A few weeks ago, the international photojournalistic scene witnessed, with some perplexity, a new photographic controversy.

The Norwegian reporter Jonas Bendiksen published his photobook The Book of Veles, which was also presented at the prestigious Visa pour l'image event, held annually in the French town of Perpignan and which is embodied as one of the most relevant international photojournalistic meetings of today. So far, everything is more or less normal.

But, shortly thereafter, the Magnum agency (to which Bendiksen belongs) made public that, although The Book of Veles illustrated a real event, almost everything contained there was false: the photographs had been taken with virtual actors, the texts were invented and, in short, we were dealing with a photographic experiment (one more) that reflected on the lax processes of verification of the photographic image in journalistic contexts.

Welcome to fake news

Things take on a special note when the conceptual rudiments of this publication are known: Veles is a city in Macedonia, the cradle of numerous false news during the US presidential campaign in 2016. In this remote enclave (if we think about it from the point of view of the United States) countless websites would have been created that published false information, later virilized on social networks, in favor of Donald Trump.

Bendiksen photographed different places in Veles in 2019 and 2020 without its protagonists — since these websites no longer existed. Later he created avatars that he included in his images, giving an invented life to those empty places. He completed the proposal with an essay also generated automatically by computer software.

Although when we talk about these types of projects that play with the truth, we run the risk that some of the issues that we have described so far will be qualified or amended, we will assume that what Bendiksen created in The Book of Veles is a fictitious story about a true event. A “photographic mockumentary” that has allowed him to reflect on the way in which information is produced and consumed. A debate that, on the other hand, perfectly dialogues with many of the problems of our media culture and, also, with the current agenda of academic interests or fashions.

This is not new, at all, and there are other well-known examples that, as if it were a genre, explore (some with more success and others with less) the complex relationships between photography and reality.

Those “other cases” that make us think

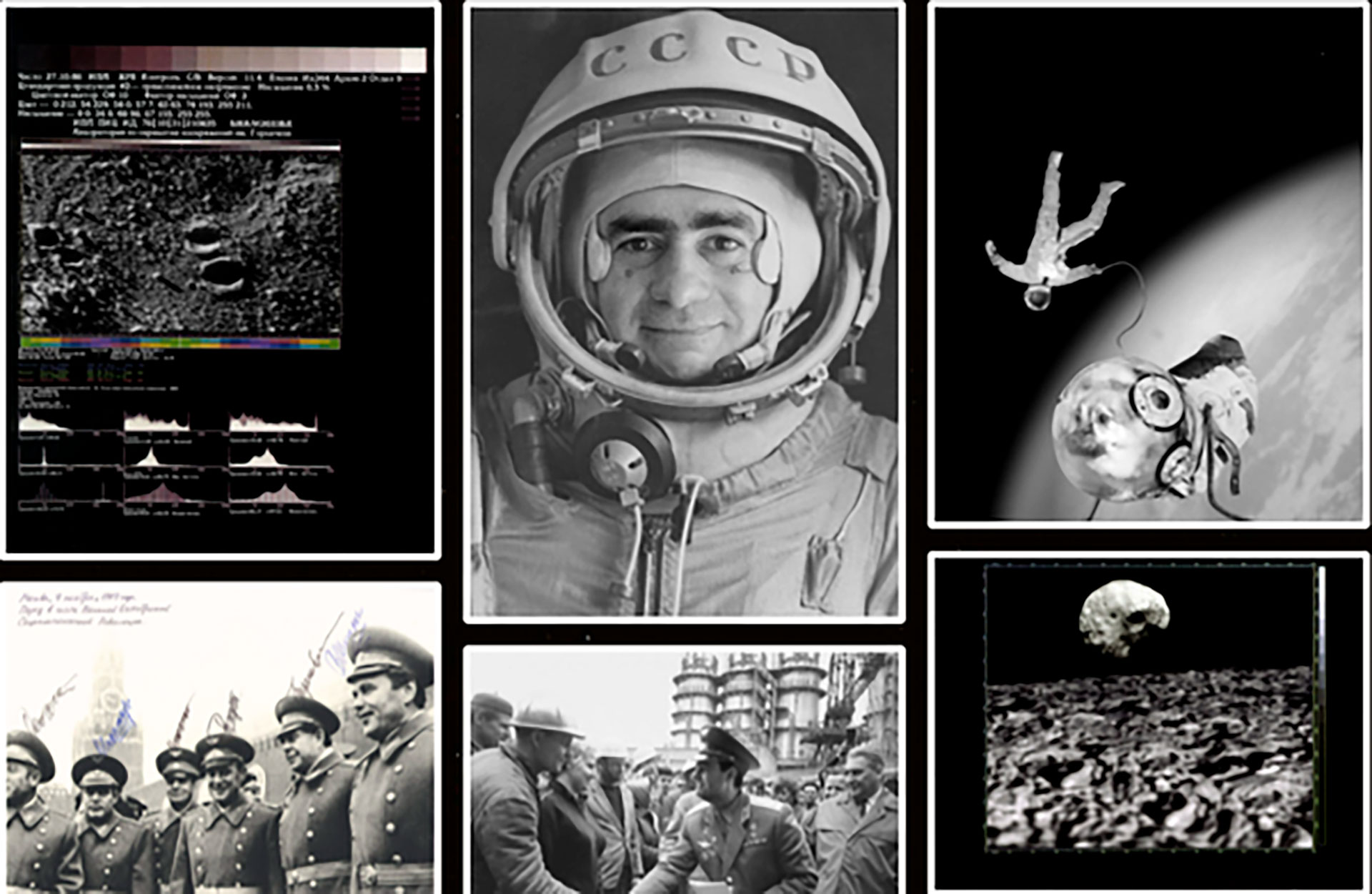

Joan Fontcuberta's work is well known. An essayist, curator, historian of photography, conceptual artist, critic, teacher and mainly photographer, Fontcuberta has been working on very hard graphic projects for decades that help us better understand the strategies of meaning that images hold. Sputnik, Wildlife, Herbarium, Ximo Berenguer or Trepat are some of his creations.

Using photography as the subject of priority expression, all these projects stage our convictions about the image, while subverting notions of truth and lies so that we reflect on the iconic manipulation we are subjected to today.

Something similar could be seen in the 2009 Paris Match award-winning work by Rémi Hubert and Guillaume Chauvin.

For the occasion, both photographers orchestrated a production in which they combined features typical of the most traditional documentary and photojournalistic photography (black-and-white reportage, certain sweeps apparently the result of dynamic photography...) with the intention of documenting a problem: students who have to play very precarious jobs to afford their university education. But it was all a setup. These examples do not say that photography cannot reflect reality, but rather state that the media, or some institutions, make spurious use of the power of credibility that we give them. They use their courage to tell us lies. Or half truths...

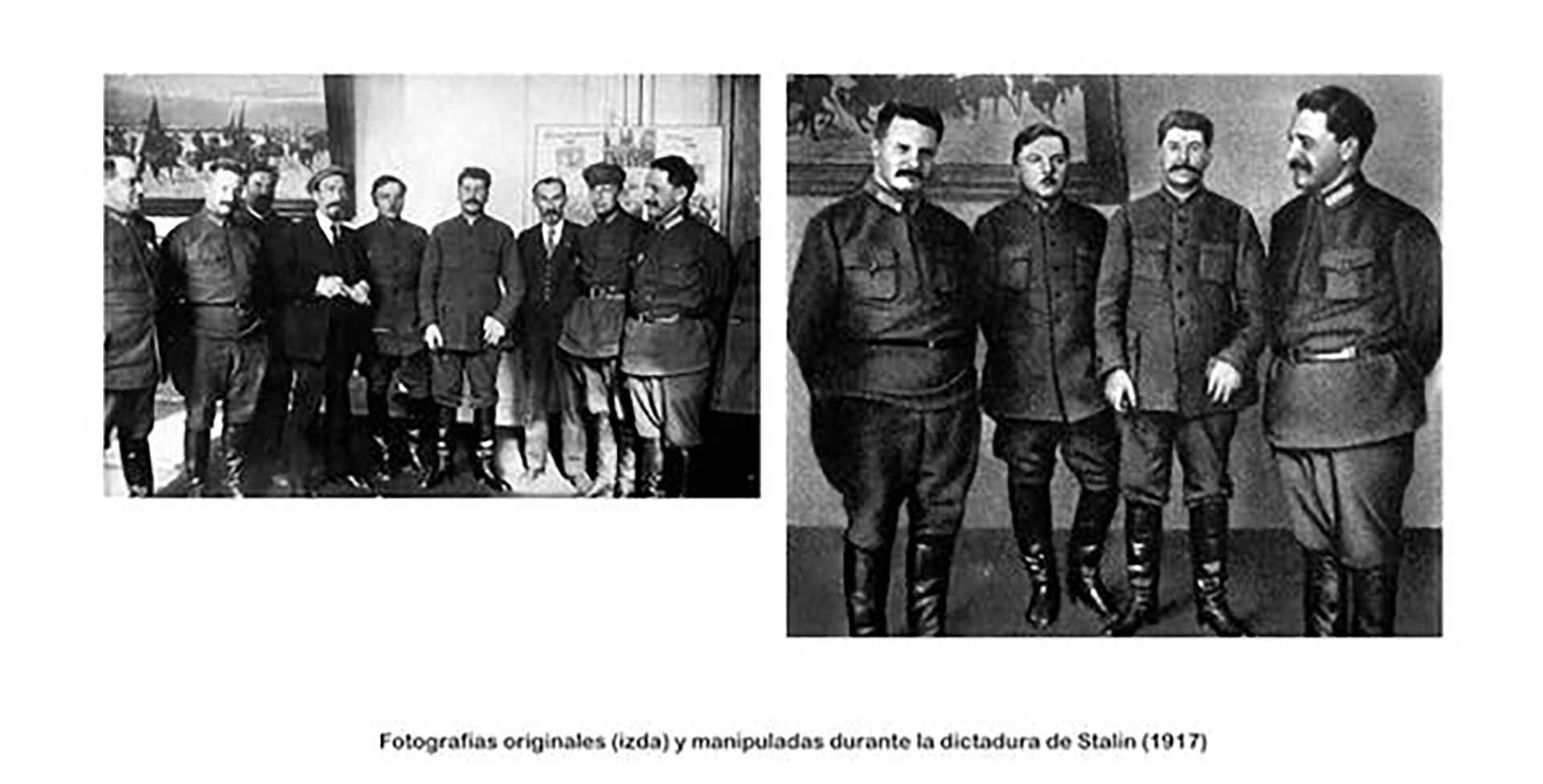

Different cases are those photographic manipulations that do not intend to arouse any consciousness, but, on the contrary, seek to distort the information in order to obtain some kind of profit. Induction to interested error usually occurs either to publish the image and obtain an economic benefit, or to carry out an informative manipulation and obtain some ideological compensation.

The numerous examples of retouched photographs of politicians, the demonstrations where people present at the event are cloned or deleted, the unfree reframing of scenes to make someone disappear are good examples of this other type of photographic confection.

In this regard, we could highlight the analysis of the so-called Reutersgate by the aforementioned Joan Fontcuberta in his book La camara de pandora. The photograph after photography or the collection of photojournalistic manipulations that Diego and Daniel Caballo collect in Photography without truth. The power of lies.

Both cases confront us with the edges present in the complex relationship between photography and reality, something that comes from afar and has its roots in the very birth of photographic technique.

Photography and reality: intimate enemies

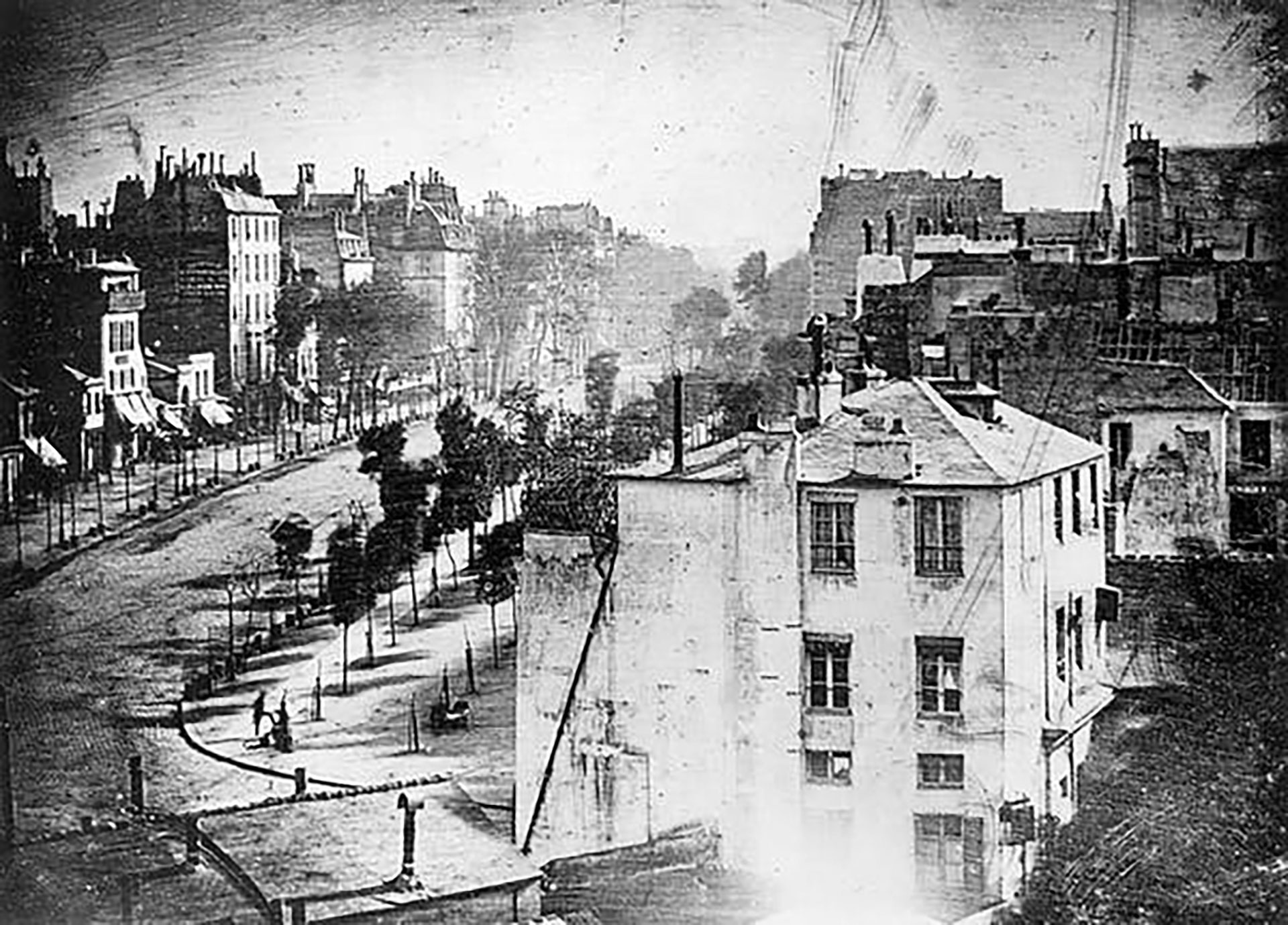

In 1838 Louis Daguerre took the photograph entitled Views of the Boulevard du Temple. The image portrays what should be a busy Parisian street, but strangely enough we only observe the presence of a man who lifts his leg.

The mystery is not such: the exposure times required to obtain a photograph in those early years of the invention were very long. That's why whoever moved didn't appear in the picture. And on that popular street in Paris everything moved except the person who was patiently detained, cleaned his boots by a shoeshine (and who, it is believed, was conveniently warned and placed by Daguerre). One of the first photographs in history that we know of does not faithfully portray what was really happening at that time and in that place. Here, the photo doesn't tell us “this is this, it's like that, it's just like it”, paraphrasing Barthes. Rather here, and due to the technical precariousness of the moment, the photo is an image that testifies little to what happened.

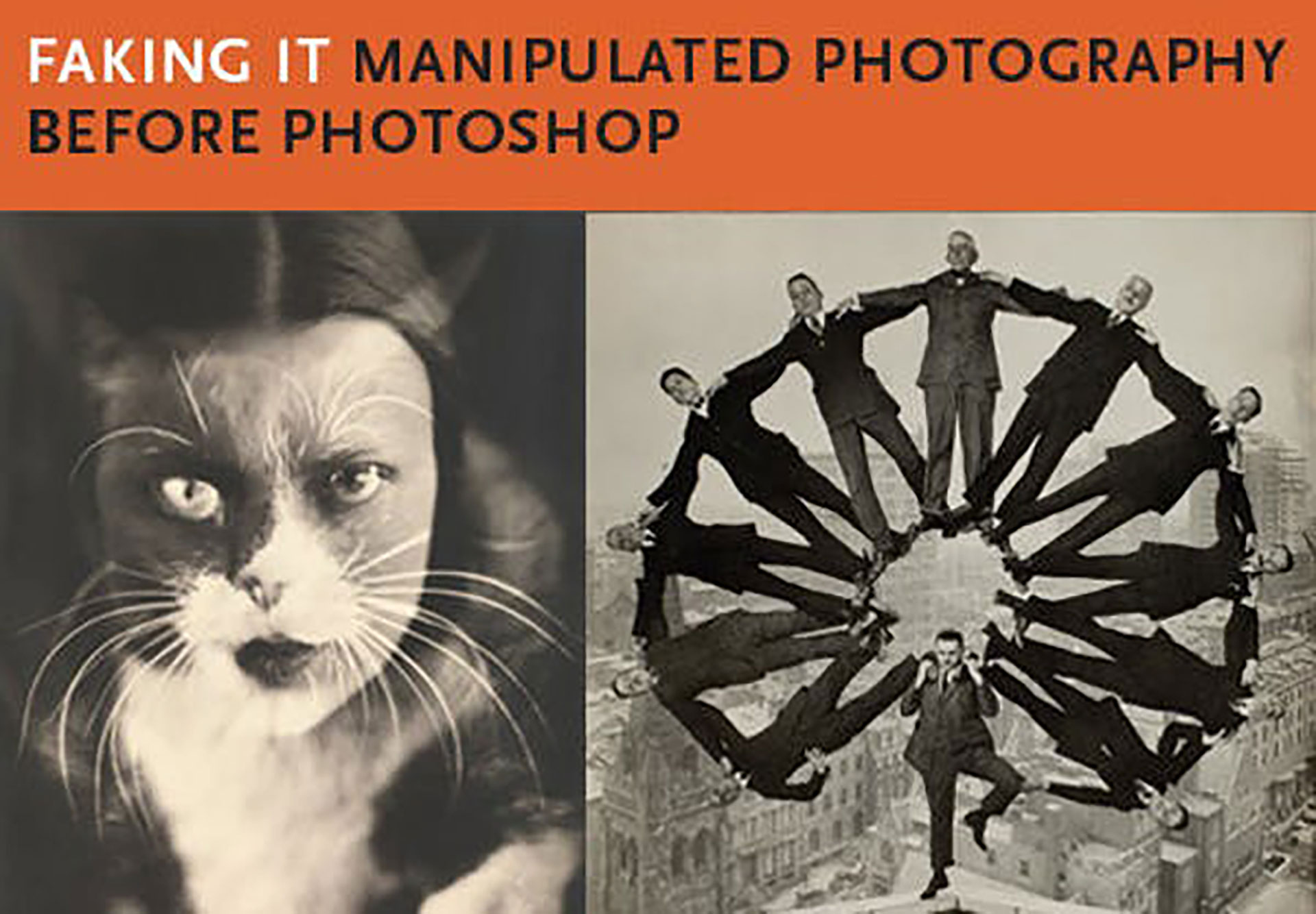

We might think that once these limitations were overcome, some time later, we would already enjoy the benefits of an invention that gave us exact copies of the real, but the truth is that the photographic image's ability to shape the world has always existed, been known and used for numerous purposes (artistic, political, economic...). Proof of this is the exhibition Faking it: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop held at the Met Museum in New York in 2013, which, precisely, showed how before digital imaging photography was a very useful tool for this type of experiment and photographic forgeries.

So can we never trust a photographic image? Of course we can. We can do it to the same extent that we rely on a news story, a history book or a film documentary.

Photography has given us great doses of iconic realism and is, without a doubt, a tool that offers us the possibility of reflecting (with the suggested restrictions) what happened. Currently, the use of photographs makes it possible, without going any further, to certify our identity in many official documents. That is, it still enjoys an incalculable authentication value. But that does not mean that we do not assume that it is a discursive construction that needs its context of use to be understood. And that it has as many options as there are limitations when it comes to portraying the world around us.

In fact, we can conclude this photographic debate with the following phrase written, more than ten years ago, by Santos Zunzunegui: “The most important thing would be on the side of ending, once and for all, the faith that we have placed in the image as a replica of the world to see it not as what is an emanation of a reference (in traditional discourse on analogue devices) but as a privileged mechanism of production of reality, that is, of meaning”.

*Nieves Limón Serrano is teaching and research staff at the Faculty of Communication of the University of Castilla-La Mancha.

Originally published in The Conversation.

KEEP READING

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

Members of the Specialized Prosecutor's Office in Nuevo León secured the Nueva Castilla Motel as part of the investigations into the case

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Kane Tanaka lived in Japan. She was born six months earlier than George Orwell, the same year that the Wright brothers first flew, and Marie Curie became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The body was left in the back seats of the car. It was covered with black bags and tied with industrial tape

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

The top Mexican football champion will play a match with Pep Guardiola's squad in the Lone Star Cup

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies

A so-called protection against the spread of diseases threatens the integral development of dogs