In the context of the great geopolitical rivalry that the United States and China have been having for years, and which even led to a trade war between the two powers, the Asian giant took advantage of the weakness of a region such as Latin America to extend its global influence and confront US competition.

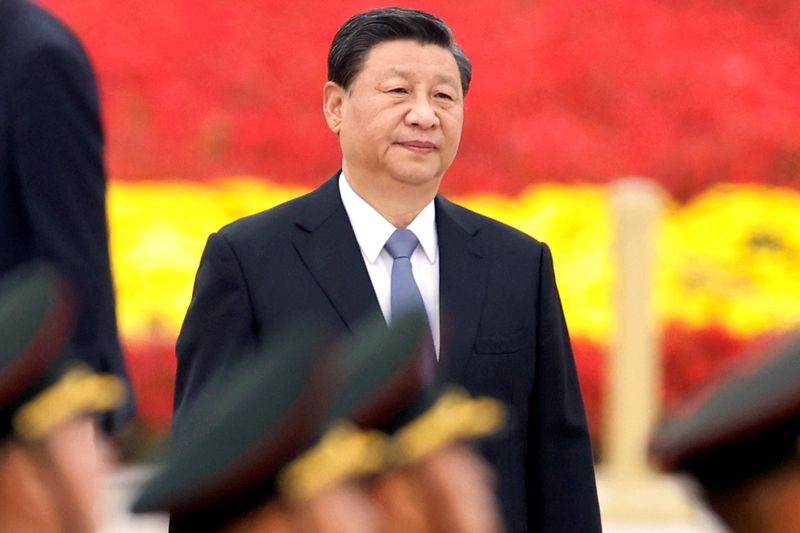

As part of a virtual forum organized by the FAES Foundation, Jorge Sahd, director of the Center for International Studies of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile and a specialist in matters related to China, explained the risks of this growing influence of the Xi Jinping regime in Latin America and warned about the “trap of Chinese debt”.

According to projections from 2014 to 2023, the analyst indicated that Beijing found itself with a hemisphere that is on its way “to a new lost decade, such as the 80s”. The average growth in the last ten years is less than 1%, having had a significant stagnation since 2016, which led the region to end 2019 as the least growing continent in the world.

“The fall in investment, the difficulties in Latin America's economic recovery, the possibility of approaching a lost new decade, are clearly opportunities for China because countries need foreign investment and financing,” he explained.

Faced with this scenario, and with the dwindling US presence, China took advantage of the situation. In a short time, the amount of loans granted to Latin American countries increased exponentially. The peak was seen in 2010, above $35 billion; and although there was a slight drop in subsequent years, that close dependency relationship still persists.

Countries such as Venezuela (17 loans/$62.2 billion), Brazil (12 loans/$29.7 billion), Ecuador (15 loans/$18.4 billion), and Argentina (12 loans/$17.1 billion), are at the top of this ranking.

Foreign direct investment is also growing and diversifying. “Through the Belt and Silk Road, China approaches different countries. Nowadays, almost 140 countries in the world have some form of support to this initiative. The accessions range from formal incorporation, from concrete projects, even with funding, to the signing of what is called a memorandum of understanding. In Latin America and the Caribbean there are already 20 countries that have signed a memorandum of understanding, with different levels of intensity with China,” said Sahd.

Countries where foreign direct investment from China has been growing: Brazil (60,000 M USD), Peru (27,000 M USD), Mexico, Argentina (12,000 M USD). In Argentina, President Fernández's visit to China in February had a political controversy, where he went with a list of 17 Argentine projects that require investment and financing.

Traditionally, Chinese foreign investment was oriented towards the extractive sector. But today it is mainly concentrated in the energy sector, metals (especially in the mining sector), but also in the agricultural, chemical, finance and logistics sectors.

The specialist acknowledged, however, that Chinese investments “have not been without controversy”. In this regard, he recalled the problems with the dams that began in Santa Cruz, Argentina, due to environmental standards. That project, in fact, came to a standstill. There were also similar situations in mining cases in Peru and Ecuador, “where there has also been opposition from the communities”.

Sahd also referred to investment in Chilean passports. A Chinese-German consortium won the tender for these documents, with a very attractive economic offer. “But the United States knocked on the door and said there were risks in terms of processing personal data. A few months ago, this rivalry knocked on Chile's doors, as it has touched it in many Latin American countries, which have so far built their development on the basis of accepting foreign investment, principles of non-discrimination, because, unlike countries of the European Union, we do not have built-in elements of national security. in certain strategic investments”.

Chinese influence increased even more since the start of the covid-19 pandemic, which, paradoxically, originated in that country. The Chilean analyst stressed that Xi Jinping's regime deployed what was called the diplomacy of “masks and vaccines”, through which it provided supplies, medical and immunizing materials to countries in the region. Such was the penetration of the Asian giant, that more than half of the vaccine supply came from Chinese laboratories. This, as far as “vaccines sold, not donated” are concerned.

Against this background, Sahd warned about the risks of generating a debt commitment to the Chinese regime, and referred as a result of this, the so-called “Chinese debt trap”. In his view, this situation may have effects from the geopolitical point of view and from the dependence point of view for countries.

“All these elements are not yet strong in the public debate in Latin America, as is the case in other parts of the world,” he said.

Despite his growing influence both in Latin America and globally, the Chilean specialist stressed that “China does not currently enjoy high levels of trust worldwide.” Above all, after his handling of the pandemic.

This negative image predominates in the United States, Canada and the European Union. But, according to Sahd, in Latin America “there is an emerging awareness of the risks posed by China.” Although, he added, the current position of the region is practically one of neutrality in the face of the confrontation between Washington and Beijing: “Latin America's position has been 'I want the best of both worlds, I want to benefit from China's trade and even investment opportunities, but I want to maintain the historical relationship of values , the promotion of democracy, the human rights promoted by the United States. '”

In a context of growing strategic rivalry, “the question is how far can our region maintain that neutrality.” And along these lines, the Chilean expert considered that Latin American governments “must adjust their foreign policy according to the new reality.”

Sahd even mentioned among the political risks linked to Chinese influence “regional irrelevance”. As he pointed out, Latin America has lost strategic relevance to global decisions in recent years, “due to the lack of vision, cooperation and integration among countries”: “This causes the region to lose its voice, a specific weight in major global debates.”

Regarding future relations between the United States and China, he said that, while it was presumed that there could be a closer rapprochement with Joe Biden following the very bad relations under Donald Trump's administration, “the rhetoric may change, but the direction of the conflict continues and will deepen.”

At the end of the forum, Sahd was consulted about a possible mediation by China in the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. In this regard, he stressed that one of the things that has hindered negotiations between the parties, “apart from the fact that Russia wants to continue strengthening its negotiating power, which is why it practically continues to encircle Ukraine and Kiev, is that there is no mediator.”

However, he said that China “also represents a challenge, or a risk, for the United States”: “China, more than allies, has customers or debtors. What it seeks is to try to defuse any risk of greater regional instability (...) I find it difficult for the United States to accept him as a mediator,” he concluded.

Keep reading:

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies