that contact.

Source: Telam S.E.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs