(Bloomberg) -- Follow Bloomberg on LINE messenger for all the business news and analysis you need.

In Southeast Asia, migrant workers at the bottom rungs of society have borne the brunt of Covid-19. Without real efforts to address their plight, the group could prove to be a key risk to the region’s ability to shake off the pandemic.

These workers, numbering some 10 million in Southeast Asia, have become the main vectors of recent resurgences of the coronavirus in countries like Malaysia and Thailand, even as they power the industries that produce goods such as rubber gloves and frozen foods that have soared in demand due to the pandemic.

The problem is forcing governments to confront the flaws of the the low-wage labor model that they have for decades relied on, as they come to terms with the fact that an effective long-term public-health solution will have to involve raising the living and working standards of migrant workers.

“Before the Covid era, many employers preferred to employ migrants because it was easier to put them in forced-labor-like conditions,” said Adrian Pereira, executive director at the North South Initiative, a Malaysia-based non-governmental organization focused on social justice.

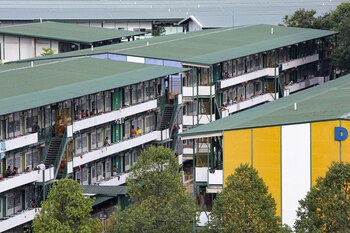

Crowded Dorms

Singapore learned the lessons early in the pandemic. After seemingly containing the virus in the first weeks of the outbreak, authorities were blindsided by a surge in cases in foreign worker dorms that forced them to impose a nationwide lockdown. The island nation has since brought the outbreak under control with strict measures that included movement restrictions for the workers.

In Malaysia, demand for rubber goods required for personal-protective equipment even helped mint a new billionaire, but that surge in economic activity is being tested by a runaway outbreak that has seen daily infections recently exceed 4,000. Earlier this month, the king announced a state of emergency, shortly before a lockdown for most of the country came into effect. Most of Malaysia’s new infections have been linked to migrant workers hailing from countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar and Indonesia.

Authorities are zeroing in overcrowded conditions in worker dormitories that have been a major factor behind the spread of the virus. Of Malaysia’s more than 1.5 million documented migrant workers, 91% live in accommodation that does not meet the country’s minimum housing standards, according to the Ministry of Human Resources.

One of the major sources of infections in the latest outbreak was factories belonging to rubber glove maker Top Glove Corp., whose shares have soared in the past year. After discovering thousands of infections among workers at Top Glove’s plants in November, the government carried out raids on its dormitories. Authorities are also seeking charges against glove maker Brightway Holdings Sdn. for alleged offenses under various housing standards laws. Top Glove reported at least 305 new Covid-19 cases in the past week.

Malaysian employers must now also provide quarantine centers for migrant staff infected with the coronavirus, Human Resources Minister M Saravanan said earlier this month. They must also pay for medical and living costs, including vaccinations, throughout the quarantine period, he said.

Porous Borders

Those measures, however, cover only documented workers. As Singapore’s success shows, having an strongly enforced border is crucial to tackling the massive problem of illegal migration across Southeast Asia’s porous frontiers.

“If you look at the countries that have been most successful at keeping numbers down so far it’s New Zealand, Australia, Singapore and Taiwan -- one factor they’ve got in common is that they can control the borders more for outside people coming in,” said Peter Collignon, an infectious disease physician and professor at the Australian National University.

Malaysian authorities last year conducted raids on foreign-worker enclaves targeting illegal migrants in the midst of a lockdown, detaining hundreds of people in the process, drawing scrutiny from rights groups. There are believed to be some 2 to 4 million undocumented workers in Malaysia, according to the International Organization for Migration, a United Nations agency.

In Thailand, the total number of Covid-19 cases remains relatively low at just over 13,000. However, migrant workers have become the main source of a recent wave of infections and make up about a quarter of all infections in the country, according to Health Ministry data.

Some of the estimated 4 to 5 million migrant workers in Thailand are afforded social protections, but those working in markets or farms and living in cramped shared rooms are at greater risk of contracting the virus.

“Migrant workers in the area live in crowded apartments, with about six people sharing a three-by-six room where they take turns using the room based on their morning or night shifts,” said Adisorn Keadmongkol, a coordinator at NGO Migrant Working Group Thailand.

Without stronger border controls, however, it will be difficult for Thailand to quickly quash the latest outbreak. Poj Aramwattananont, vice chairman of the Thai Chamber of Commerce, said that a growing number of citizens from neighboring Myanmar are crossing the 1,500-mile border to find work in the informal sector due to spiraling unemployment at home and tougher employment rules in Thailand that make finding legal work harder.

Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-Ocha, who blamed the latest outbreak on the employment of illegal migrants, has vowed to crack down on the practice of employing undocumented workers. His government has ordered police to probe and arrest anyone engaged in smuggling workers. Barbed wire fencing had also been erected around a seafood market and migrant community in Samut Sakhon province -- where the latest outbreak originated -- to prevent workers from leaving.

Effective border control will also be key for Southeast Asia’s vaccination drives to succeed.

Collignon at ANU said that a successful vaccination program requires that 80-90% of people are vaccinated. “The trouble is if you have a lot of people going over the border, particularly from poor areas, or from areas where there’s not as good vaccine delivery, then that means that you suddenly haven’t got 90% of people vaccinated and they might be people more likely to have infection.”

Build Back Better

Singapore is an example of an economy that is “building back better,” said Nilim Baruah, senior specialist in migration at the International Labor Organization. “In Singapore, there is recognition from the top down about the contribution that migrant workers make to the economy.”

When daily cases topped a thousand early last year, authorities moved to quarantine dormitory residents, many of whom were confined there for several months with limited exceptions for work. They were then tested and separated into recovery facilities or cleared dorms and allowed to gradually go back to work with stringent check-in and testing procedures over months. The number of dormitory cases has since fallen to near zero. Serology testing showed that nearly half of the 323,000 workers living in dormitories in Singapore were at one stage infected.

In the longer term, Singapore in June committed to improving living standards and building new dormitories that ensure more space, lower occupancy and better ventilation. Malaysia too has committed to raising living standards, Baruah said. Many migrant workers in Thailand that are registered are meanwhile already offered unemployment insurance while authorities actively work to regularize undocumented workers.

Without a wholesale change in attitudes toward marginalized communities, however, Southeast Asian countries are unlikely to be able to fully get the pandemic under control and protect themselves against future outbreaks, said Leong Hoe Nam, an infectious disease specialist at Singapore’s Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital.

“The virus sniffs out the weakness in all cities and populations, and proliferates well in them,” Leong said.

Últimas Noticias

Debanhi Escobar: they secured the motel where she was found lifeless in a cistern

The oldest person in the world died at the age of 119

Macabre find in CDMX: they left a body bagged and tied in a taxi

The eagles of America will face Manchester City in a duel of legends. Here are the details

Why is it good to bring dogs out to know the world when they are puppies