Bullying and school violence (bullying) have become endemic and global psychosocial phenomena, which inhabit schools and which also offer an inverse criterion to the scientific theory of biological evolution: they involute. Based on the worldview that violence is fundamentally cultural, there is now evidence among academics that school violence impacts not only the integral health and self-esteem of the victim (in the school context, the student) but also — and directly — on the collective learning of students.

If we add to this painful scenario the effect of a pandemic due to a new virus that hit the globe - two years ago - the balance of so much social disruption is that not only did the gaps in access to technology and education widen; but also technology seems to have perfected harassment school.

The question that resonates here is: What about coexistence in my school? Does each school know its own climate of coexistence?

Schools are very different from other types of organizations, but also very different from each other . The best programs to prevent and intervene these phenomena that boycott the school climate and that affect performance and health, not only of the victim but of the entire school, know that the response must be educational, complex and persevering.

A few weeks ago, the heartbreaking story of Drayke Hardman, the 12-year-old boy who committed suicide in the city of Salt Lake City, United States, after being bullied in school, shook the whole world and came to confirm everything. His parents, Andy and Samie Hardman, spread a dramatic letter in which they shared it and exposed the story of their son to create awareness of the terrible consequences that bullying can have.

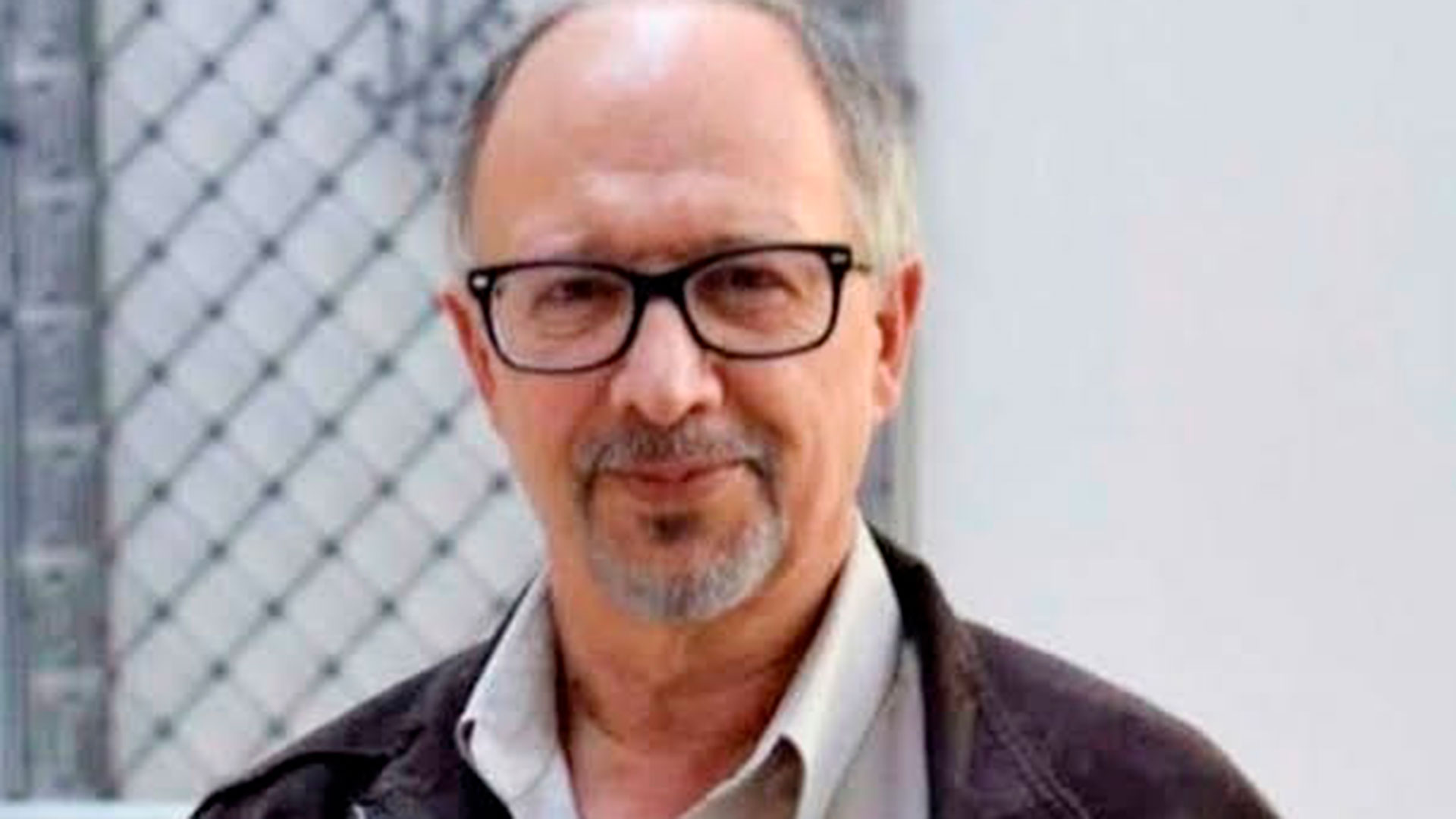

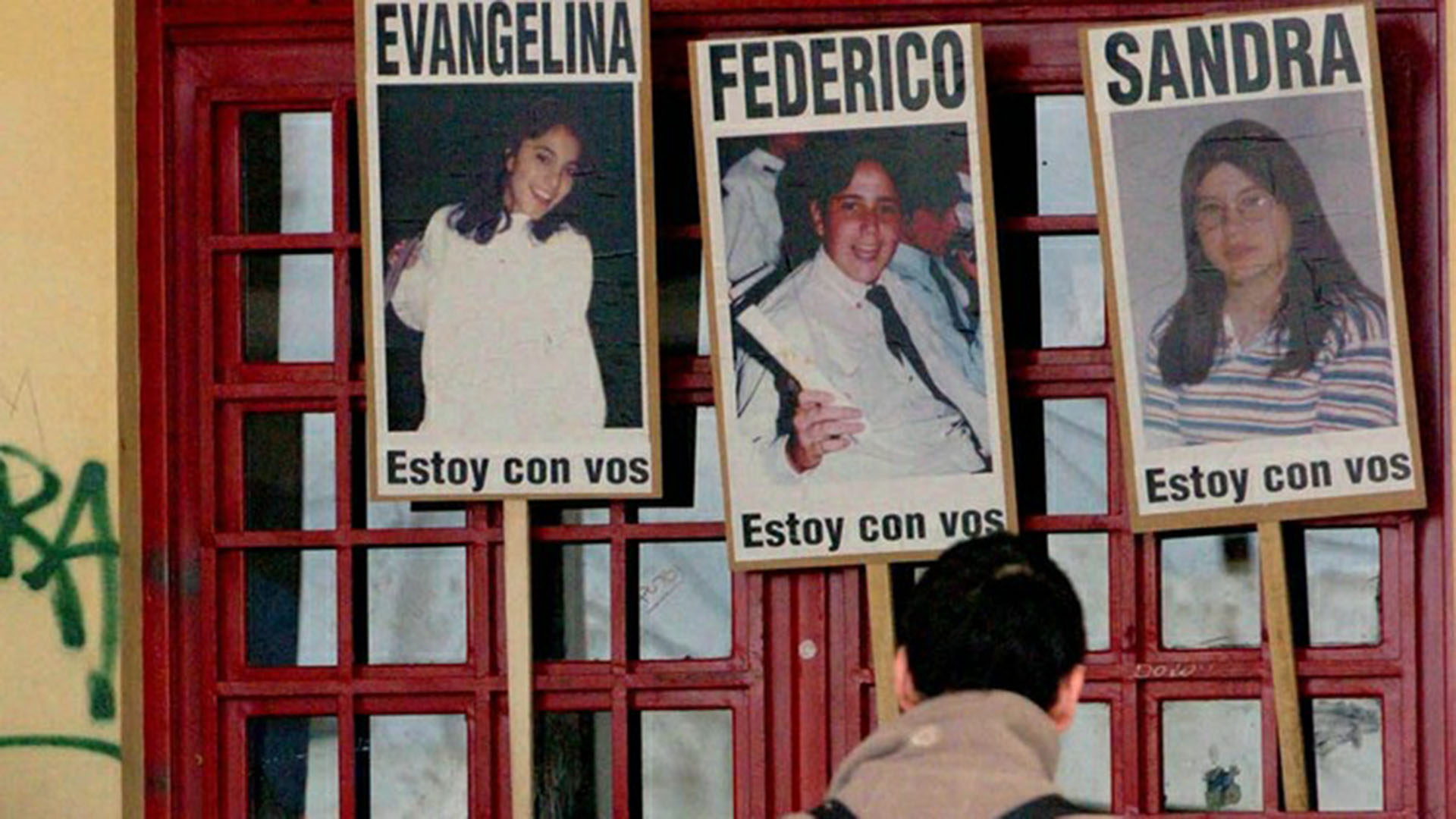

Alejandro Castro Santander, Mendoza educator and writer, general director of the Observatory of School Coexistence (Universidad Católica de Cuyo) and one of the undisputed references in the region on the subject of school violence, who studies from the paradigmatic school massacre that provoked at the time student Rafael Juniors Solich, on September 28, 2004, who shot and killed three classmates of the same class from the Islas Malvinas Middle School, in Carmen de Patagones, Buenos Aires province.

Since then, Castro Santander has not stopped “evangelizing” about the importance of installing and complicating the issue of bullying and school climate as a central point in the educational task. The work for the expert was titanic because, not only did he have to make it visible, but to discuss the complexity of the topic inside and outside the school. Everyone knew about the existence and depth of the subject, but few were concerned with problematizing it and less dealing with it.

According to the latest report by the Argentinian Observatory for Education, which was authored by Castro Santander, in Argentina — as in other countries participating in the tests of the International Program for Student Assessment (PISA), carried out by the OECD (Organization for Education) Cooperation and Economic Development) — students who suffer bullying perform less on learning tests. In other words, bullying among schoolchildren is definitely a serious problem for achieving a good school climate.

This report aimed to account for the relationship between bullying and performance in learning tests, supported by data from the PISA 2018 tests, in which 15-year-old students from more than 60 countries participated. It should be remembered that the PISA tests are an assessment that OECD member countries take every three years globally, and that measures the academic performance of students in mathematics, science and reading.

In a dialogue with Infobae Castro Santander explained, “one of the internal factors that most influences the quality of educational processes is the school climate and paradoxically the one that is least managed within the educational communities. Today, bullying and cyberbullying must be recognized as those forms of violence among students that most hinder the proper development of the school climate.”

This type of harassment, conflicts, indisciplines, and sporadic violence are at the root of bullying or bullying and require proper management of coexistence within educational institutions. The report by Argentinos por la Educación delves into three points and indicators - key to demonstrating the overlap that exists between school climate and quality of learning:

1- School membership

At this point, in order to study the relationship between peer bullying and learning outcomes, measured according to PISA, three indicators were considered: social violence measured through the feeling of lack of school belonging or exclusion; bullying measured through physical violence suffered by students and verbal abuse, measured by the frequency of verbal aggression (e.g. circulating harmful rumors) by students.

2- Physical harassment

This indicator is bullying measured through physical violence suffered by students. This indicator is constructed based on the students' response to the frequency with which they have been beaten or pushed by peers in the last 12 months.

3- Verbal mistreated

This indicator is measured by the circulation of rumors suffered by students and based on the students' response to the frequency with which peers have circulated harmful rumors about them in the last 12 months. The report showed that students who suffered the most bullying perform, on average, on standardized tests (in this case PISA 2018). And this is observed both in the countries that make up the OECD and in the education systems of Latin America.

— With the first lockdown and the validity of virtual education throughout 2020 and 2021, do you think that new forms or formats of school violence appeared?

—Alejandro Castro Santander: Preventive confinement in 2020 and virtual education, first general for those who could, then bimodal but still with many difficulties in connectivity, adaptation of devices, teaching gaps, together with the need for adequate management for each moment of the evolution of the pandemic, were ended up postponing the mental health of all and the safety of students. The dangers in the Network of Networks were already before the arrival of the virus and now, in the face of a longer time in front of screens, the risk, without hesitation, is greater.

In this complex context, new forms of violence did not necessarily appear, but rather indirect forms, such as sporadic school cyberviolence and cyberbullying in particular, increased.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, very specific studies have been carried out in some universities, trying to diagnose, first, the loss of learning and later “teacher well-being”, but there are few studies on what happened to violence in the context of institutions educational. The question that we have to answer is: What happened to the coexistence of students during 2020/21 and how do we plan to work the (re) meeting in maximum presence this 2022?

A Spanish study by the ANAR Foundation and the Fundación Mutua de Madrid on bullying is in advance. Based on data obtained from workshops in more than 300 schools in different regions, it was concluded that cyberbullying was the most frequent form of violence and that WhatsApp was used in more than half of the cases, followed by Instagram, TikTok and online video games.

Students have already insisted on previous studies, that almost half of the cases of bullying remain unsolved, so it is easy to deduce that in the face of the anonymity that cyberbullying allows, impunity is much greater.

We are facing a peak of child and/or school cyberbullying and/or cyberbullying. In these pandemic times, violence in general and harassment in particular adapted by using what they have at their disposal to quickly reach each other: cell phones, computers, tablets...

If many children were already navigating cyberspace alone and with little control, in the pandemic they have remained alone longer. We know how easy it is to switch from use to abuse and the concrete dangers, not only by those who harass their peers, but also by adults who continually seek victims, as in the case of grooming.

How is school violence handled and managed today? It is true that they are more settled in the social debate, but have the figures improved?

— In Latin America we took longer to talk about bullying, a phenomenon of violence among schoolchildren that has, since research, been around 50 years old. In Argentina it was our sad case of Carmen de Patagones, who timidly started us in the work on this type of harassment. Almost 18 years passed and we still have not given concrete answers, not only to harassment, but to conflicts, indisciplines, sporadic violence, and of course to the emerging one due to their neglect: bullying.

We talk more about bullying, sometimes misusing the term, but it is true that it is incorporated into social debate. Unfortunately, those who manage education call action “prevention” when it has already happened, when we have aggressors, victims and a large number of justifications, including: “we already applied the protocol”. The challenge remains that of knowing the social “temperatures” in order to have early warnings, to prevent through actions at different levels (school, family, school environment, etc.). Violence is always vigilant, does not rest and only needs to be neglected. Therefore, innovation attacks and then a long nap are useless.

Review by the numbers

—Castro Santander: From the Observatory of School Coexistence (UCC), our diagnostic approaches to the phenomenon of violence among schoolchildren have indicated to us in the last 15 years that between 20 and 25% of students are afraid of a colleague. And that the most common forms of abuse, especially in puberty and adolescence, are the indirect ones: breaking, hiding and stealing belongings from one's partner; murmuring, slandering; excluding from regular coexistence activities at school or not letting participate in extracurricular group activities.

Very sad, because it breaks the belonging to the group of equals, something that for many is more important than being well in studies. Thus, the social climate, school coexistence, becomes the factor associated with student achievement and the most significant educational quality.

It worries the idea that as they get older, to the question Who do you communicate to when you suffer the mistreatment of a partner? the adult is disappearing. It becomes clear that they do not see us, both teachers and parents, as references capable of helping them in the face of their difficulties of coexistence. We have been losing the habituality of dialogue with them. In 2019, in its “Behind the Numbers” report, UNESCO reported that almost 1 in 3 students have been mistreated by their peers “at least once in the last month.”

— How do you see the future of school violence, throughout your more than 25 years of academic-professional work, at the beginning in solitude and today with the most installed theme?

“If I stop at the actions that have been carried out through public policies, I see no intention of changing the situation with regard to violence in schools. It is easy to argue that responsibility lies with the aggressor's family, or there are overprotective parents or the school was not attentive.

Sporadic and almost always reactive actions (laws, resolutions, protocols) have been observed in the last 15 to 18 years. When something happens that shocks public opinion, a “saving” response appears that will solve the old problem. Result: when we intend to launch foreign programs, by not consulting local experts who expect to be heard in universities, as there is no comprehensive program to accompany the proposal (awareness and training for managers, teachers, families, supervisors and the students who are the protagonists) most important prevention and intervention) the prognosis will not be good. We're filling schools with smoke.

Let us remember that we are talking about violence, voluntary harm, and that sometimes we can also encounter situations that may involve mental health problems and crimes, for which the educational community is not prepared.

However, in the face of the ineffectiveness of many school governments or legislation that only tickle violence, I trust the judgment of many managers and teachers who, knowing their schools, their students, can apply multilevel actions to their institutional project that have an impact on the coexistence of everyone and can say that for them good coexistence, conviviality is a priority.

We have learned a lot in these almost 50 years of studying and living with bullying, so that it remains a silent protagonist in the lives of many students. You can't study with fear. You can't grow well with fear. We adults have a great responsibility for our children/students to learn in better climates of coexistence. And this is true today for schools as well as universities, for boys and girls and for teachers, who may also experience situations of workplace harassment from managers or colleagues.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs